Doing a graduate degree can be an intense experience. You spend a lot of time with your grad school cohort: you share the ups and downs of grad student life, the ins and outs of dealing with your supervisor, and the unknowns of navigating the research world.

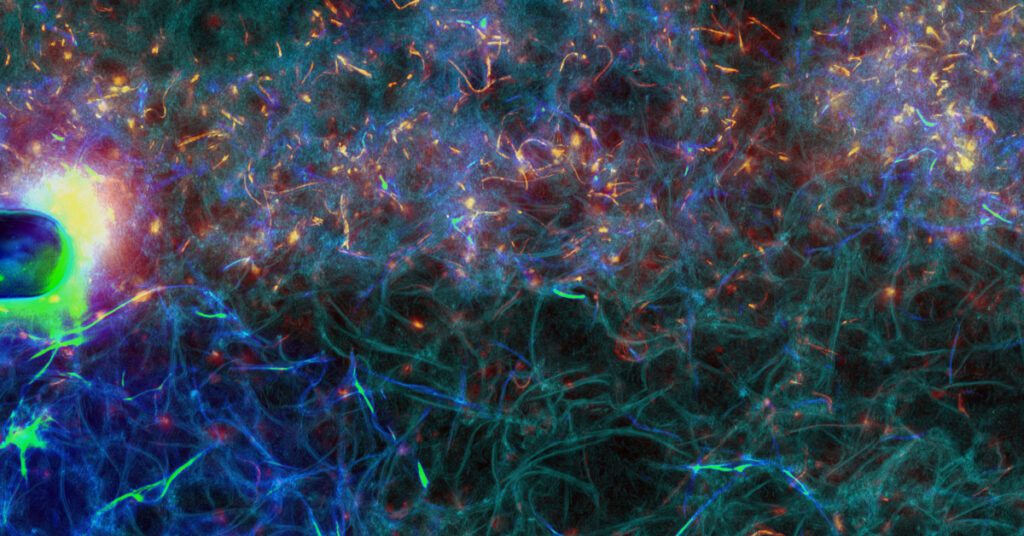

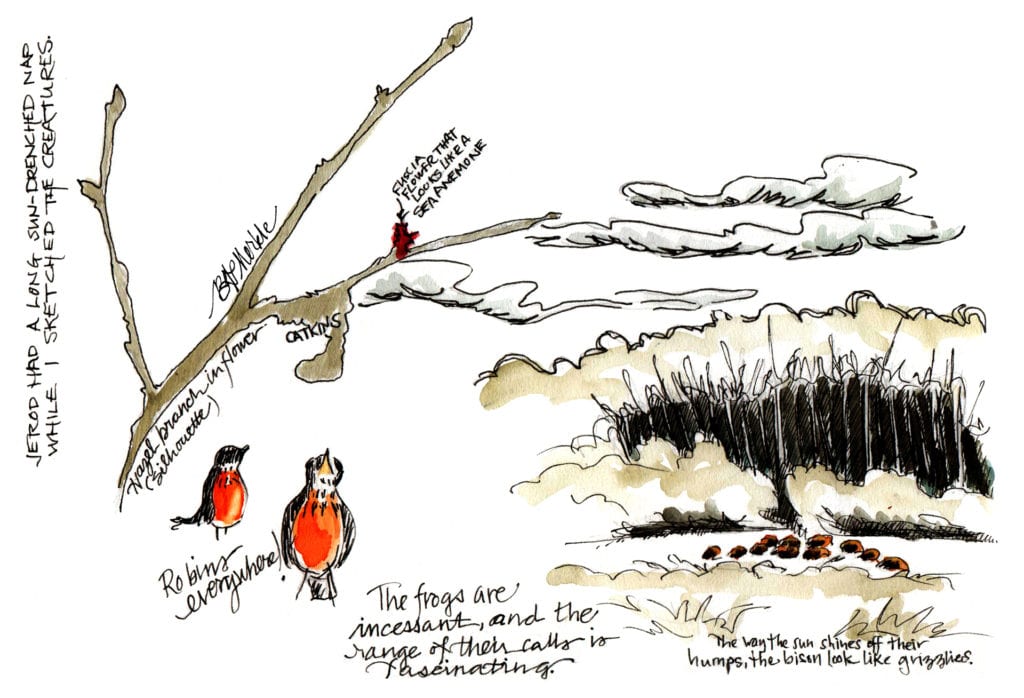

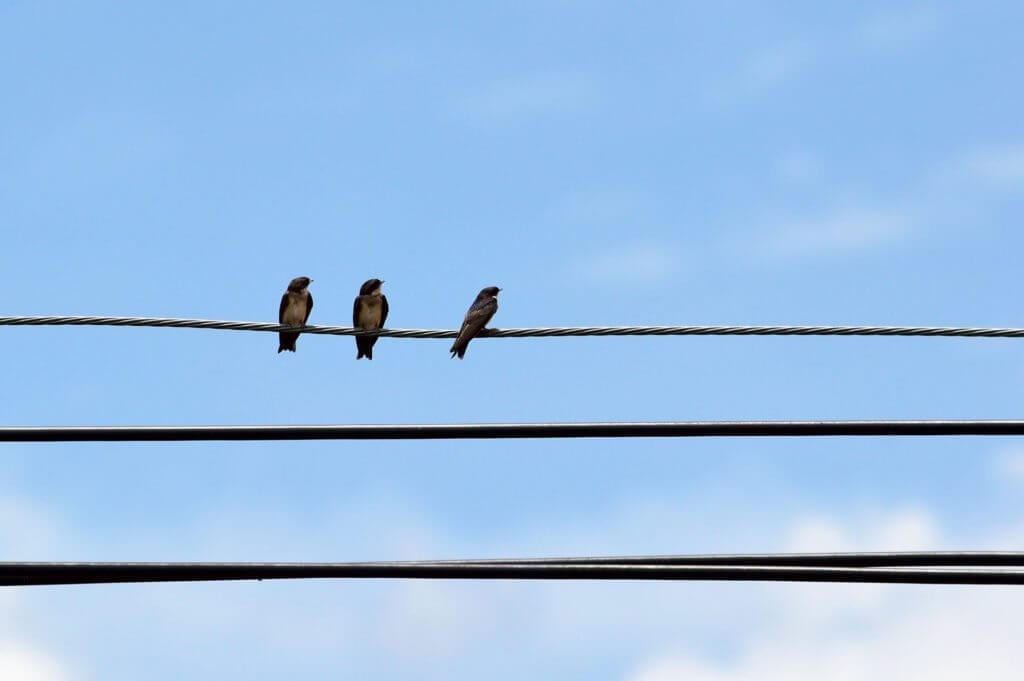

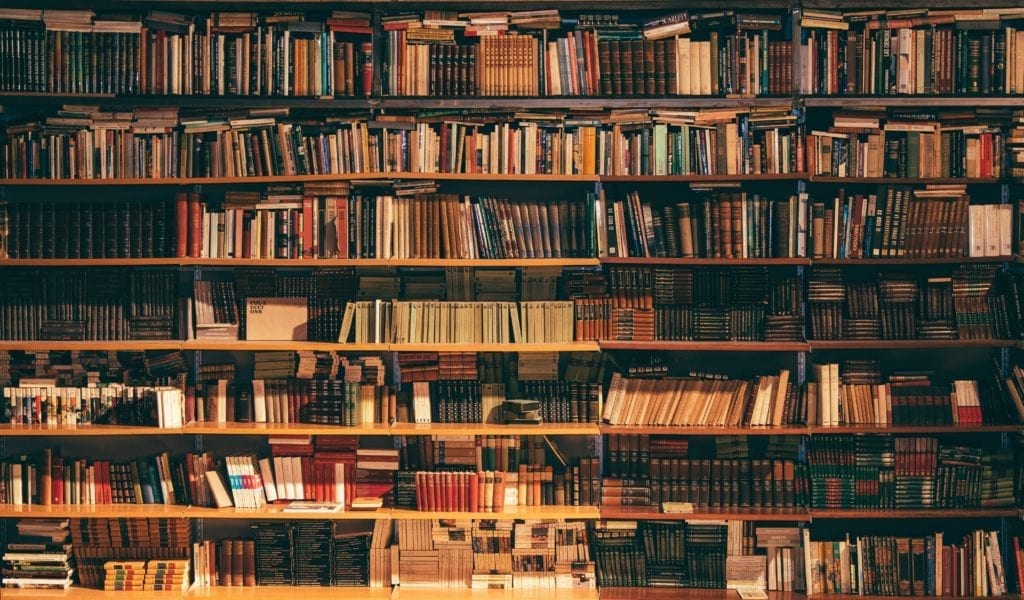

These connections form the beginnings of a scientific family tree (or academic genealogy, as it’s more accurately termed), based on mentoring relationships rather than traditional family roles. Picture it: your supervisor as the ‘parent’, and your cohort as your ‘siblings.’ Your supervisor’s cohort as your ‘aunts’ and ‘uncles,’ and your supervisor’s supervisor as a ‘grandparent.’ And so on.

It’s not as odd an idea as you may think, and conceptualizing your academic genealogy this way can actually offer some advantages when it comes to your scientific career. For one, keeping in touch with your ‘family’ can be a relatively straightforward way to network. But perhaps more importantly, being aware of your scientific heritage gives you a broader perspective on your own research project and a potential sense of direction if you start your own research group.

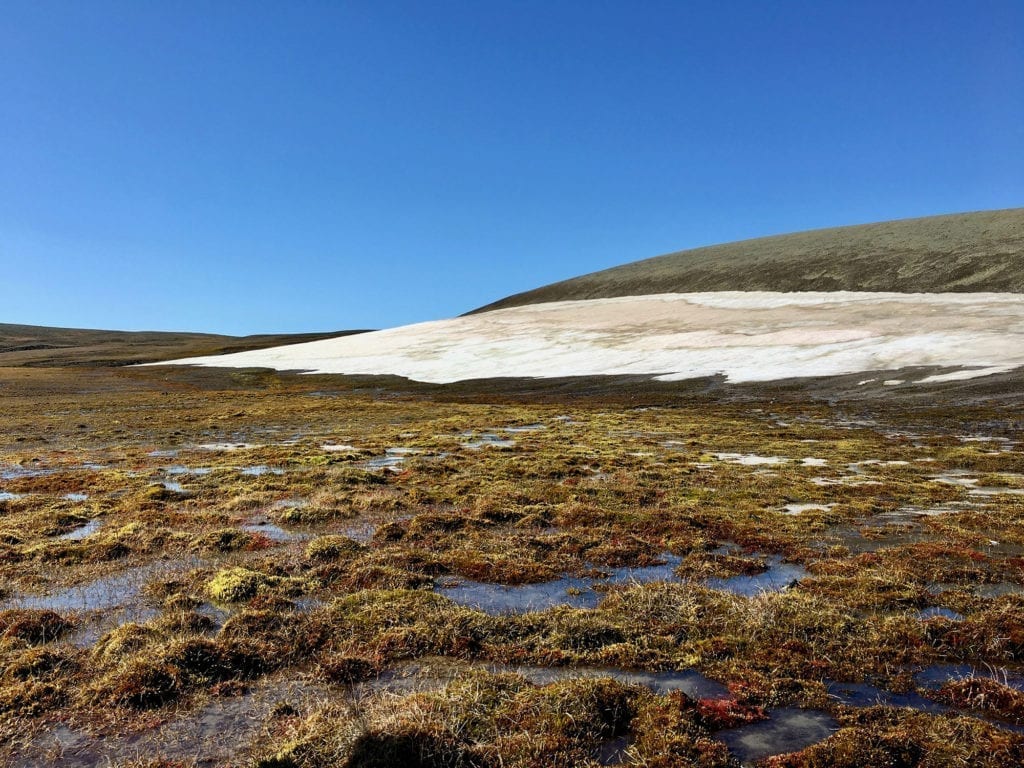

Canada has several research ‘families’ that originate from key initial scientists. Permafrost researchers from J. Ross Mckay’s lab at the University of British Columbia, for example, or hydrologists from D.M. Gray’s lab at the University of Saskatchewan. For better or for worse, it’s these ‘families’ that knit research communities together. It’s not unusual to go to a Canadian science conference and find four to five ‘generations’ of researchers who can trace their lineage back to one of these—or several other—original Canadian scientists.

It can be difficult to find your family, however, particularly for students doing interdisciplinary research. For example, my PhD combined hydrology, meteorology, and glaciology. Since my direct family was largely focused on glaciology, I often felt that I didn’t quite fit. I still remember the first hydrology student conference at which I presented. The hydrologists likely saw me as the weird relative from overseas who barely spoke their language, while I saw them as a family I’d like to be adopted into. It was my first foray into a research field that I eventually fully adopted, becoming the familiar cousin at the table rather than the odd person out.

Families can be quite helpful for networking, particularly if you are new to a field of study or even studying in a different country. During my PhD, it was difficult to network with Canadian researchers because our supervisor had immigrated to Canada from the UK, so our research family tree was largely UK- rather than Canada-based. But if you look at our tree now, my research ‘siblings’ are spread across the country, each with their own students and research programs, each having made new connections to the Canadian scientific community. Because we have a shared history, it makes it easier to talk with them and to introduce our own students into the Canadian scientific family, of which we’ve become a stronger part.

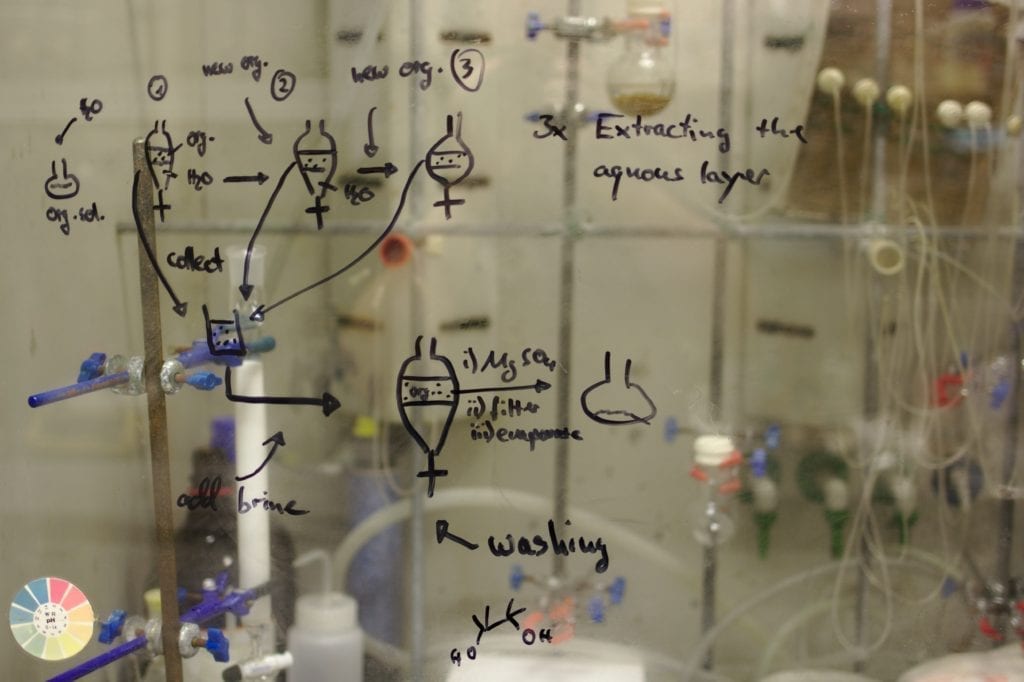

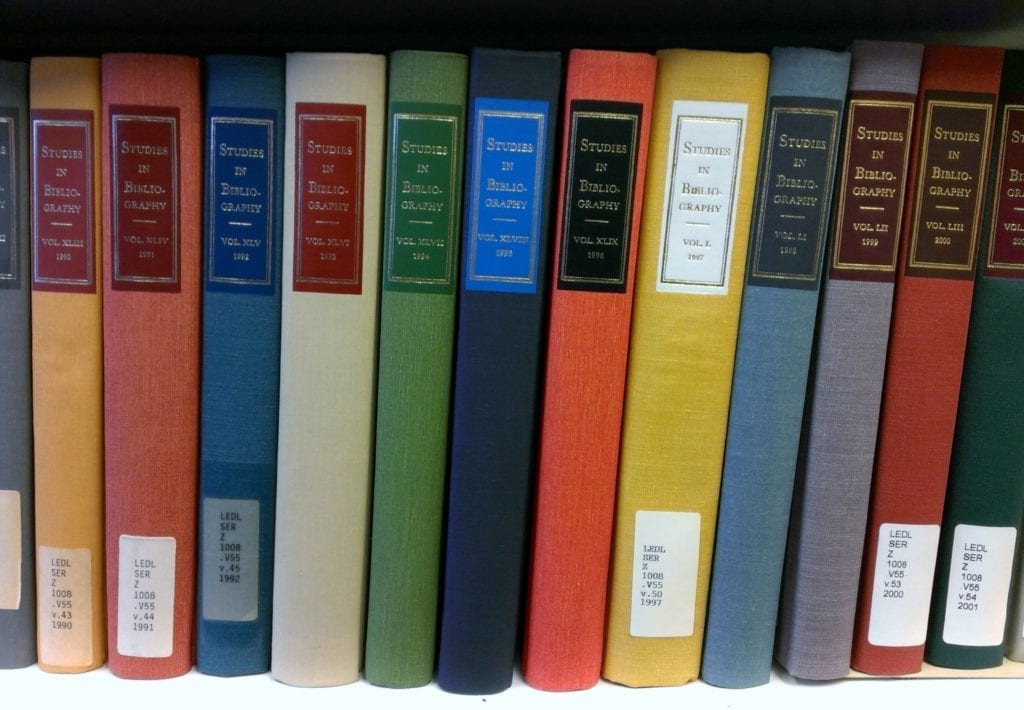

Understanding your scientific lineage is also a contributor to scientific progress—particularly if you’re adopting a new ‘family’ with which you might not be that familiar. Studies done by researchers higher up the family tree often form the basis for research done lower on the tree—either directly through study replication or revision, or indirectly through the percolation of research ideas. It’s highly likely that the great-grandchild of the initial researcher is building on that original research in some way, shape, or form.

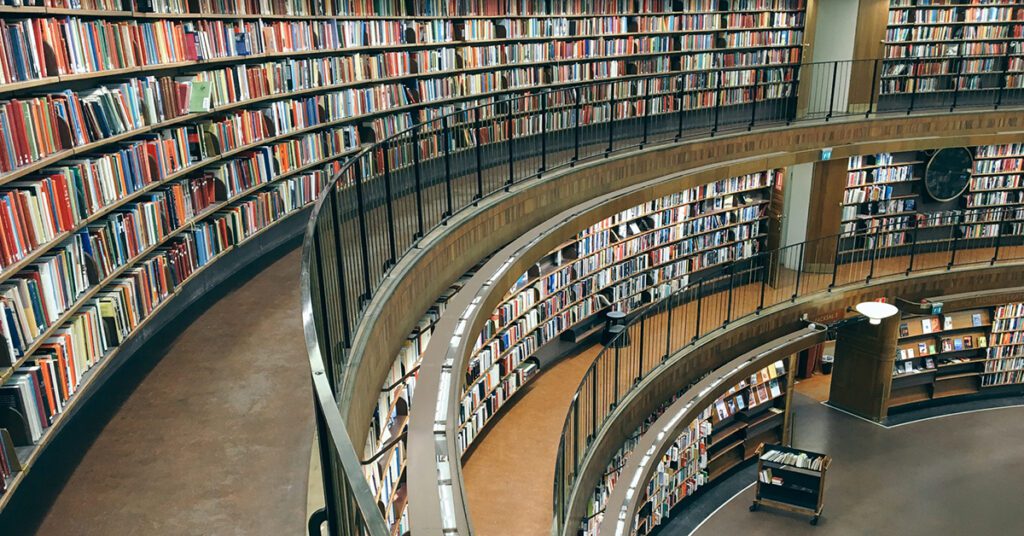

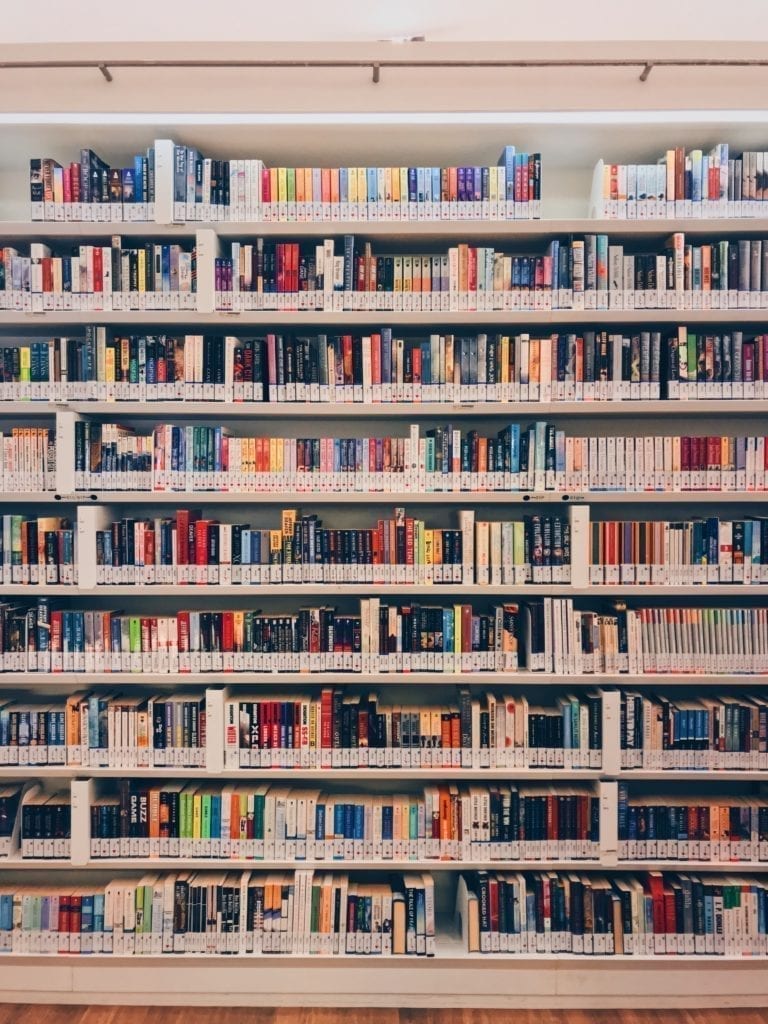

Your academic genealogy can also give you historical context for the research that has happened before your time—particularly given the overwhelming number of more recent publications now easily available online. Science only moves forward when we avoid repeating previous studies—including their mistakes—which we’re more likely to accomplish if we have a sense of our scientific heritage.

To research your academic genealogy, try PhDTree or Academic Tree. While the former is fairly incomplete for the Canadian earth and environmental science researchers I searched, you have the option of signing in to edit and add to it as required. The latter has a number of participating research areas, including chemistry, ecology, neuroscience, and other scientific fields.

Whether you are a ‘parent’ or a ‘great-grandparent’ on the scientific family tree, you can see your research field as a legacy stretching both behind and ahead of you, connecting you to both the past and to the many ‘children’ to come.