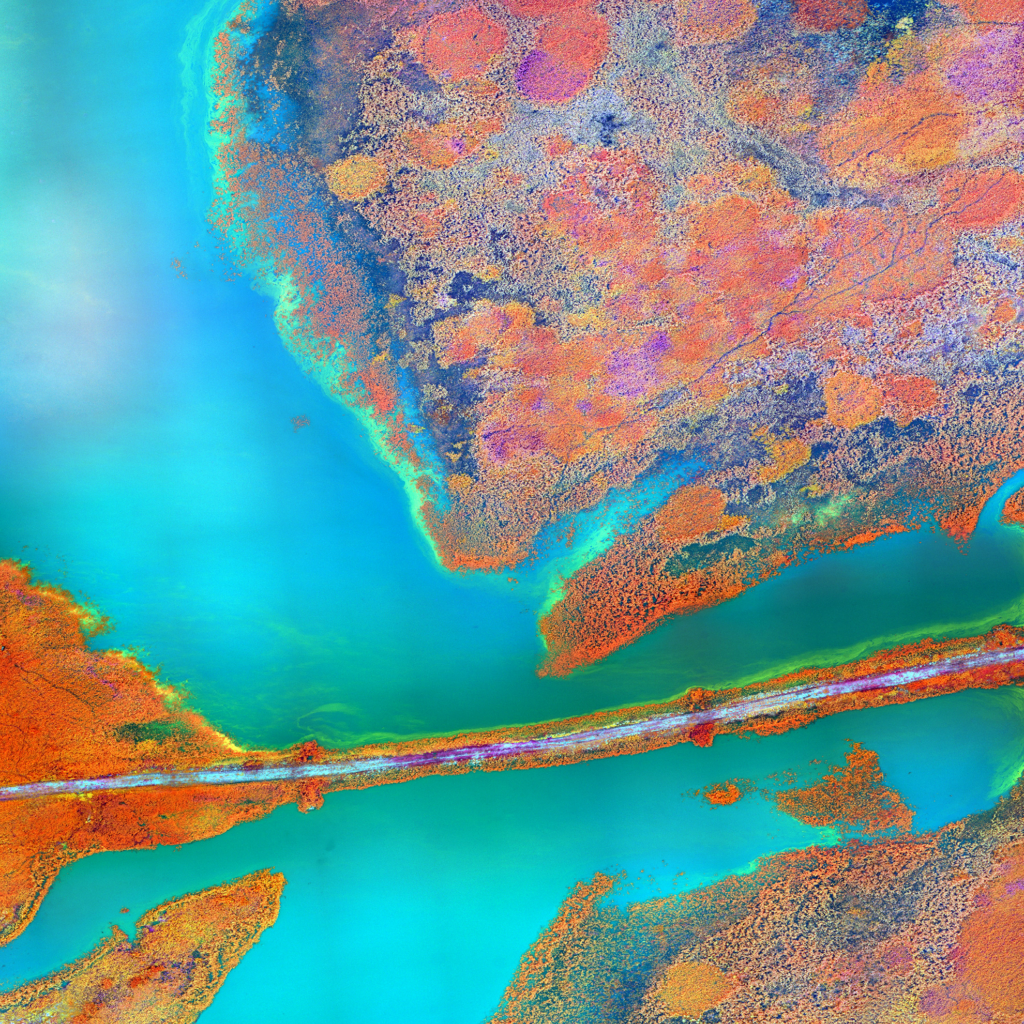

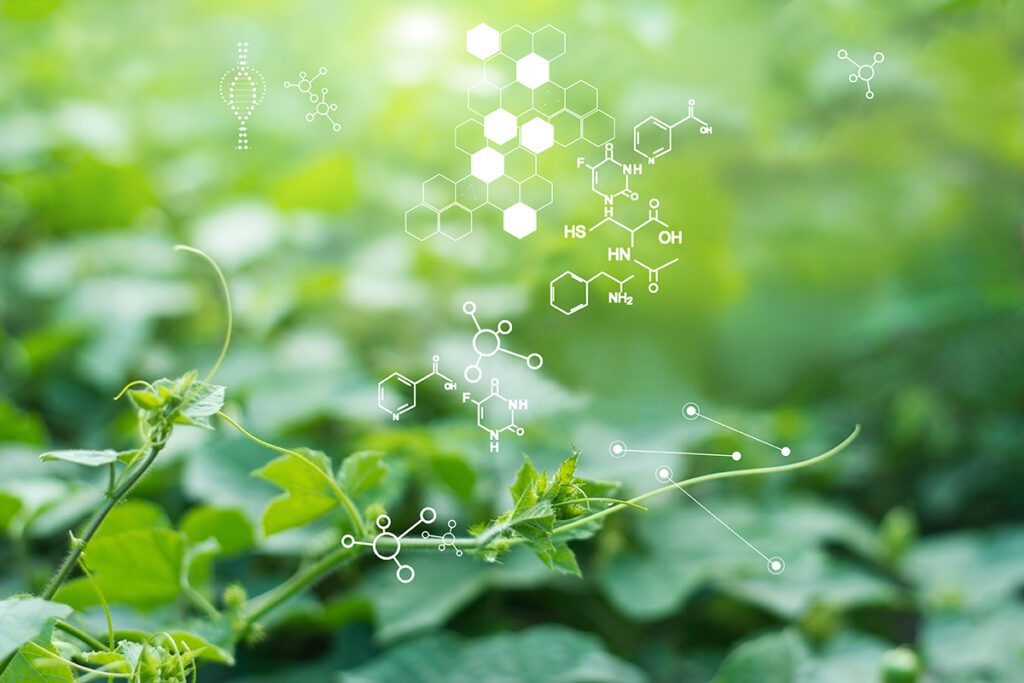

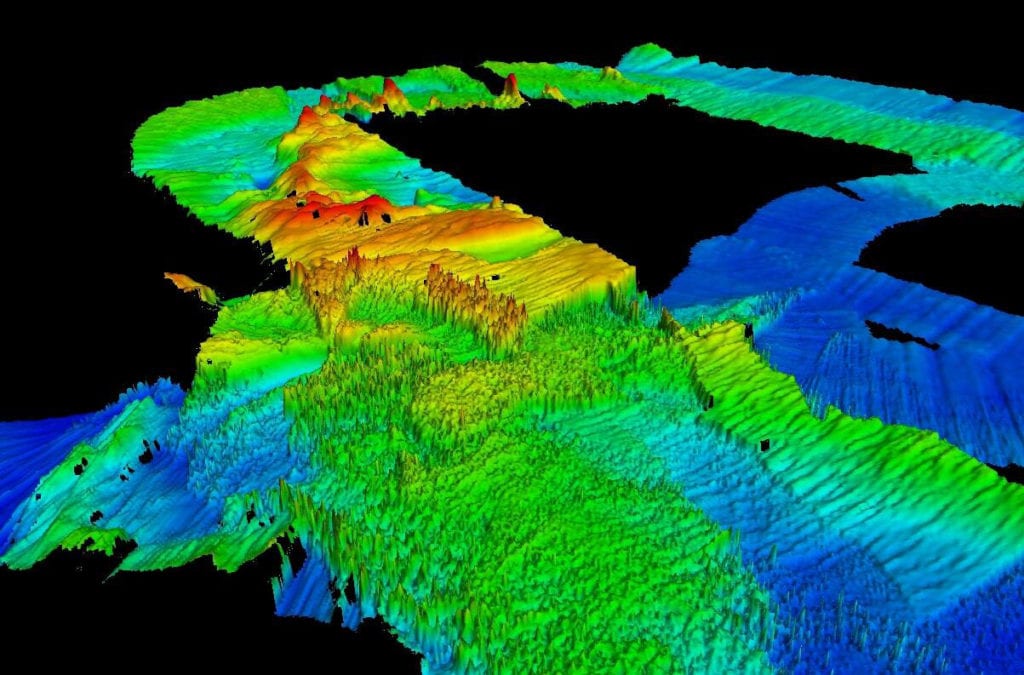

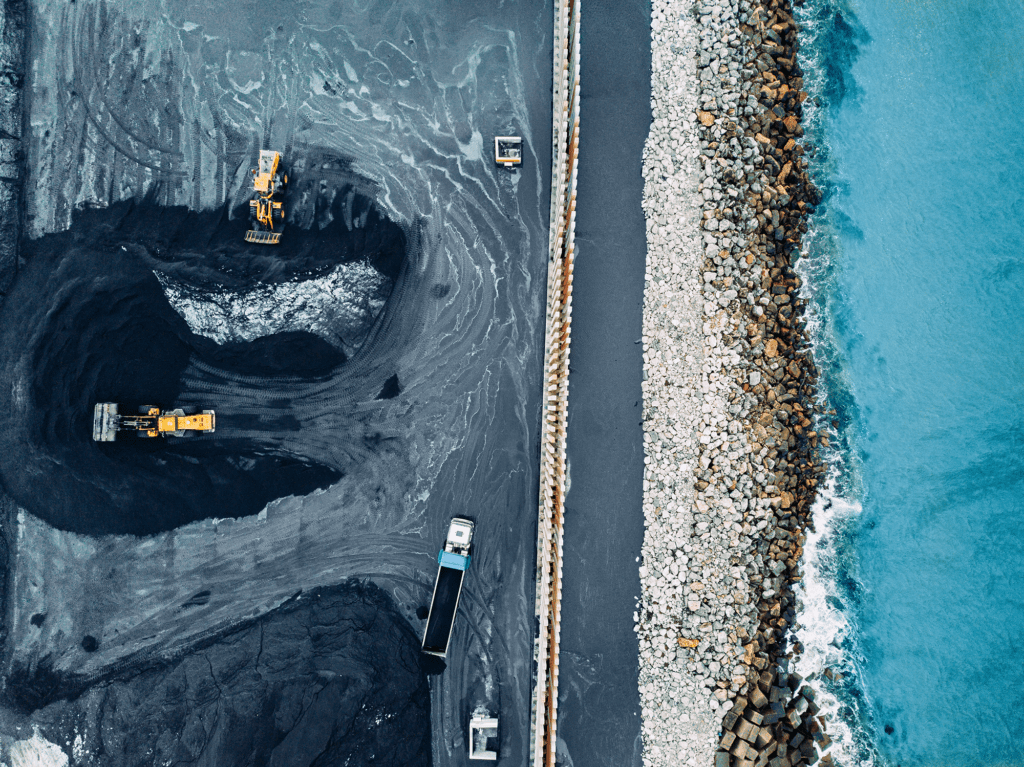

Chemical fertilizers and pesticides have greatly improved food security worldwide, but their use can have serious repercussions when it comes to agricultural sustainability. While they help plants grow, they fail to sustain soil nutrients or promote soil health. Essential trace elements are gradually depleted by repeated crop plantings, resulting in long-term damage to the soil.

Simply, it’s getting harder and harder to grow food.

“Chemical fertilizers and pesticides are really ruining the soil, and since soil is our most important resource on this planet after water, we cannot continue to do this indefinitely,” said Ann Hirsch, a professor from the Department of Molecular, Cell, and Development Biology at the University of California.

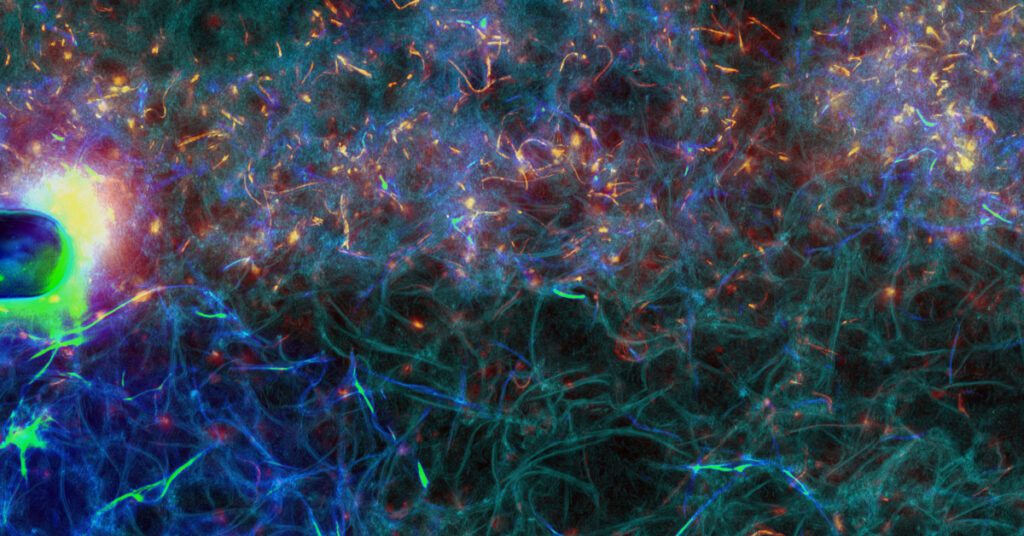

The answer for improving soil health may already be in the soil. And it’s been there all along.

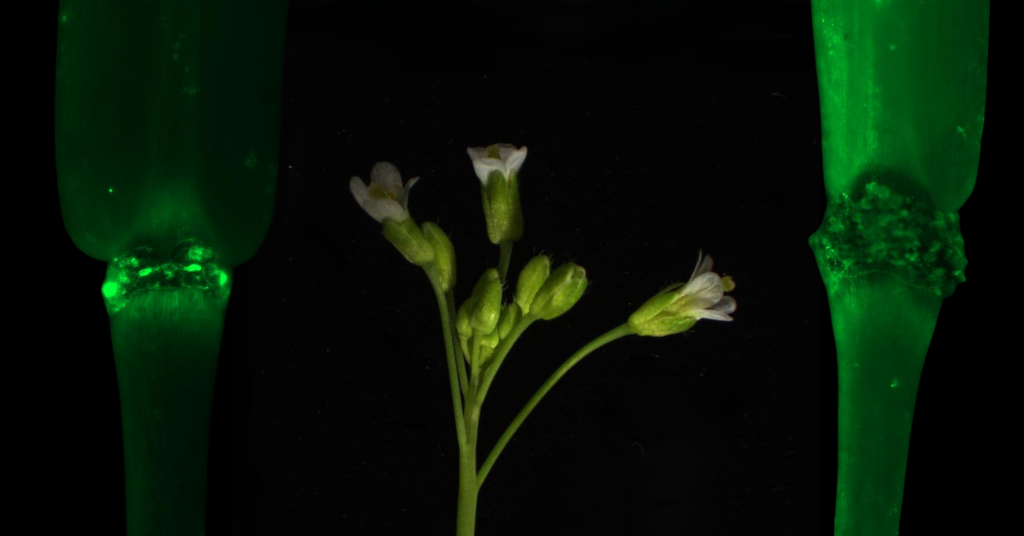

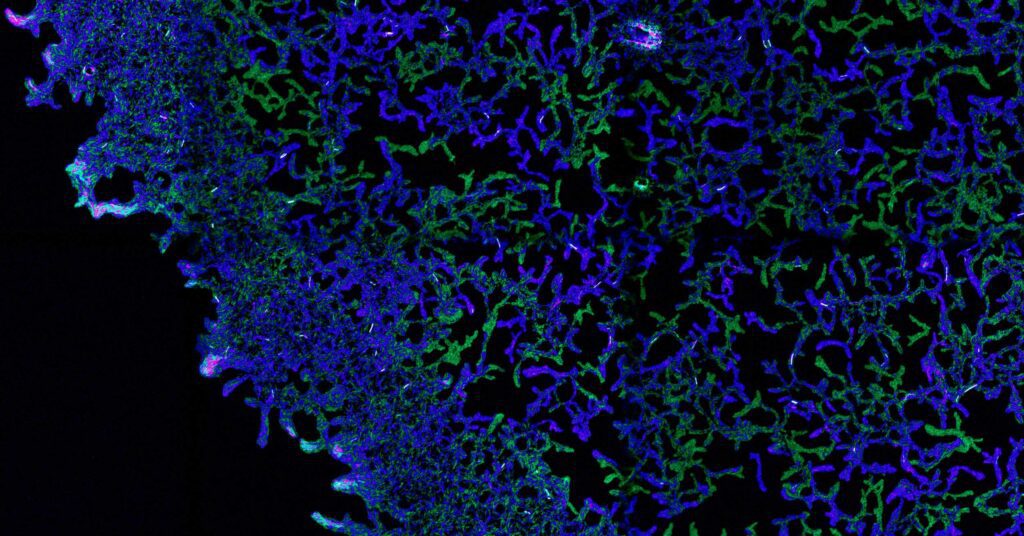

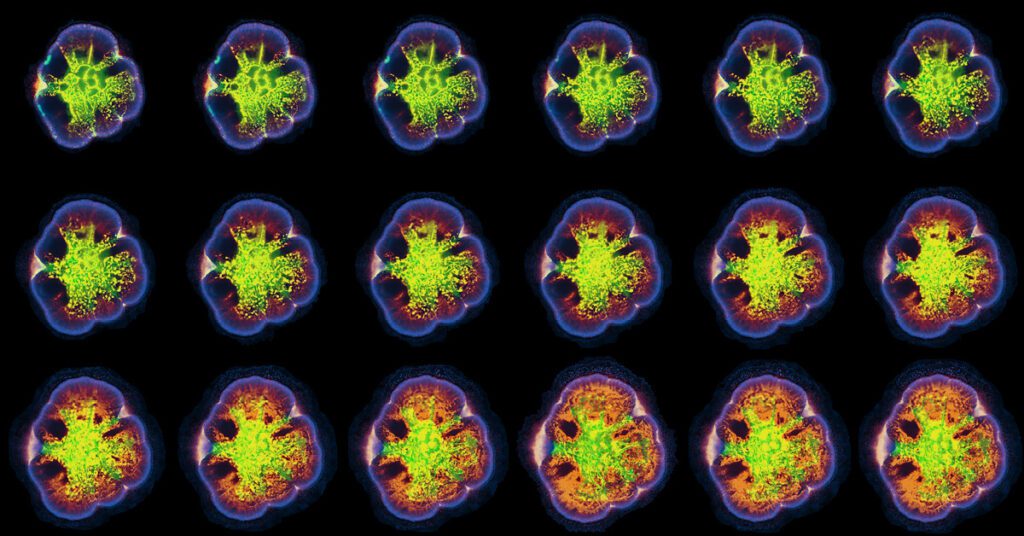

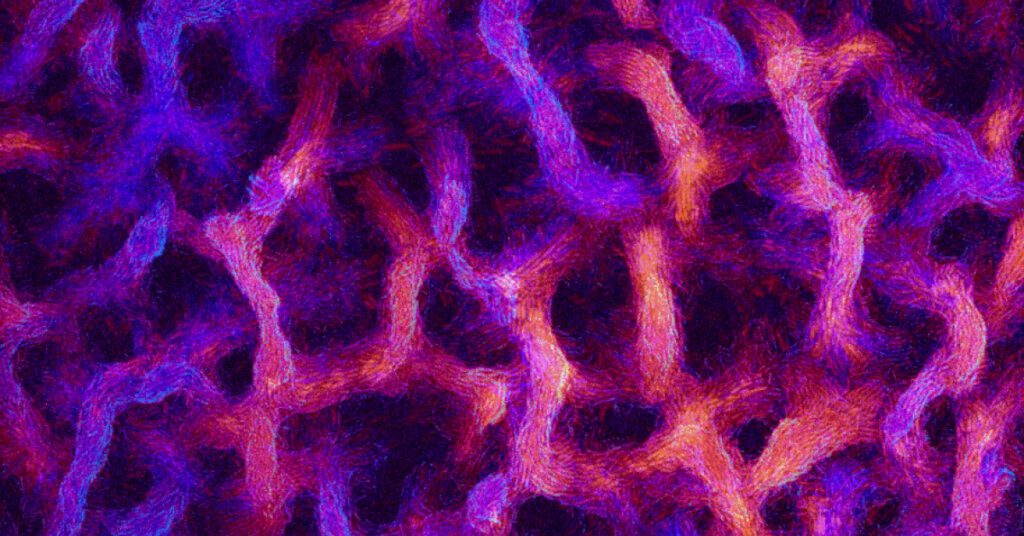

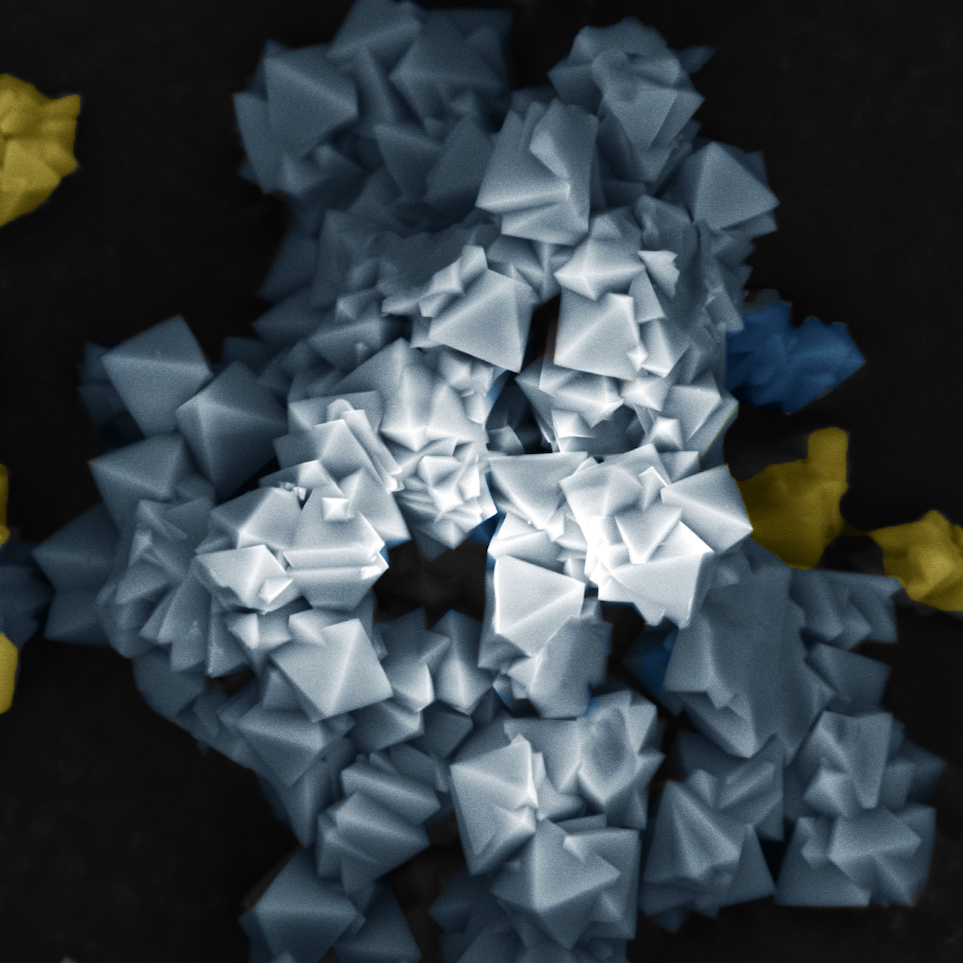

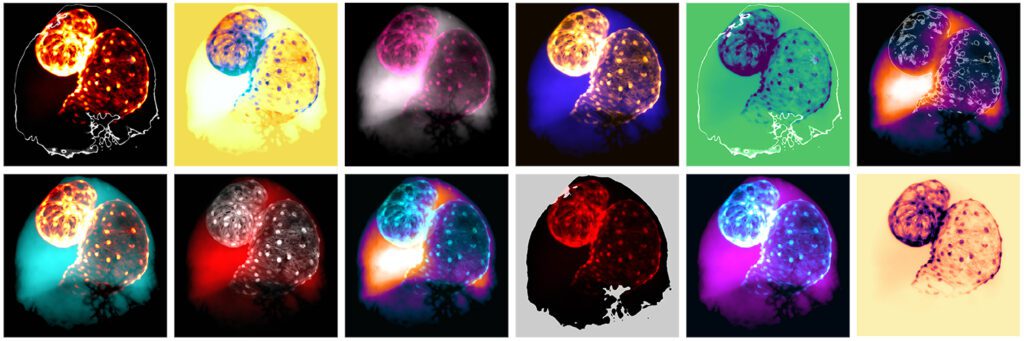

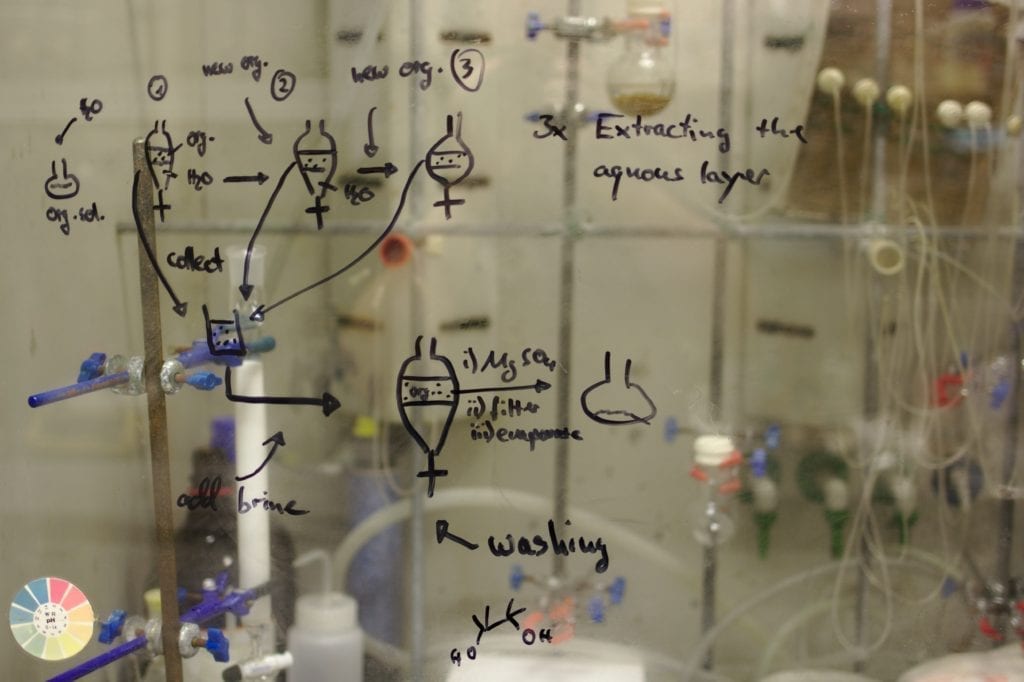

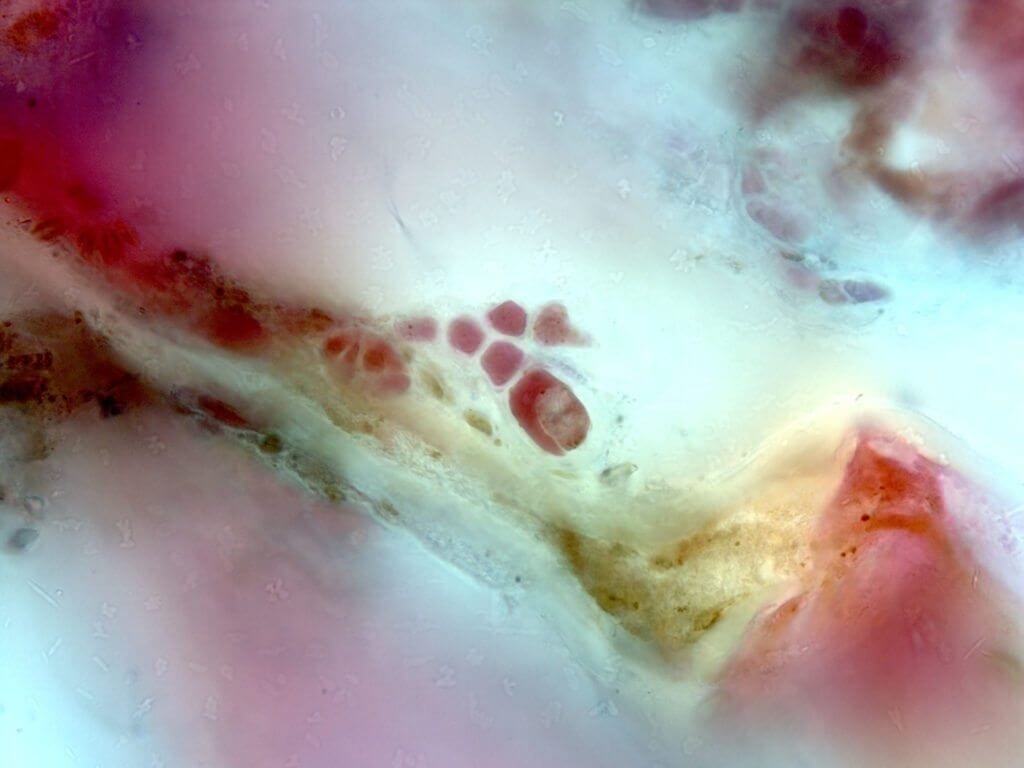

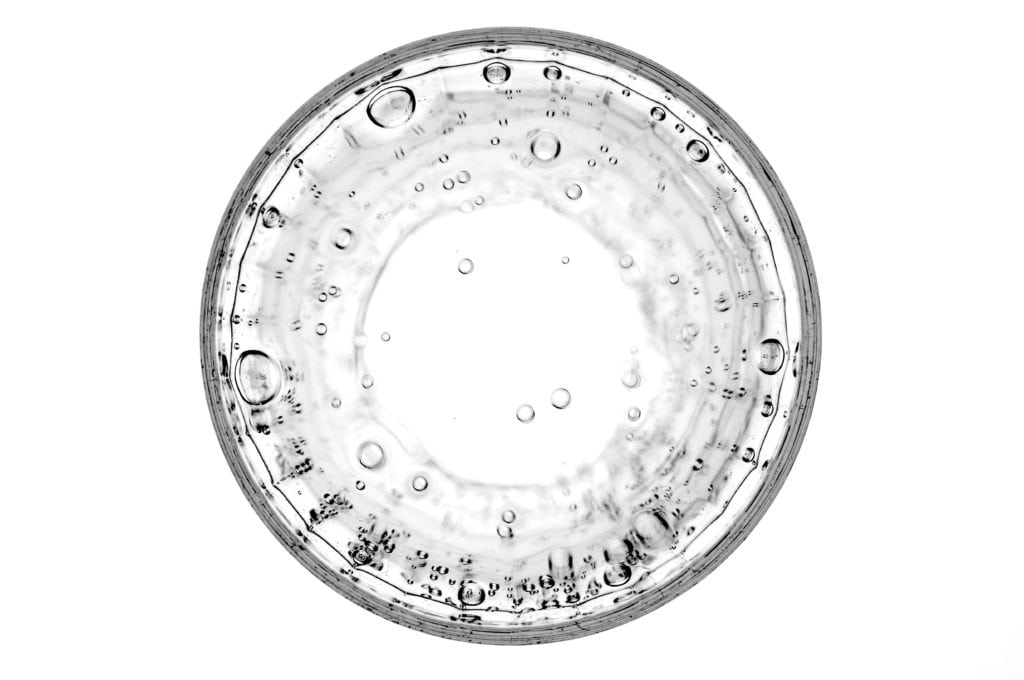

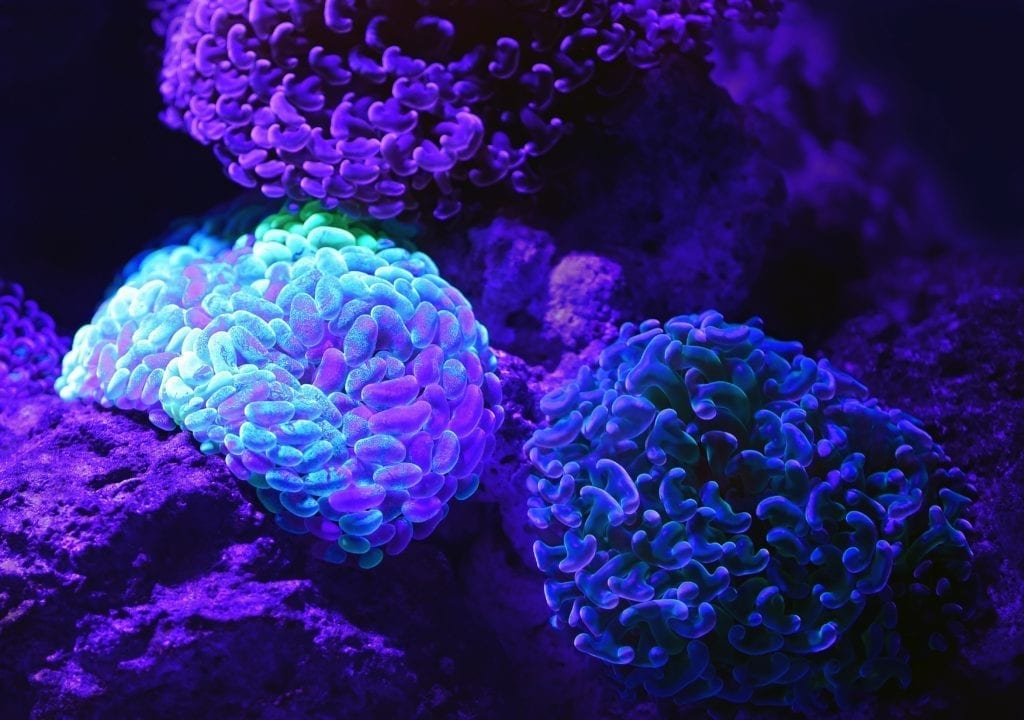

To increase global soil health, Hirsch and other researchers are trying to promote environmentally friendly plant growing methods to replace our reliance on chemical fertilizers. In a review published in the Canadian Journal of Microbiology, Hirsch and colleagues explored the use of bioinoculants—microorganisms that establish mutually beneficial relationships with crops—as a sustainable solution to the over usage of pesticides. Bioinoculants, typically fungi and bacteria, can increase crop yield by enhancing plant growth, controlling disease, and providing minerals for plants.

“We know that after years of adding fertilizers to plants that it has led to a change in the natural microflora in the soil. I think ultimately, it’s to our detriment,” said Hirsch. “Our goal is to see if we can, I hate to use the cliché, go back to nature, but find these beneficial bacteria that are always there.”

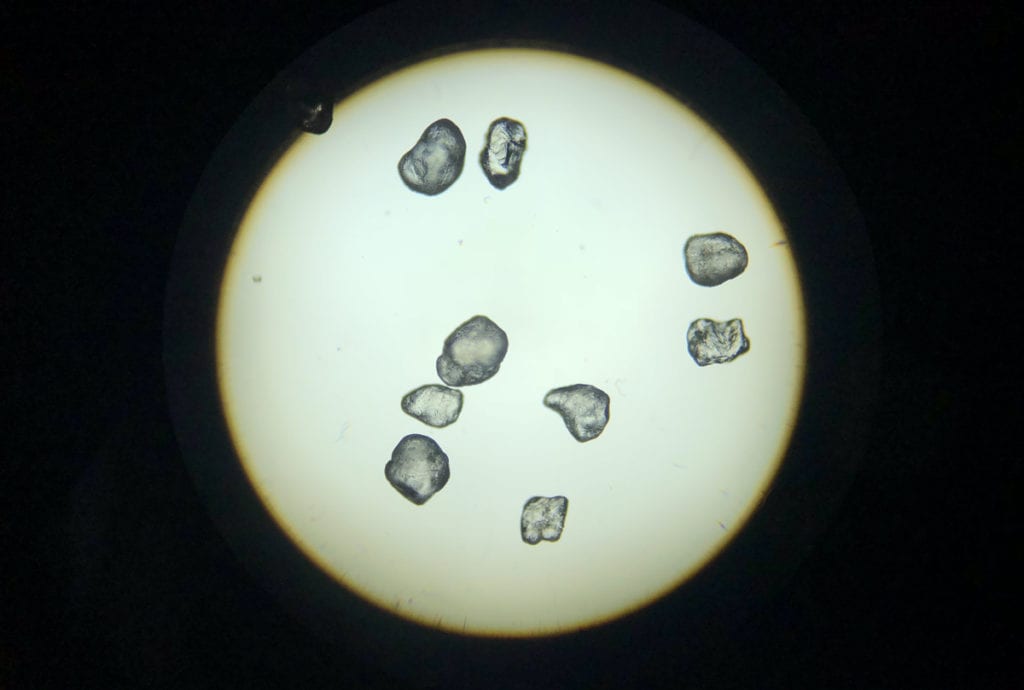

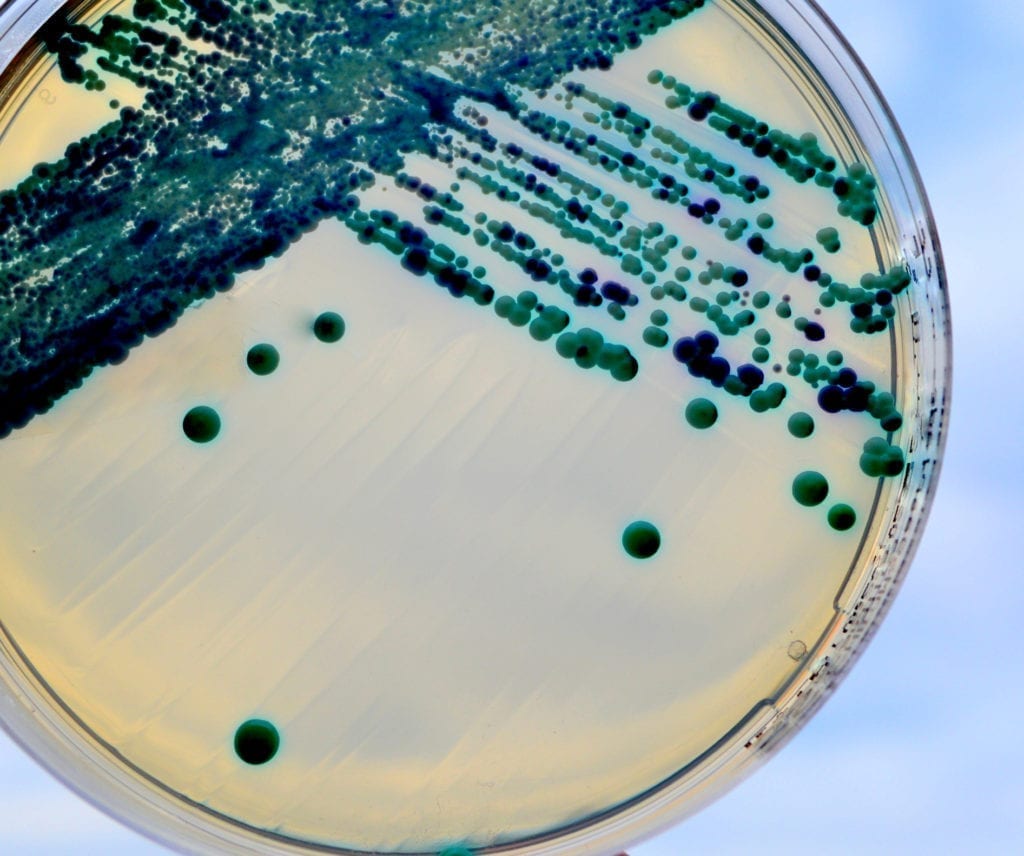

The authors looked at various microbes, such as ones isolated from alfalfa roots, to see their effects on target crops and non-target organisms.

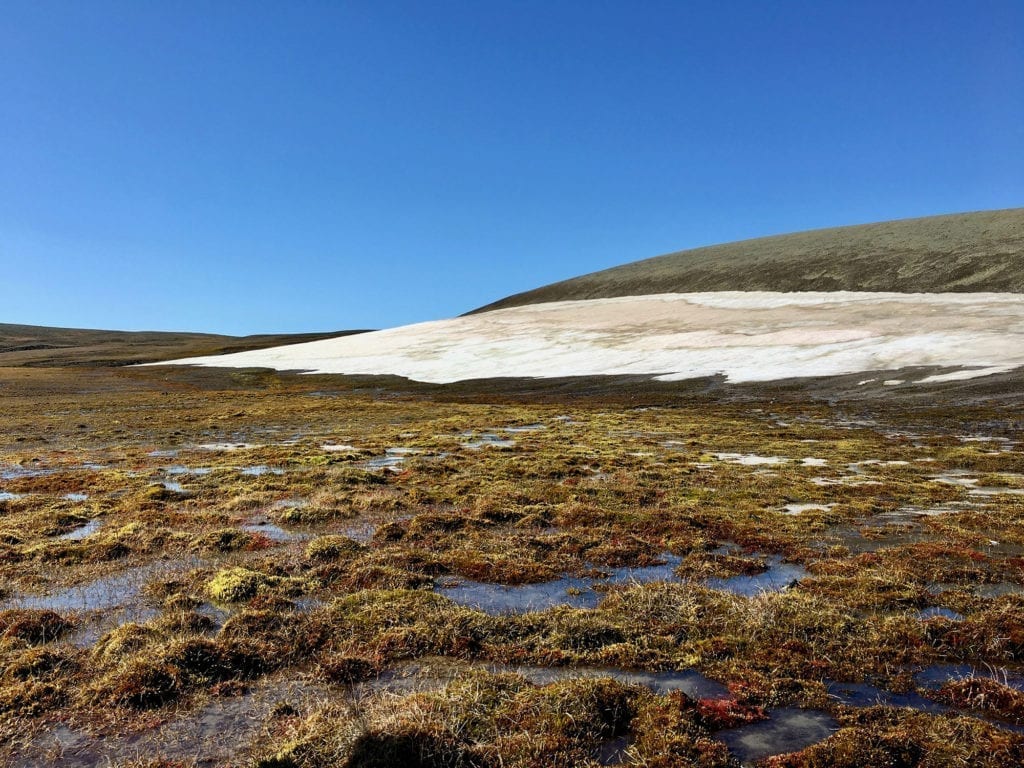

The paper describes how growth promoting microbes can help plants grow under extreme conditions such as nutrient deficiency, aridity, salinity, and drought.

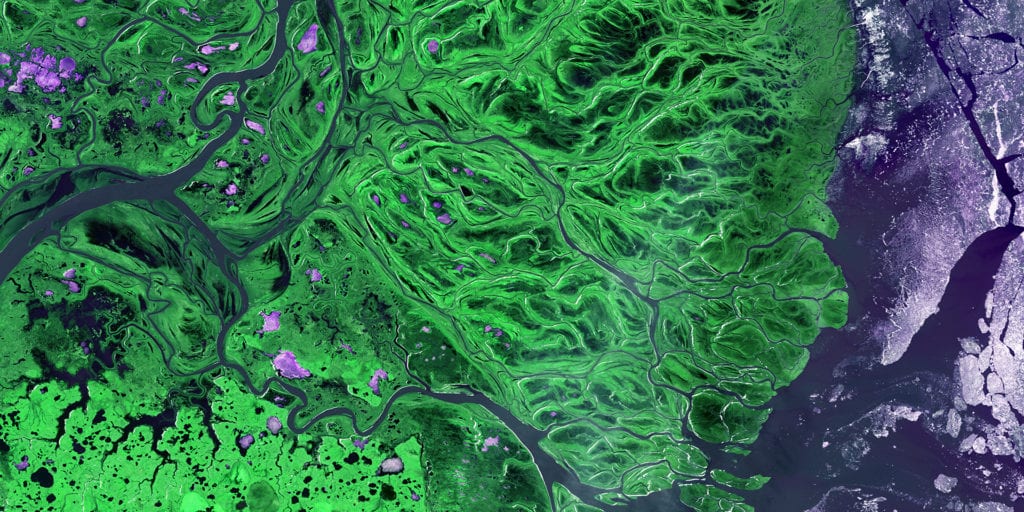

According to the study, as our population grows, it will be important to find ways to improve soil quality in various parts of the world to increase food production. While it may be expensive to research bioinoculants, Hirsch said the cost of using chemicals is much higher.

“We can no longer continue the way we’re going, especially in countries that will have the greatest growth spurts, like in Asia and Africa. Already those soils are over-extended,” said Hirsch. “We’re very lucky in North America. We have incredibly good soils. We don’t need as much nitrogen fertilizers, such as in Pakistan, where the soils are really bad.”

However, there are still some unknowns when it comes to plant growth-promoting microbes, such as how successful lab cultivated microbes are in field conditions and vice versa. Only approximately 1% of environmental microbes can be cultivated.

“One of the things, in my opinion, that would be nice, would be to test what we found in the field. That’s the missing link for us here. We have limited research to take that into the real world,” said Maskit Maymon, one of the study co-authors.

“Many times, you can get a lab experiment to work really well then when you transfer it to real soil under conditions, the experiment doesn’t go any further,” said Hirsch.

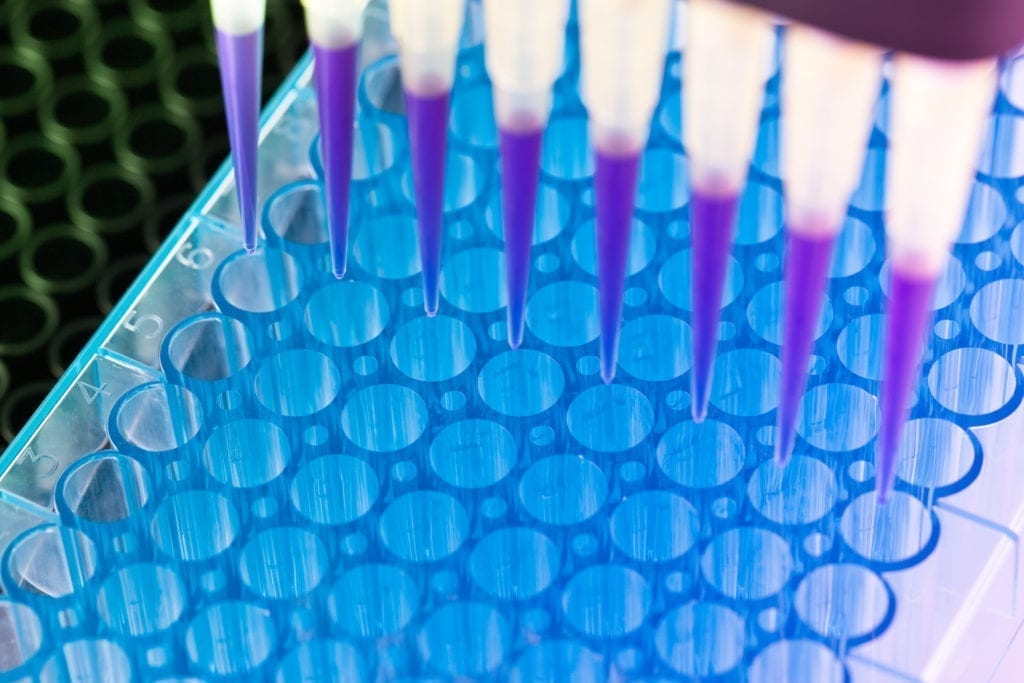

Thus, the authors have sent some microbes to other locations such as Kansas to undergo field testing.

Additionally, little is known about the health consequences of bioinoculants and whether or not they cause unintended harm on non-target organisms such as humans. The authors of the paper said that each growth-promoting microbe must be vigorously tested to make sure there are no ill effects before being used.

The commercialization of these inoculants is another hurdle—the inoculants are not as fast-acting or consistent as their chemical fertilizer counterparts, and farmers will require a higher degree of expertise in applying the inoculants.

The authors acknowledge that there is still much to learn and that’s what makes this research exciting.

“We’re just breaking the tip of the iceberg,” said Hirsch.

And Hirsch’s work has already garnered commercial interest. “Companies are aware that it’s time to change our ways,” added Maymon.

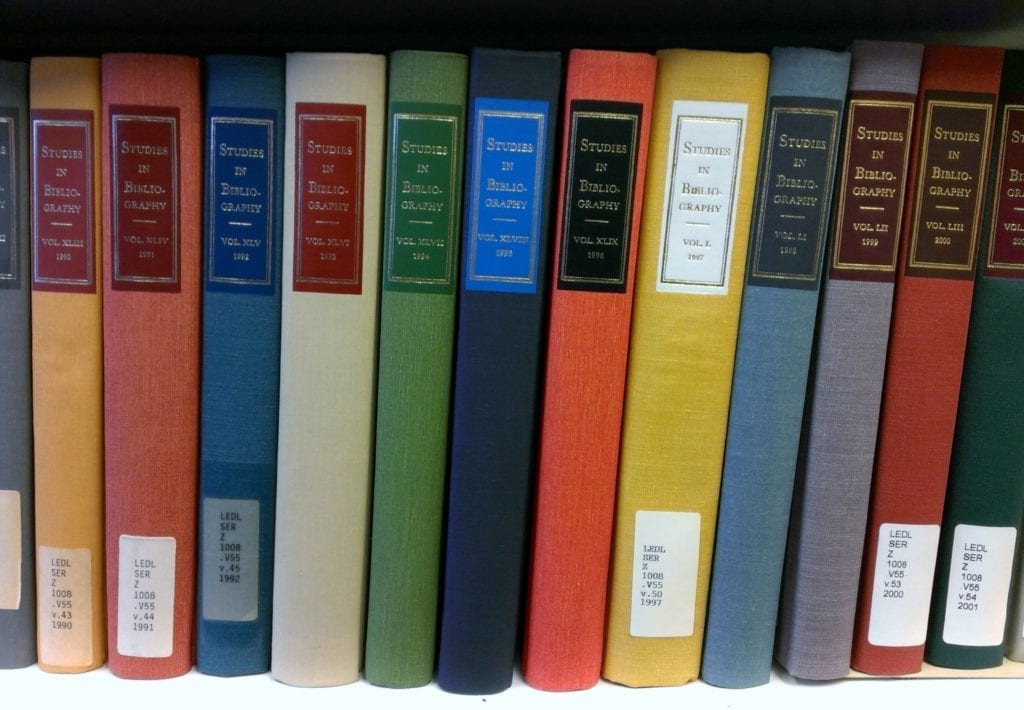

Read the full paper: Engineering root microbiomes for healthier crops and soils using beneficial, environmentally safe bacteria in the Canadian Journal of Microbiology.