Stroll along the periodicals of a library and the passage of time is evident. You may first notice the exterior of the journal itself. The binding is soft, worn with wear. The pages are browning with a musty aroma. The style of lettering is regal in comparison to Arial’s contours.

Back in the Leddy Library to continue my bibliotheca experience, I stopped in front of the rows of Journal of Mental Science. The collection at Leddy spans from 1880 to 1962. Then volumes of British Journal of Psychiatry appear for the years 1964 to 1992; the title of the journal was changed in 1963. But missing from the shelves are volumes of Asylum Journal, the original name of the journal when it was first published in 1853. Encompassed within the history of a journal is the history of the science itself. Indeed, the field of mental science/psychiatry has evolved considerably over the last 150 years. From the pioneers in your field and the archetypal methodologies they used to the inception of theoretical frameworks and temporal flux in terminology – delving into this history can be rewarding.

My research falls within the category of fisheries science. As a Canadian, when taking a historical perspective on fisheries science, I think of salmon. On the west coast, Pacific salmon (Oncorhynchus spp.) have swum the rivers of British Columbia since the Cordilleran ice sheet melted ~11,000 years ago. Indigenous populations in the province have interacted with salmon since then. Pacific salmon are abundant today. On the east coast, Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) are, well, I am less familiar with their history but needless to say their present-day abundance is regrettably scant.

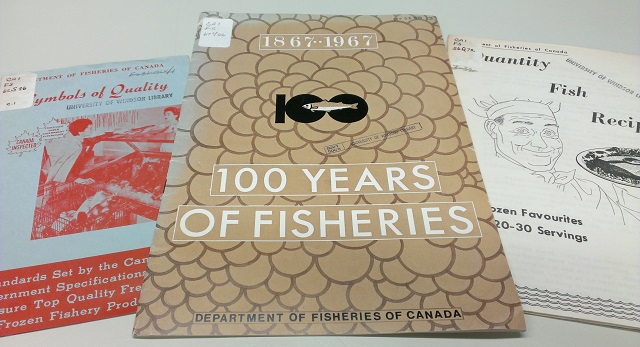

How much of this iconic species’ history could I uncover at the library? Leddy surprised me. I located over a dozen shelves of Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) holdings. I expected the majority of this collection to be reports on fisheries management and numbers of fish caught – a quantitative and formal collection limited in its scope for narrative. There were indeed reports including a Lobster Pricing Analysis from 1991, A Guide to Longline Mussel Culture in Newfoundland from 1988, A Technique for Salting Lean Minced Fish from 1977, and a supplement from the Eleventh Annual Report of the Minister of Marine and Fisheries stating that the “total value of the productions of the Fisheries of Canada in 1879 [was] $13,529,254.91.” But there were also brochures on fish inspection labels, DFO’s centennial and recipe books! I found the authoritative anthology Freshwater Fishes of Canada by Scott and Crossman and nearby The Cruise of Neptune by A.P. Low. Officially known as “Report on the Dominion Government expedition to Hudson Bay and the Arctic islands on board the D.G.S. Neptune, 1903-1904”, this book is a detailed account that describes the geology, whaling and Indigenous culture of Canada’s Arctic at the beginning of the 20th century. I was thrilled with these finds.

Why exactly I had an emotive response to old fisheries literature is likely a combination of 1) a spontaneous surge of creativity, 2) a wistful connection to a different era of scientific discovery, and 3) uncomfortable thoughts that documents like this perished in the garbage dump of 2013.

I was surprised again when I found the 1985 book The Atlantic Salmon in the History of North America by R.W. Dunfield. Not to be confused with the technical records on catch statistics of Atlantic salmon, this DFO publication is an attentive and thoughtful retelling of this fish’s geographical, cultural and political history up to 1867. At first I was disappointed at the truncated timeline of this book, but soon realized that the tumultuous history of Atlantic salmon in Canada’s freshwater pinnacled by the year of Canada’s birth. Atlantic salmon were revered by the Aboriginals, capitalized upon by European explorers and their life cycle an enigma to all. Knowing where fish are without knowing why would build the plot for another tale of the demise of a natural resource. The antagonist being a multi-armed anthropogenic entity. One arm the expansive agriculture, another arm the booming timber industry – both arms wielding the power to cripple accessibility and health of the rivers and lakes. A third arm the advancements in fishing gear and a fourth arm unregulated fishing practices left fish overpowered. I tried to put this in a temporal context. Well before the radio and telephone were invented, many Atlantic salmon populations were already destined for extirpation. Although this book’s content is dense with information, it is balanced with whimsical cartoons that mark the start of each chapter, and both clever and sobering anecdotes from court records, ship captains, Cartier and Champlain. Again, literary nuggets I was appreciative to find.

From Leddy I ended up browsing my own modest library, 1/3 of which I must admit is comprised of Lucy Maud Montgomery’s prose. Last year, I stopped in at Powell’s Books after the 2015 American Fisheries Society’s annual meeting in Portland (be sure to read the Making Waves blog series for a summary of the science communication symposium from this conference). I picked up A Fine Kettle of Fish Stories and To Sea & Back. I grabbed the latter off my bookshelf and dove into a spectacular chronicle of the Atlantic salmon in Scotland’s rivers. I learned of piscine “cocks” and “hens”, which are the “bucks” and “does” of Pacific salmon or simply male and female salmon. I was treated to an account of the stone salmon at Glamis – a carving of an Atlantic salmon by the Picts, humans who dwelled in Scotland in the early Middle Ages. I now know that European smelt smell like cucumber and that killer whales may be referred to colloquially as “grampus”, a relic term from their former taxonomic classification, Grampus orca. The Atlantic salmon’s legacy took me east of Canada’s Atlantic shoreline, where to next?

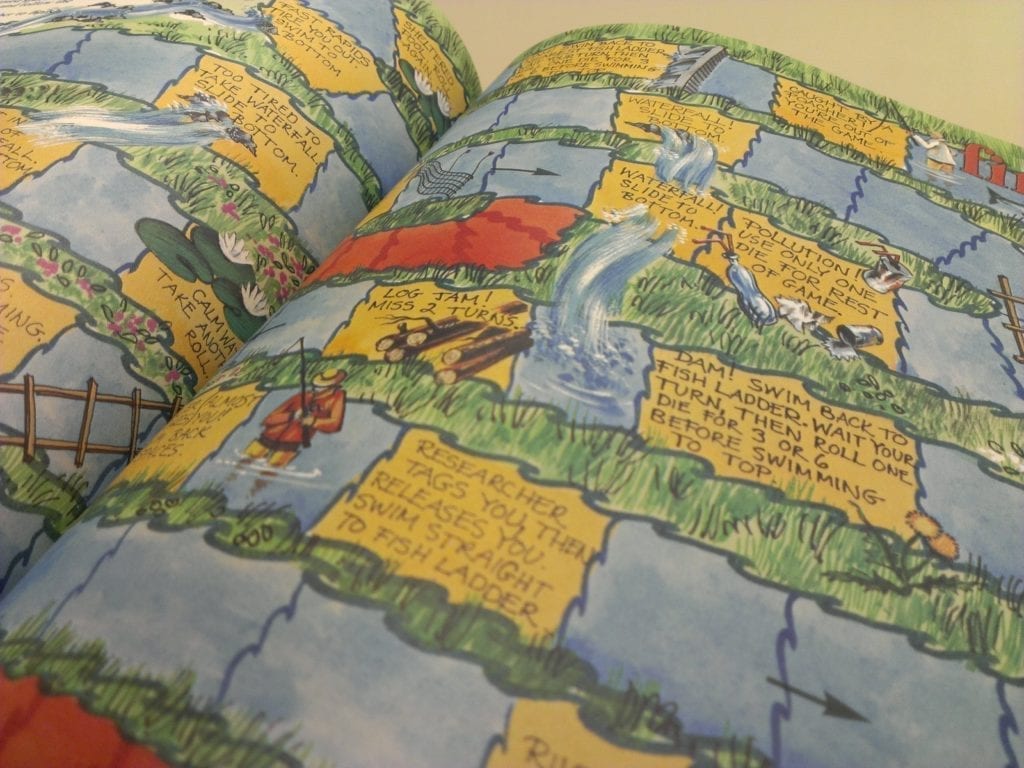

During my first visits to Leddy I happened upon the inaugural issues of OWL magazine. While browsing the colourful pages of a 1977 issue my eyes fells upon the “Salmo” The Great Atlantic Salmon Game. I returned to the periodicals in Leddy and found the game. I now knew that this game described remnant Atlantic salmon that existed beyond the history of which I had already read. In fact, this game was describing an even smaller number of Atlantic salmon that existed beyond the ravenous marine commercial fishery of the 1960s and 1970s.

Transitioning from the library to the field, the culmination of this Salmo venture was catching an Atlantic salmon as part of a scientific tagging study in Lake Ontario. The body shape was streamlined and solid. The aquamarine colouring of its back contrasted with its silver sheen and delicate spattering of black marks – it’s simply a beautiful fish. I know this fish isn’t the same as the ones I read about. This fish likely started its life in captivity and was released into the wild as a juvenile as part of efforts to restore Atlantic salmon in Lake Ontario. The electronic tag attached to this fish will store information on the depths of water at which this fish will explore.

The library is a deserving starting point for satisfying our constantly shifting curiosities, whether they are historical in nature or not. Migration is likely to occur during acquisition of new knowledge. I began at the library, found myself at home, returned to the library and ultimately ended up on the water where the very thing I was investigating lived! What depths will you explore?