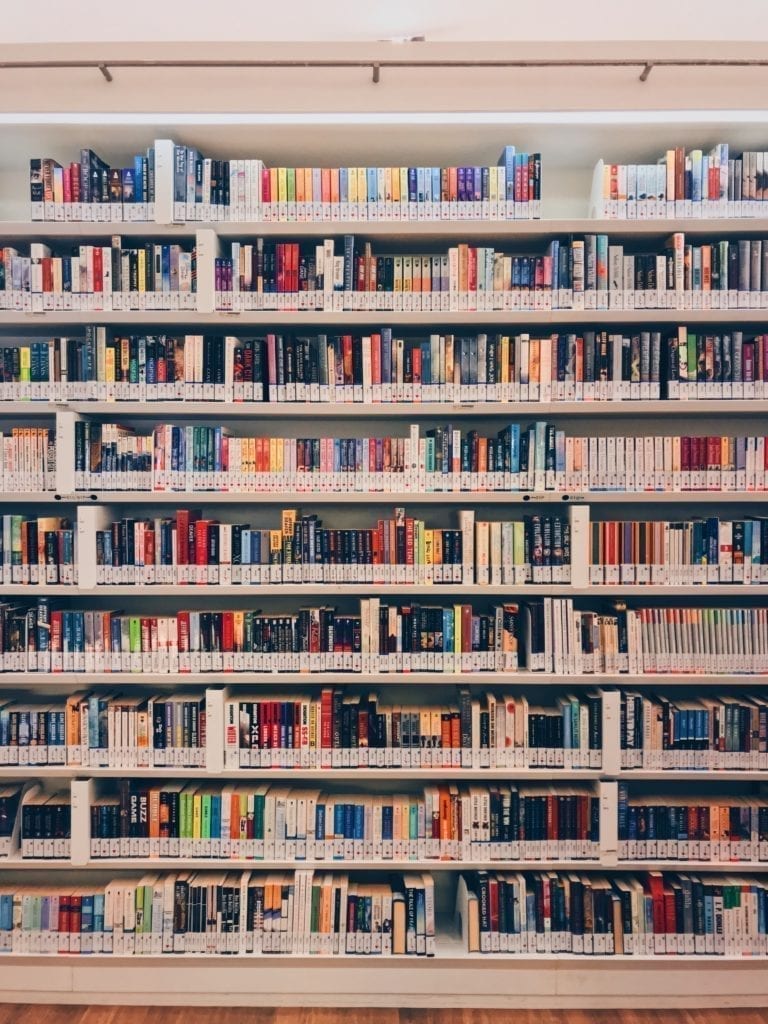

You’ve likely heard about citizen science in the news, at conferences, and around the halls and research labs of universities and colleges. But how does it work – and why should you get involved?

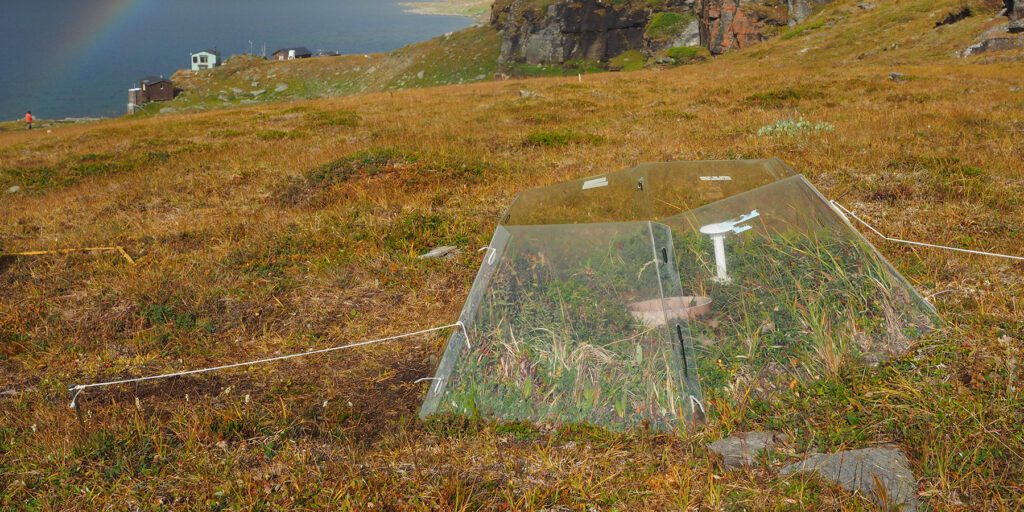

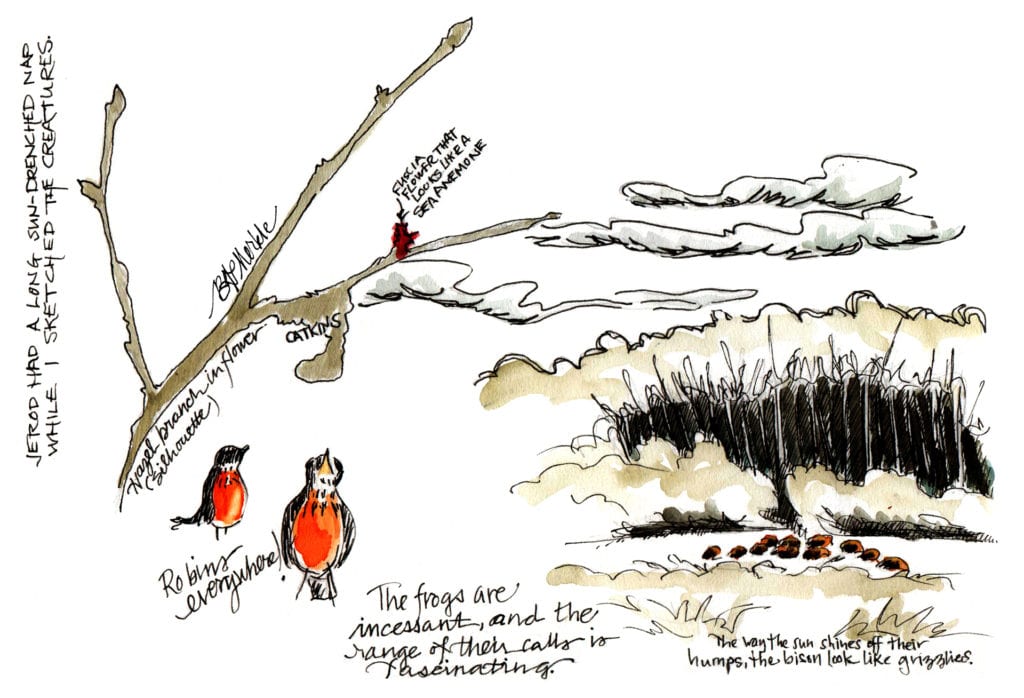

Citizen science is defined as “work in which volunteers partner with scientists to answer real-world questions.” It’s been around for quite some time, but hasn’t always been described as such. The Christmas Bird Count, for example, started in 1900 with an American ornithologist and is now conducted annually at 2000 locations across Canada (and other countries). While it’s a great example of citizen science, it was likely originally just called ‘birding.’ A more recent example of ecologically-focused citizen science is BioBlitzes, which started in 1996 and involve volunteers in an intensive one-day inventory of all species in a specific area.

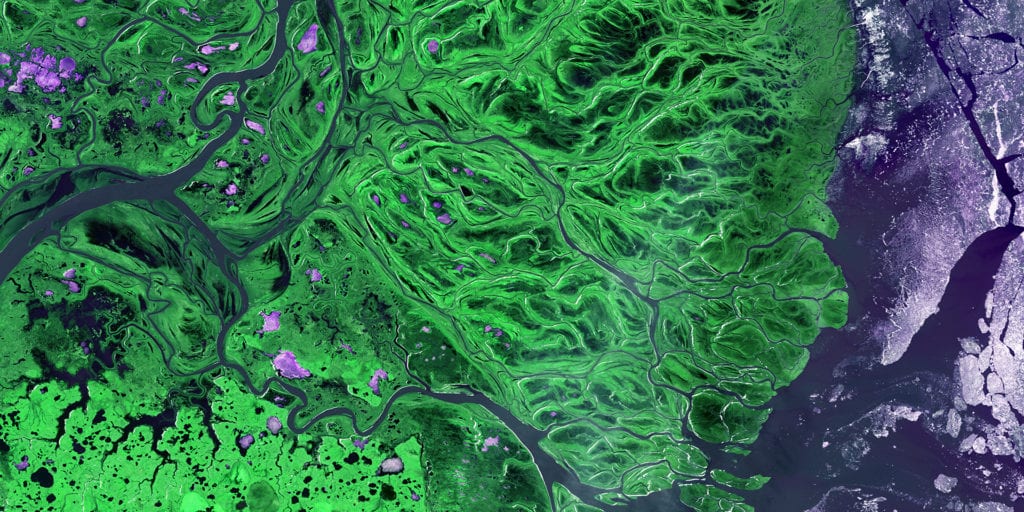

While these examples involve volunteers interacting directly with nature, there are other options outside of biology. A well-advertised citizen science project in hockey-proud Canada is Wilfrid Laurier University’s RinkWatch, started by geographers Dr. Robert McLeman and Dr. Colin Robertson in 2012. They wanted to find out if a Montreal scientists’ prediction that Canadians would see a reduction in future outdoor skating days was true. To do so, they’re tracking the number of days that outdoor rinks across the country are skateable. Another quintessentially Canadian project is Dr. Richard Kelly’s SnowTweets project out of the University of Waterloo, which collects snow depth data from around the globe and uses it to validate satellite observations.

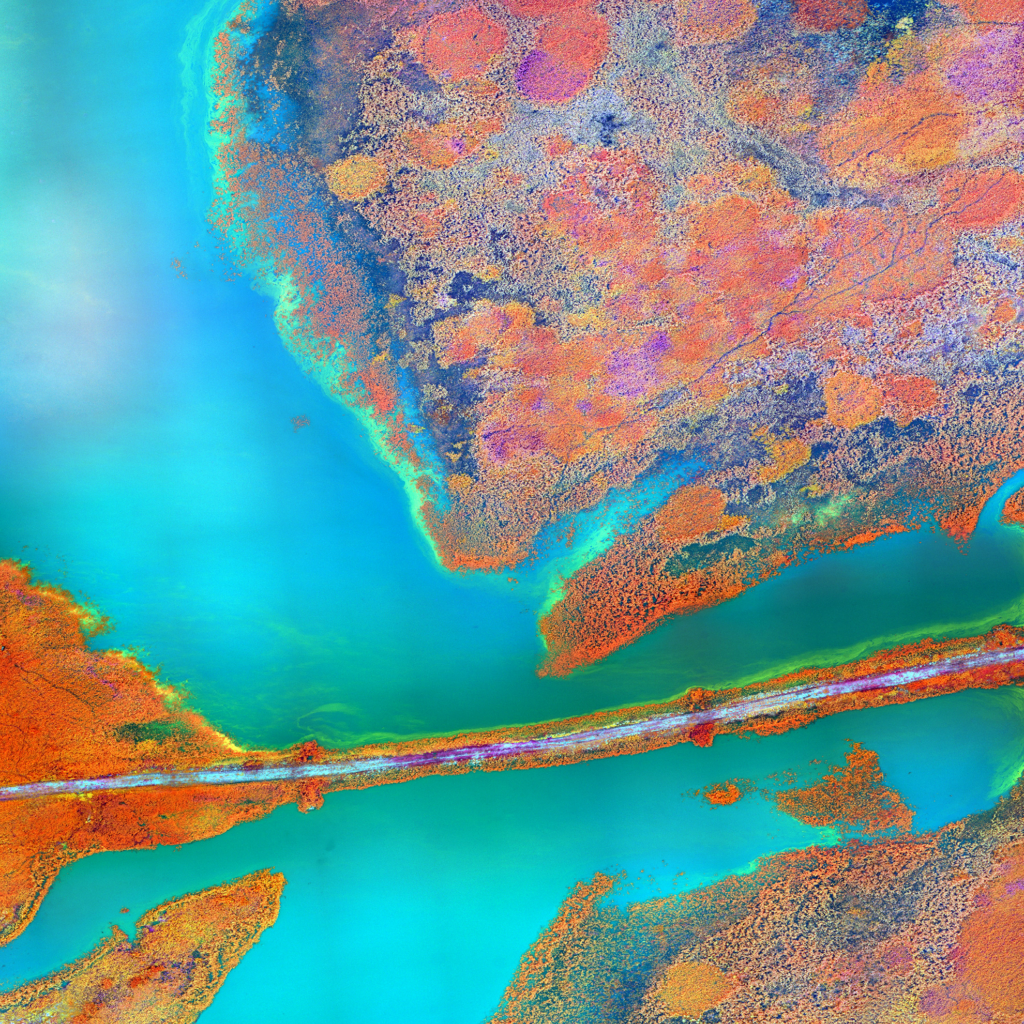

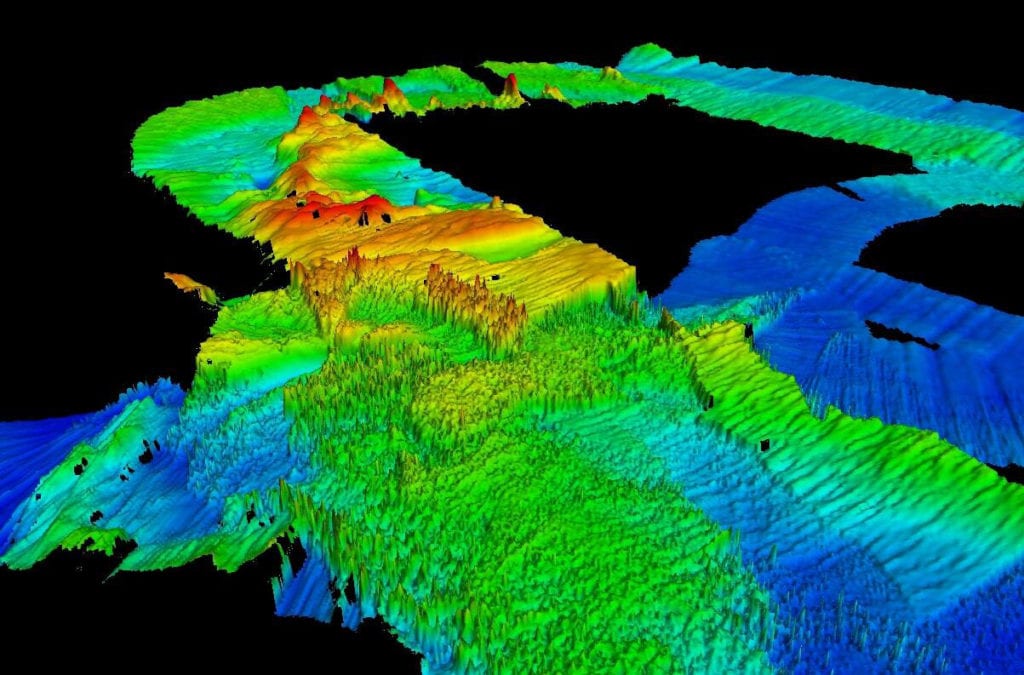

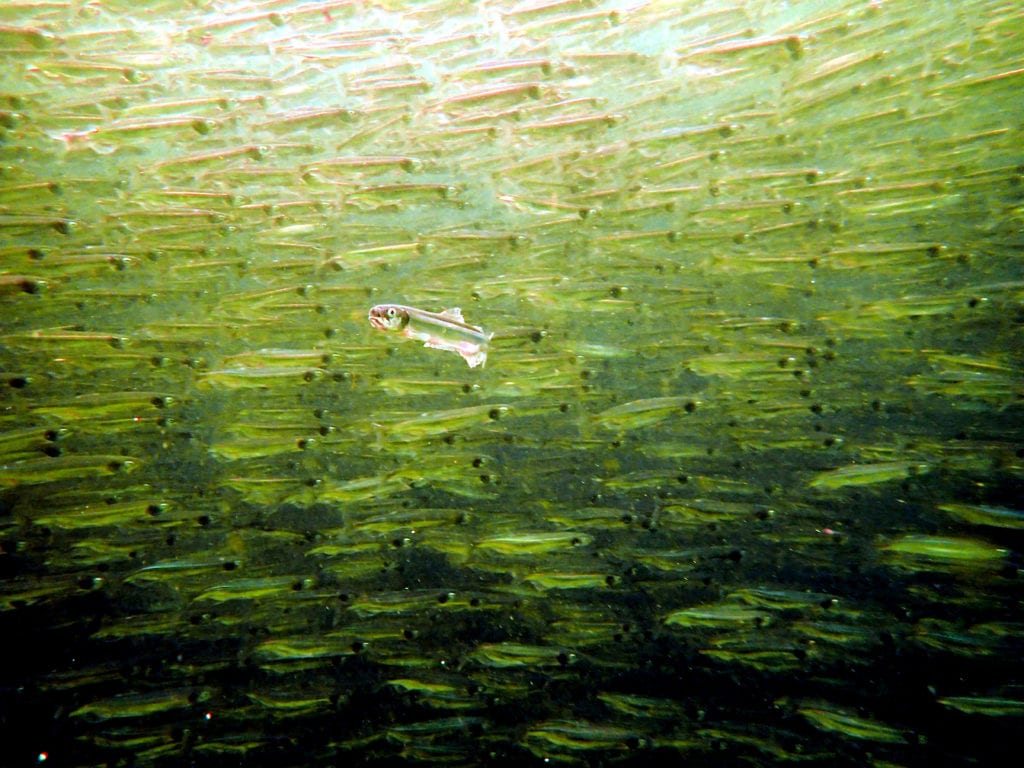

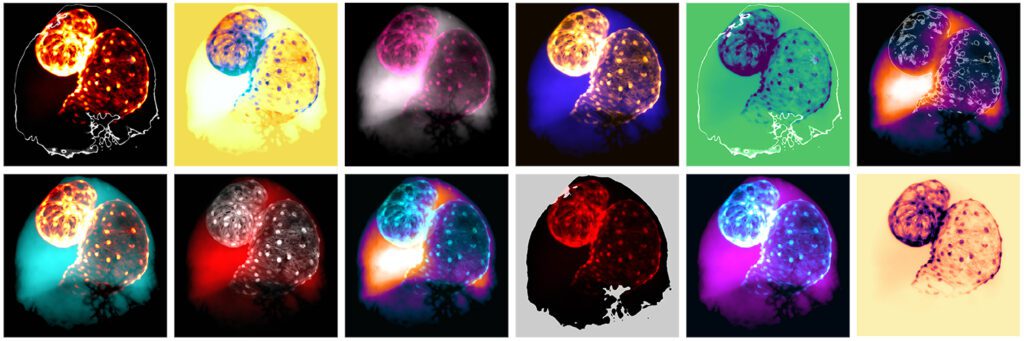

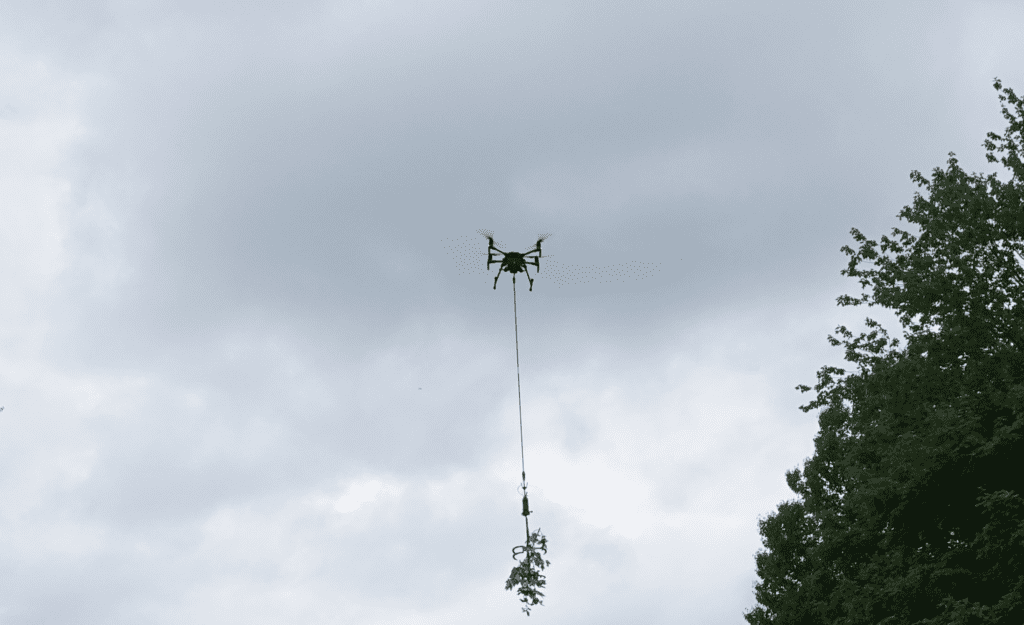

For those who aren’t keen on getting dirty – or cold – more recent initiatives in astronomy and oceanography are bringing citizen science opportunities to your phone or computer. The Globe at Night project, based out of the American National Optical Astronomy Observatory (NOAO), collects photos from volunteers to measure night sky brightness – and light pollution – around the globe. The University of Victoria’s NEPTUNE Canada project has a Digital Fishers website, where volunteers can help analyze deep-sea video 15 seconds at a time to identify fish, critters and geological features.

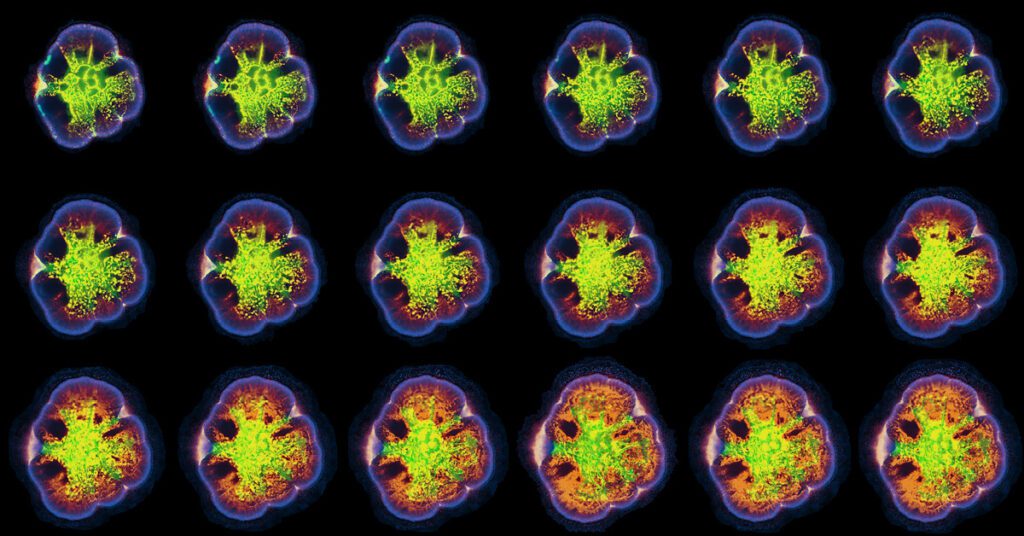

The best citizen science projects have a relatively straightforward and easy to understand research question, are very clear on the data required to help answer that question, and connect with specific communities who would be keen to get involved. Dr. Masaki Hayashi’s Groundwater Connections at the University of Calgary, for example, brings landowners in the Rocky View County region of the Alberta foothills into a community-based groundwater monitoring network. Dr. Hayashi wants to understand how water moves through the Paskapoo geologic formation, an aquifer that extends from the Rocky Mountain foothills east to the Calgary-Edmonton corridor. Instead of drilling a series of new groundwater wells, he’s using those that are already in place for residential and agricultural use. At the same time, he’s bringing residents together to better understand what’s happening with the aquifer from which they draw valuable water, and is benefitting from their personal observations.

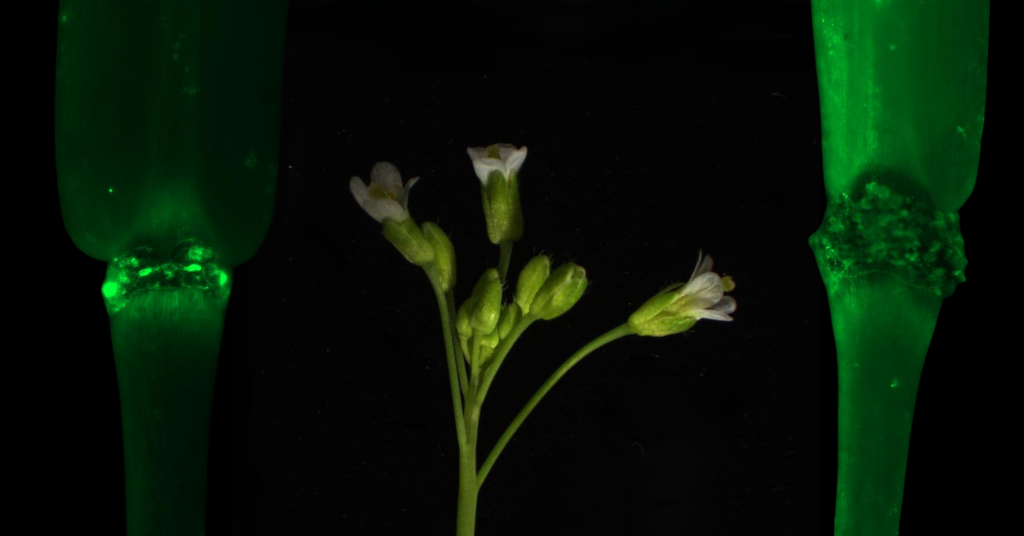

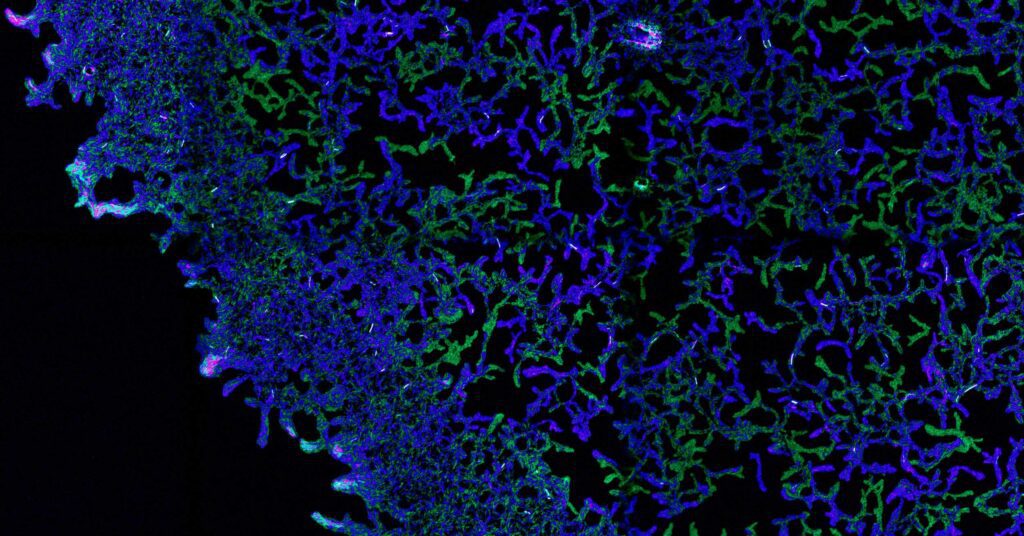

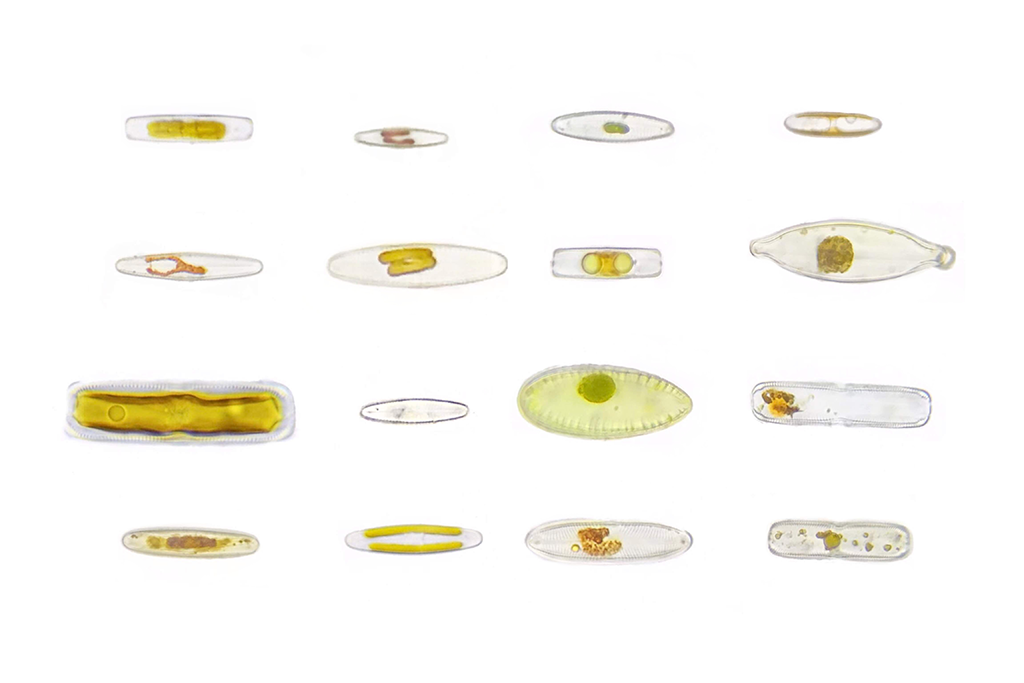

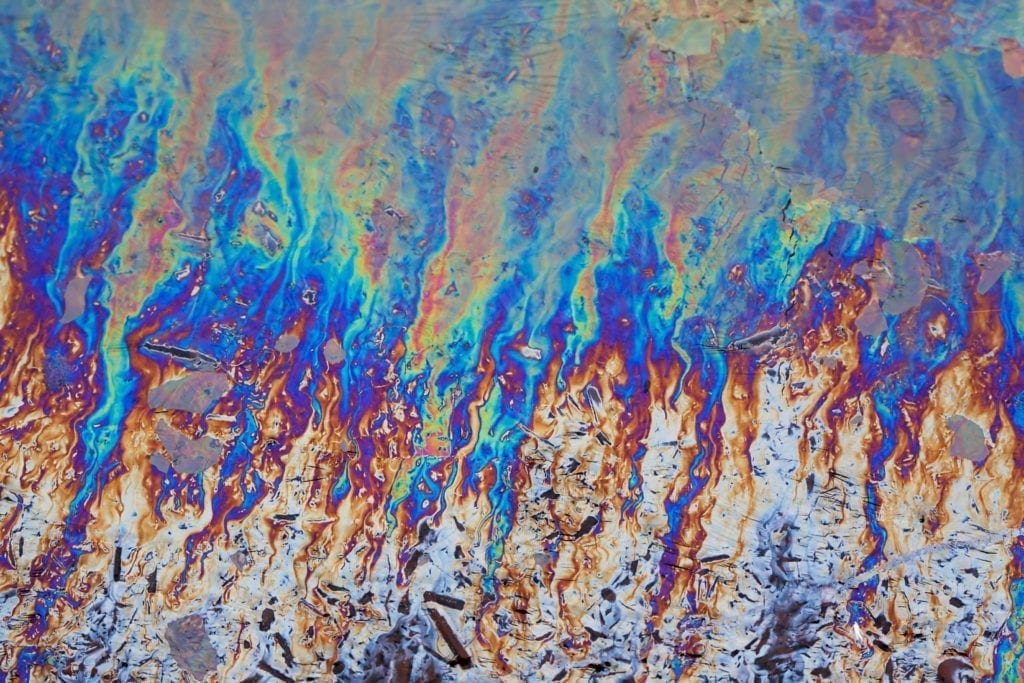

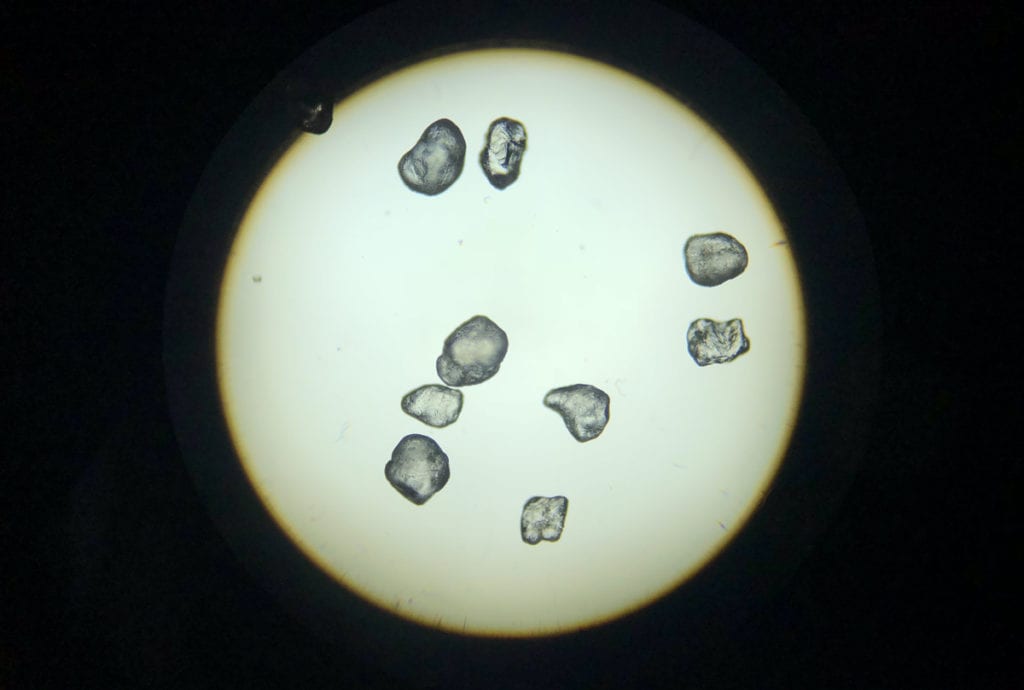

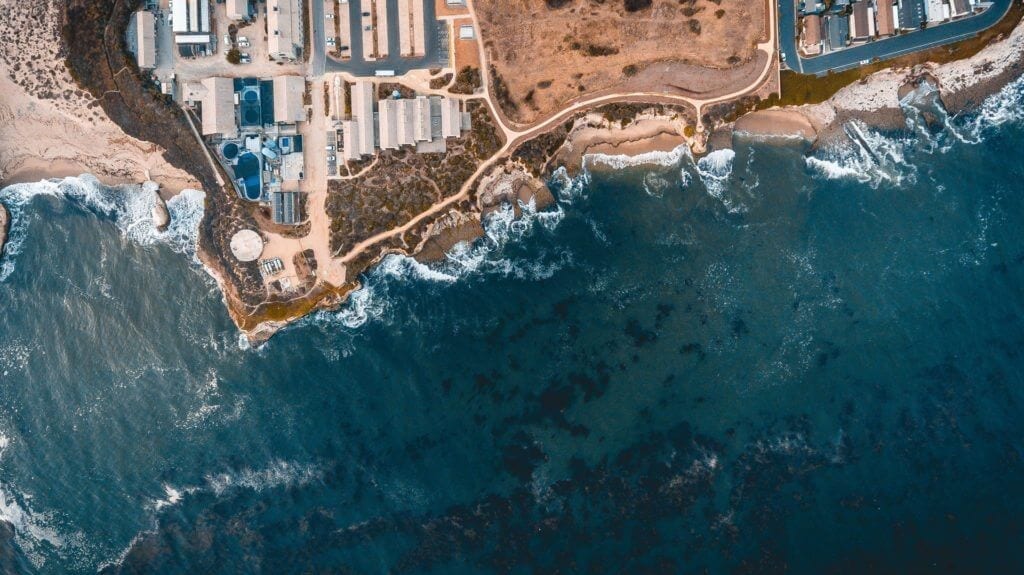

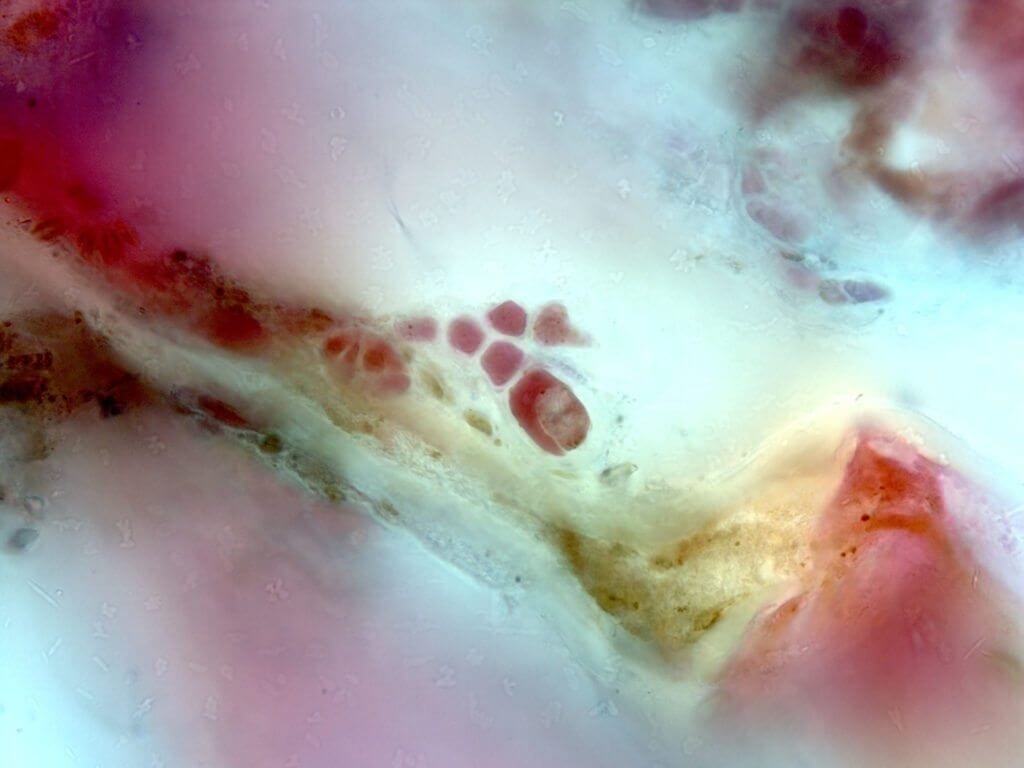

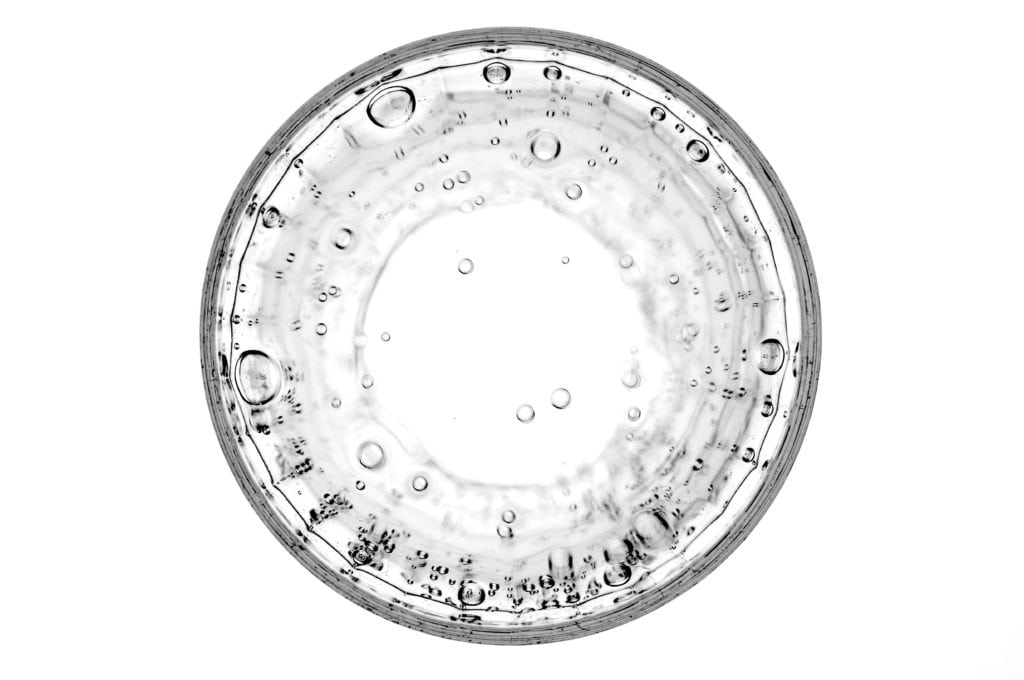

Citizen science can be a key component in monitoring and managing invasive species. Dr. Erin Cameron, an ecologist formerly based at the University of Alberta, has launched the Alberta Worm Invasion Project, which focuses on this invasive species in Alberta’s northern forests. She’s tapped into the Alberta angling community(who use worms as bait) as well as the junior high science curriculum, to map earthworm extent and inform Albertans about why the worms are bad, and how they can help prevent more ecological damage. On the other side of the country, Carole-Anne Gillis, a PhD student at Université de Québec, relies on citizen scientists to help monitor Didymo (also called rock snot) in the Restigouche River watershed. This invasive algae is not only aesthetically unpleasant, but can also affect Atlantic salmon populations.

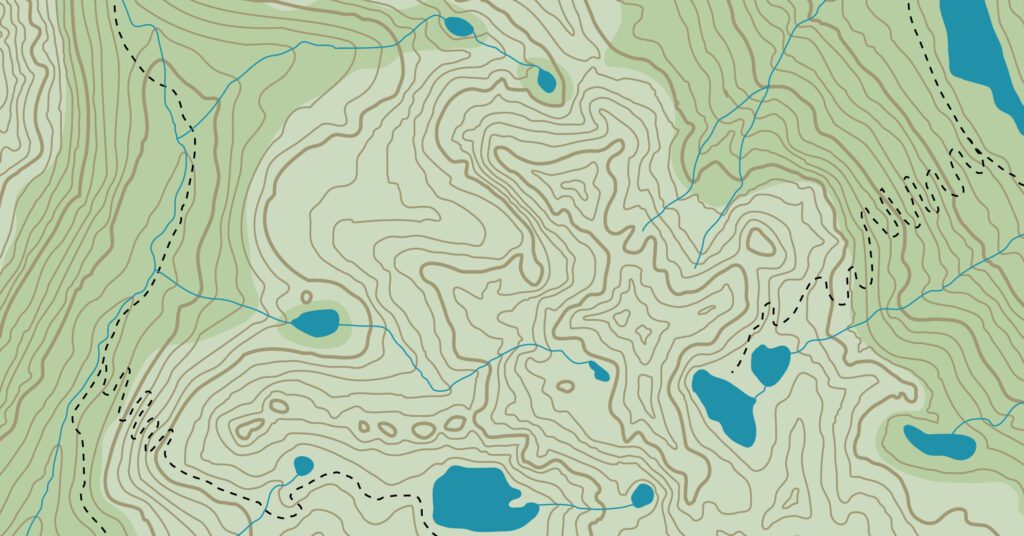

The key to citizen science isn’t just crowdsourcing data. It’s a two-way street, with a shared goal to engage citizens and increase their awareness of the world around them. The best way to do this is to make the research results accessible, so contributors can see how their data collection is helping, and what big picture is being revealed. RinkWatch, for example, has a page of maps and graphs, everything from the length of the 2012-13 season at outdoor rinks across the country, to a ranking of participating rinks by the number of data points each has submitted.

Their site also communicates in a jargon-free way: note that the data page is labelled ‘fun stuff’ rather than ‘maps and graphs’. The citizen scientists involved in this project are part of a national network, connecting them to a larger community to which they’re contributing with their individual observations.

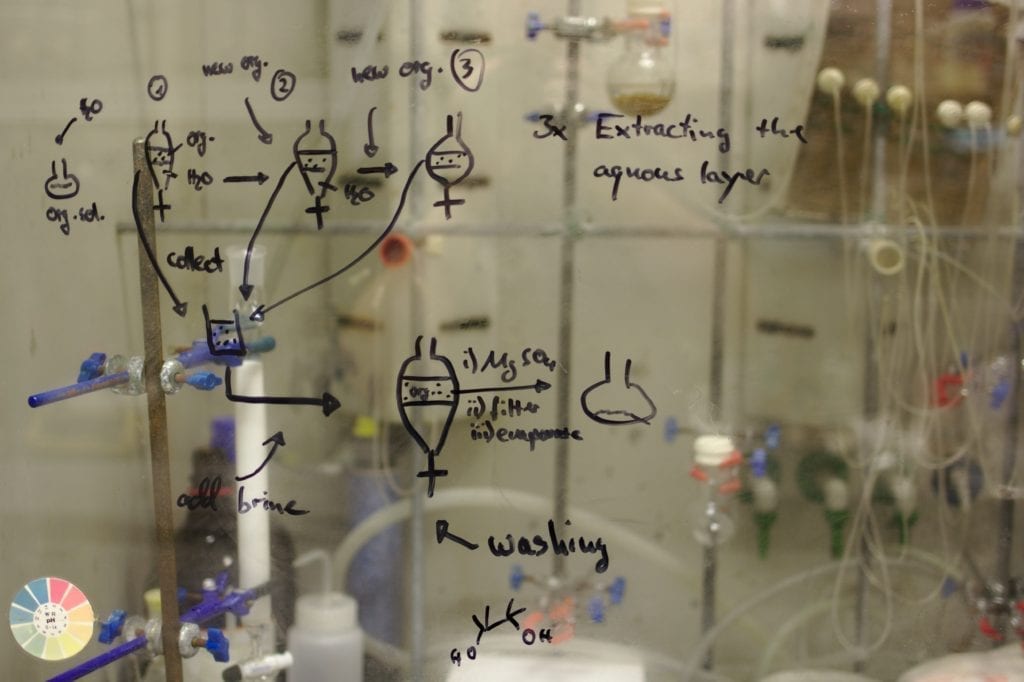

One of the challenges lies in assessing data quality. Andrea Wiggins and her colleagues found that citizen science projects address this issue in a range of ways, including supplementing online data submission with hardcopy data sheets, which allows participants to include comments that are difficult to format online; requiring a photo along with data submission; expert review of data; and requiring citizens to log in before submitting data.

It’s also important to ensure to pay attention to ethical considerations in citizen science. In Dr. Hayashi’s project, for example, the online map of groundwater well locations clearly states that they’re plotted within 800 m of their actual location, to preserve the privacy of the well owners.

Interested in joining a citizen science project? A quick search of Canadian projects on the Scistarter citizen science site includes not only the RinkWatch and Digital Fishers programs, but also deforestation mapping, community aquatic monitoring, and more.

Looking to put together your own citizen science project? Check out some of these resources:

- Dickinson JL, Zuckerberg B, Bonter DN. 2010. Citizen science as an ecological research tool: challenges and benefits.Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 41: 149-172.

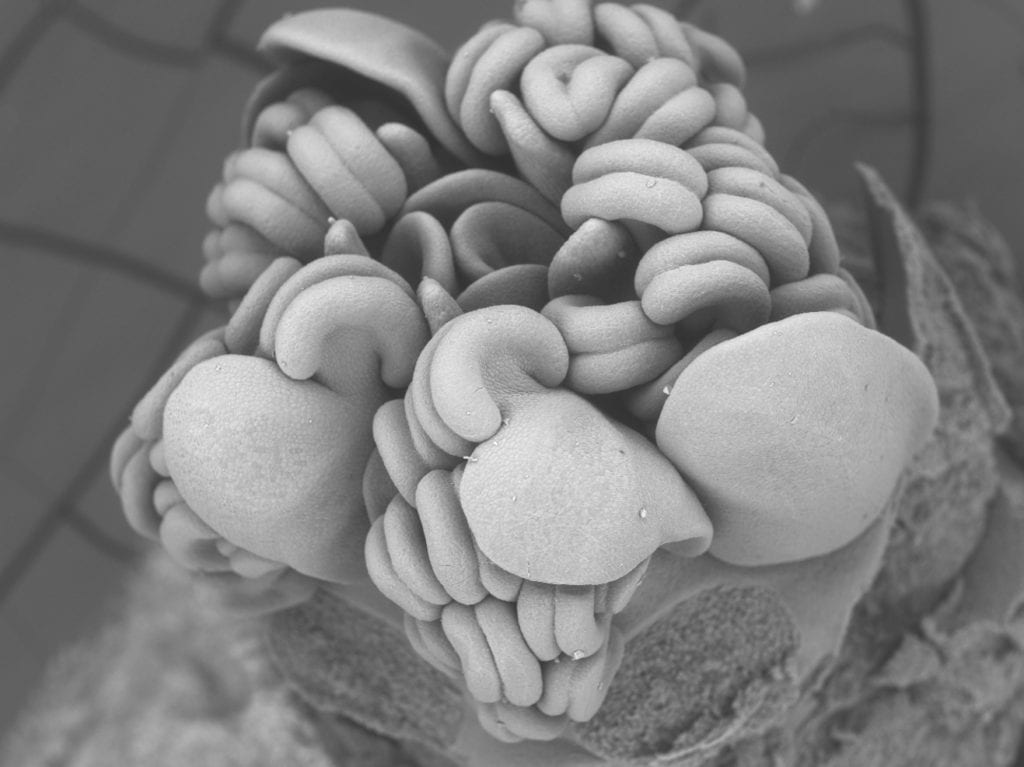

- Kremen C, Ullman KS, Thorp RW. 2011. Evaluating the quality of citizen-scientist data on pollinator communities. Conservation Biology25(3): 607-617.

- Wiggins A, Newman G, Stevenson RD, Croston K. 2011. Mechanisms for data quality and validation in citizen science. “Computing for Citizen Science” workshop at IEEE eScience Conference. 6pp.