You’d think I was plotting to kill and eat Bambi.

“Why would you do that?” they said. “Leave it alone.”

My colleagues at the National Research Council (NRC) were troubled because I had contested the legitimacy of our “Newton Apple Trees.”

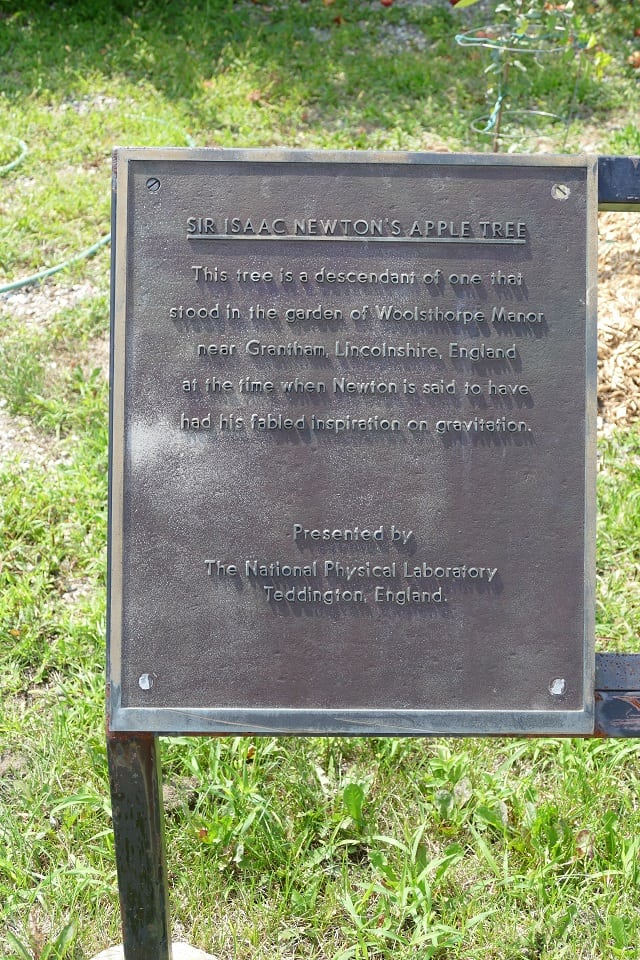

Next to the NRC measurement science labs in Ottawa (Building M-36), these two small trees bookend a bronze plaque identifying them as descendants of the one that dropped an apple in the garden at Woolsthorpe Manor, Lincolnshire and inspired Sir Isaac Newton 350 years ago.

The plaque makers had good reason to believe the words they were engraving. The trees were the product of authenticated graft material provided in 1961 by the National Physical Laboratory (NPL) in Teddington, England, and the story of Newton’s falling apple, although mythic-sounding, has roots in contemporaneous accounts of words spoken by the great physicist. In 1727, the year of Newton’s death, Voltaire reported without qualification, for example, that “the fall of an apple from a tree suggested (to Sir Isaac) that the force of gravity, which made the apple fall, was also the force that kept the moon on its path.”

The NRC trees accordingly have induced smiles and feelings of pride over the years, and the gift to Canada of the Newton tree strain has been celebrated in a few apple pie feasts. On occasion, seeds or leaves were embedded in mementos or retirement gifts, and this practice inspired the project that eventually caused us to question the pedigree of our trees.

This year, 2016, marks our centennial at NRC, and we have celebrated the milestone in a number of special events. And like many centennial-celebrating entities, we are preparing a coffee table book to share our history and some of our stories.

It will be informative, photo-filled, odd-sized, and coffee-table heavy.

But in a world now flooded with too-easy-to-publish books, we face a challenge in trying to make ours stand apart. Our strategy for confronting this task was built around the idea that our book should be the embodiment of innovation as well as being “about innovation.” The scheme called for the imbedding the physical book with a piece of technology that hinted at the future along with an artefact that touched the science of the past.

Though there were many ideas for making our book physically futuristic, from the beginning, only one idea was discussed when it came to making our centennial book an artefact of science past—a seed or a leaf from our Newton Apple trees—thus DNA material traceable to one of the great moments in science history. It seemed like an easy idea to implement. The book designers started work, and we started talking up our great idea.

Most people reacted positively, but a few asked awkward questions.

“Didn’t that NRC Newton apple tree die?” “Wasn’t it replaced by a Canadian tree?” “Wasn’t that story some kind of legend?”

After reading a public, third-party report of the death of our original tree, I became concerned and was haunted by visions of touting out leafy books only to find out that the leaves or seeds were frauds.

I began to research the heritage of our trees. The NRC correspondence records didn’t contain much. So, I checked respected sources online starting with the National Physical Laboratory, Kew Gardens, British universities, and other institutions claiming Newton trees.

It’s not too hard to find stories about the original Newton tree and to find a lot of points of debate about its precise location in the Woolsthorpe garden, its lifespan, and its living descendants. A particularly vigorous effort to document the evidence can be found in the pages of Contemporary Physics in a 1998 article written by Dr. Richard Kessing. He has to be the person who cared about this issue the most and was convinced not only that descendants of the Newton tree exist, but that the original tree itself survived all forms of mishap, weather, and human abuse to endure to today.

Scholarly skeptic Alberto A. Martinez, author of Science Secret: The Truth About Darwin’s Finches, Einstein’s Wife, and Other Myths, figuratively rolls his eyes at this thought.

But skeptics and enthusiasts agree on a few points.

Enough written evidence exists to convince most that Newton often told the falling apple story to others, that sincere people believed that they knew which specific tree was the one responsible, and that efforts were made to ensure the progeny of that tree survived. The majority also agree that the famous tree was the rare variety “Flower of Kent” and that the Fruit Research Station, an agricultural institute at East Malling in England, has a firmly accepted, living relation. The East Malling stock was derived from material originally collected in Newton’s garden around 1820 by the Rev. Charles Turnor, a member of the family that owned Woolsthorpe Manor virtually from the time of Newton’s death to its transfer to the National Trust in 1980.

It turns out East Malling Research Station has a DNA analysis service. I contacted them earlier this year, and they gave me a deal for testing our tree DNA. In early May, a dozen leaves from our trees were wrapped in refrigerated wet paper towels and put on a plane for England.

Weeks passed and no word. In the meantime, more records came my way from the NRC Archives. We found a 1961 letter about our original tree from the NPL’s head Sir Gordon Sutherland to NRC President Steacie. The letter is particularly poignant as it included a hand written note referring to Ned Steacie’s health. The revered NRC President would die of cancer within the year. NRC evidently valued the NPL gift as real and sent a small maple tree to Britain in return.