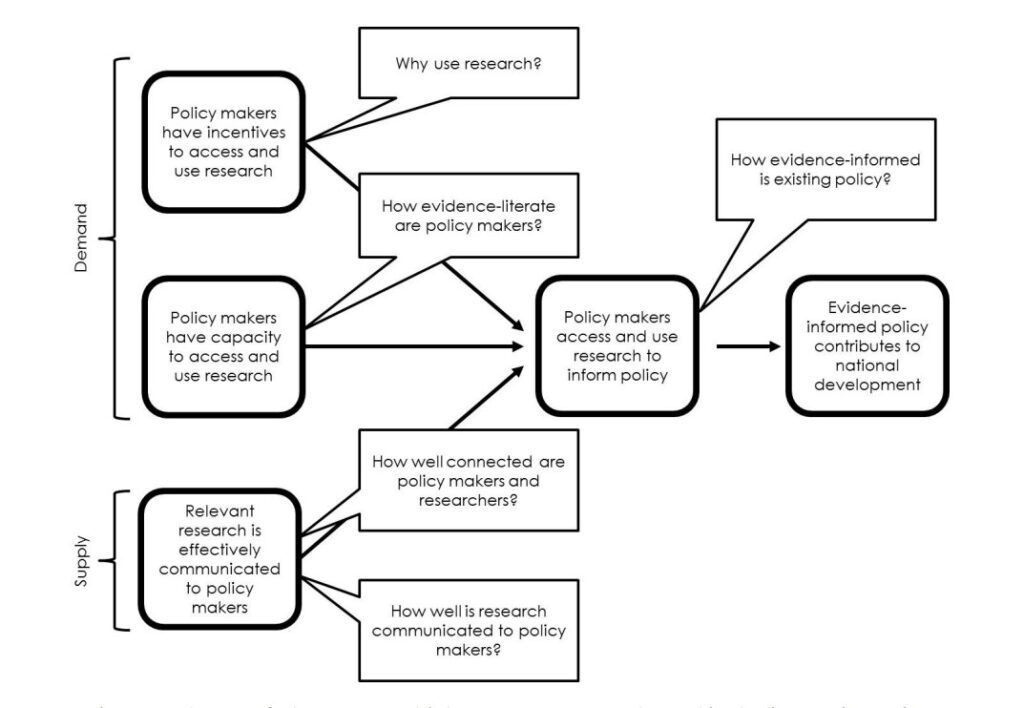

The days of research staying within the walls of “the ivory tower” are over. Today, research communications aren’t just about education and engagement, building trust, or funding support. Good communications are also about supporting decision-making.

Understandably, decision-makers are unlikely to keep an eye on all the latest research, nor will they fully understand the terminology, nuances, or even the statistics presented in peer-reviewed papers. After all, peer-reviewed publications are, first and foremost, a way to communicate with specialists in a particular field. For those researchers who want to connect with decision-makers, a briefing note may be just what they need.

“Briefing notes serve to provide important information to decision-makers, be they senior leadership and managers, or policymakers internally, or to politicians externally in a short, digestible format,” explains Dr. Victoria Metcalf, subject editor with FACETS and Principal Advisor – Stakeholder Engagement at the Ministry of Education Te Tāhuhu o te Mātauranga in Wellington, New Zealand.

“How briefing notes are shared with decision-makers depends on the governmental system in a country,” says Metcalf. “They might be commissioned directly through something like an expert committee straight to parliament or local government body; requested by a government department seeking to understand an issue to then design policy; or you might be asked to contribute information to one that a government department or official committee is writing themselves.” Equally, “A professional body, such as a marine sciences society, might prepare one in response to a call for submissions on a topic. Finally, a professional body, organisation or individual(s) may create one because they want to alert decisionmakers to a threat, challenge, or opportunity in a cold call scenario,” Metcalf adds.