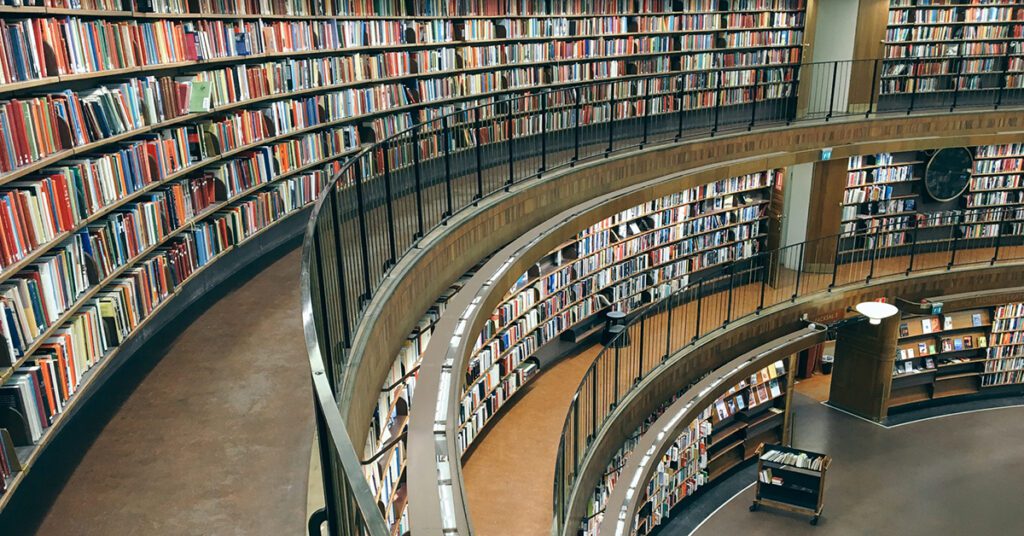

Researchers are well aware of the importance of understanding how their field has developed over time, and where their research fits into that broader context. We don’t want to reinvent the wheel, but we also don’t want to miss potential opportunities where there are research gaps.

In previous posts we’ve discussed several ways to put your current research in context: considering your academic genealogy, for example, and how scientific ideas have percolated through the generations of that family tree, or reading seminal papers in your field that were published before the current science publication boom.

There’s another approach, however: delving into the history of your discipline. This can give you a sense of how the discipline has developed over time, its place in society and scientific thought in general, and the key players that have helped move the field forward.

In 2009, I attended a talk by US scientist Dr. Matthew Sturm at the American Geophysical Union (AGU) Joint Assembly in Toronto. As a newly-elected Fellow of the AGU, he’d been invited to share the highlights of his career to date. But rather than recite a litany of all the contributions he’d made to the field of snow science—particularly in Arctic regions—he talked instead about how to recruit students to do polar research. His idea? We should share the history of Arctic research with students so they could see how exciting it was and get engaged from the beginning.

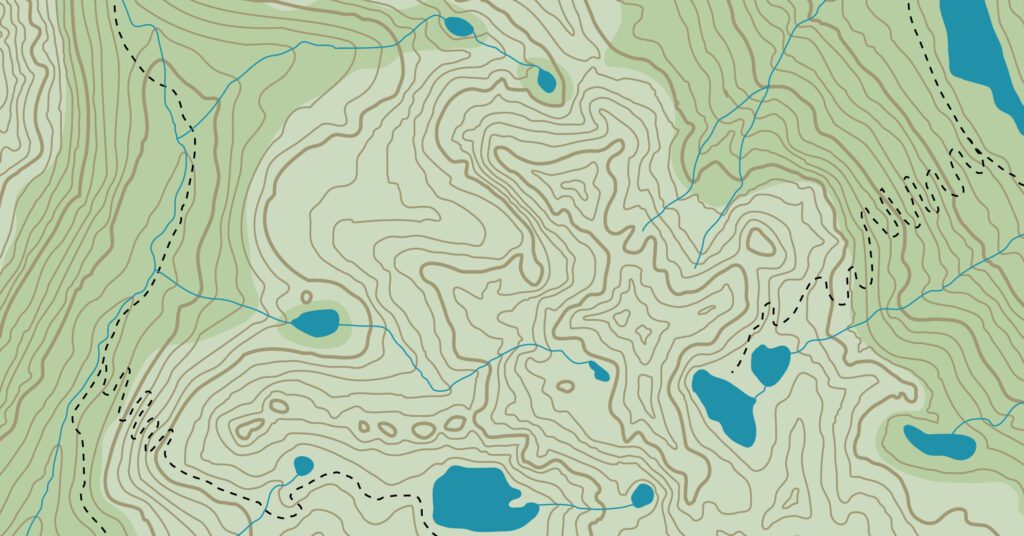

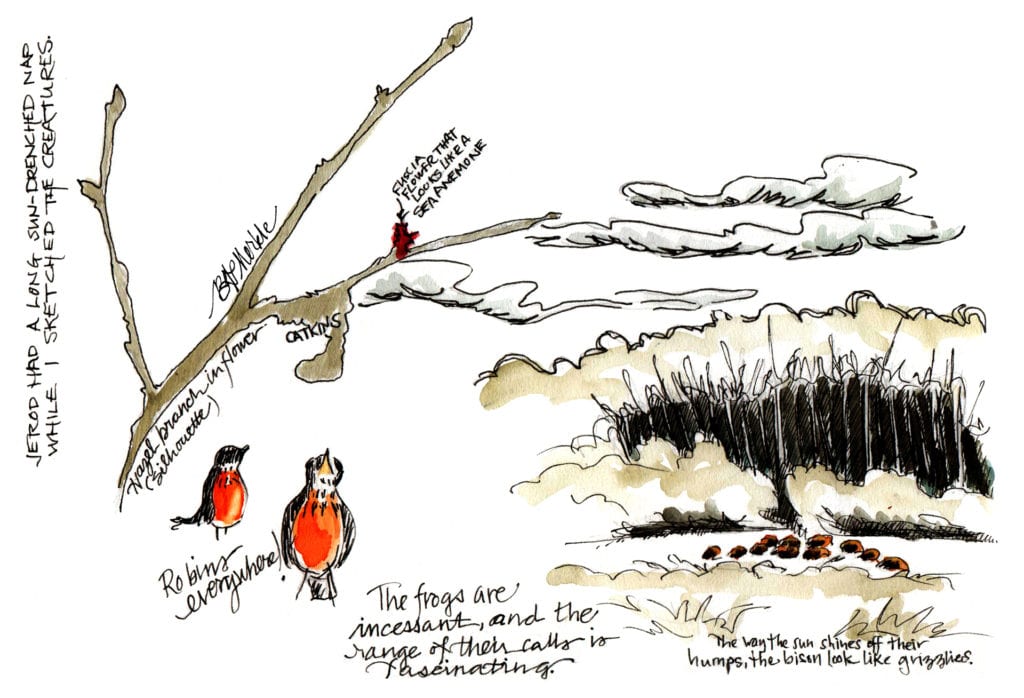

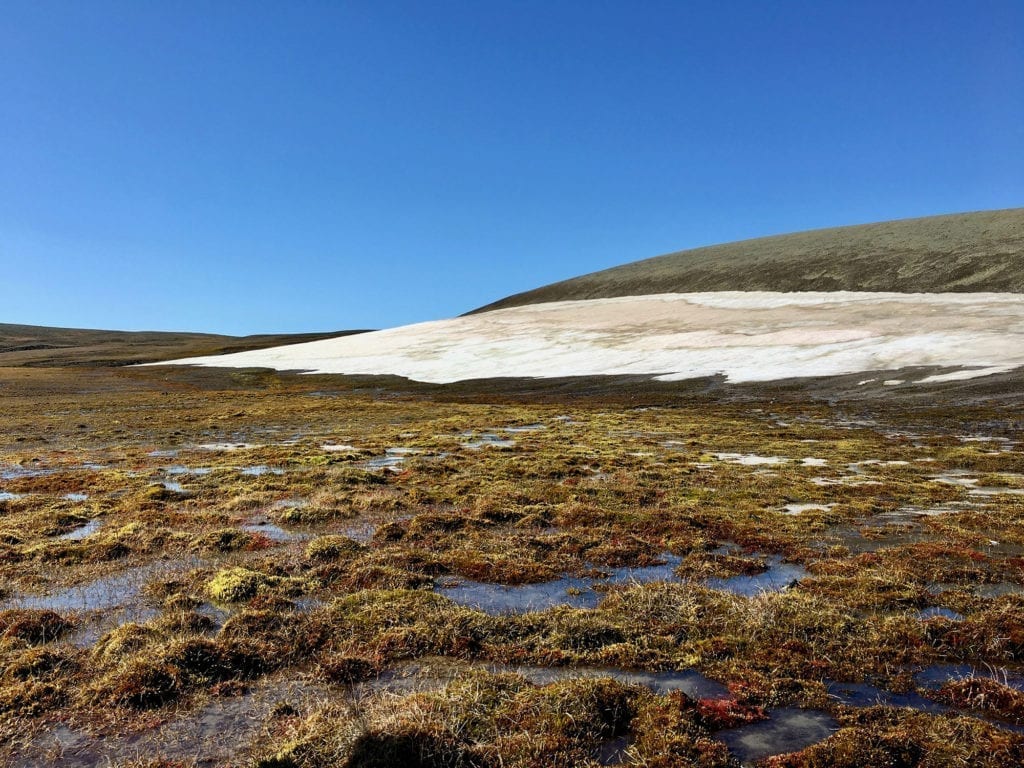

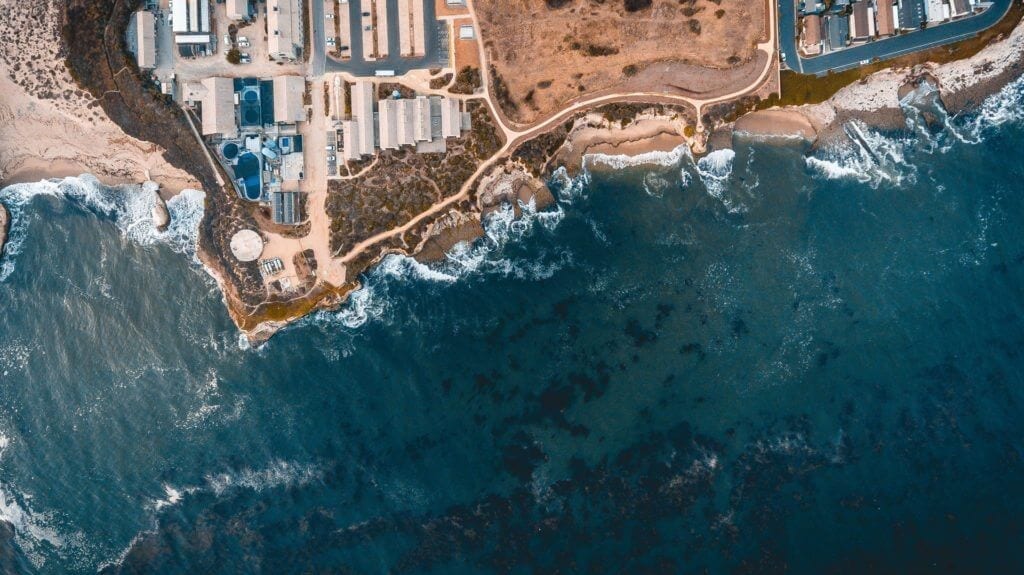

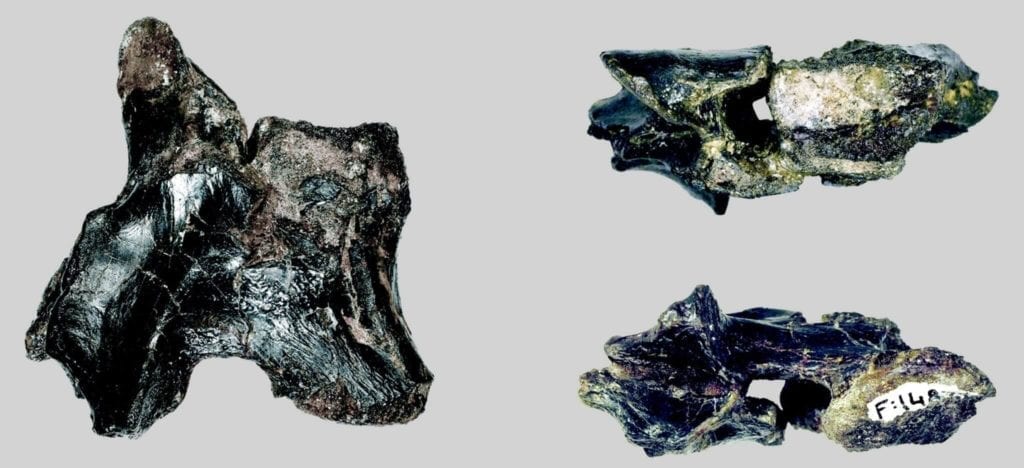

Much of Sturm’s talk rang true to me. During my PhD, I spent three summer field seasons in Canada’s Arctic. Most of the people I met at the Polar Continental Shelf Project’s (PCSP) field station in Resolute Bay had read—or were reading—various histories of the Arctic. A favourite was Pierre Berton’s The Arctic Grail, an account of the explorers who had ventured into the Arctic between the early 19th and early 20th centuries. These men (for they were all pretty much men) were scientist-naturalists: exploring new terrain, but also collecting scientific data such as weather and sea ice observations to take back to their home country.

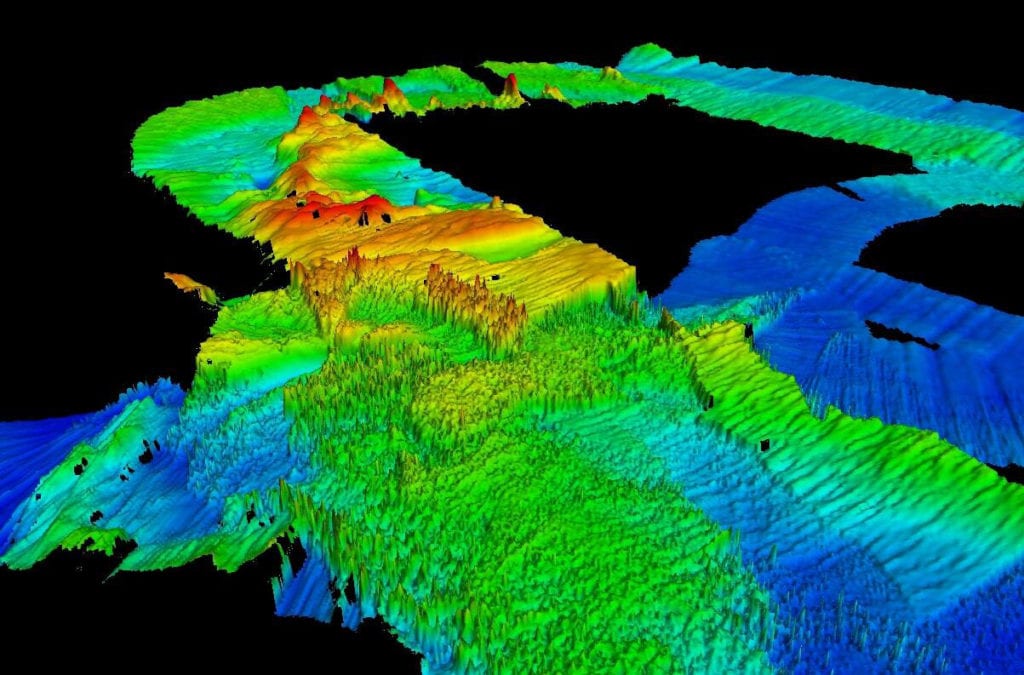

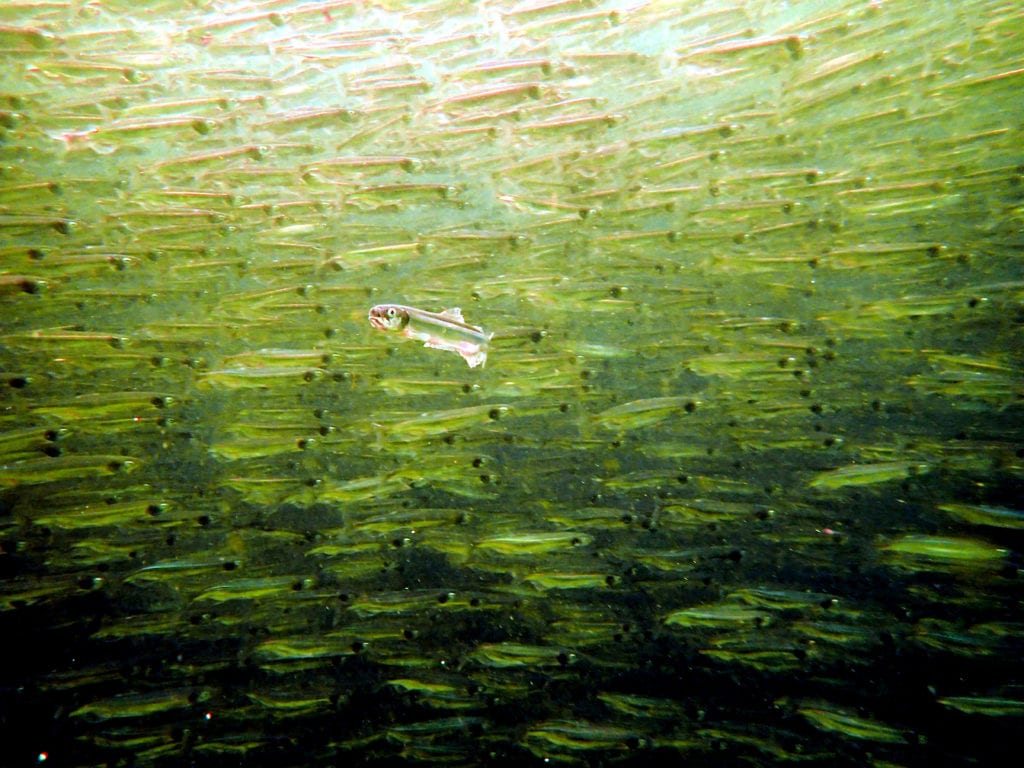

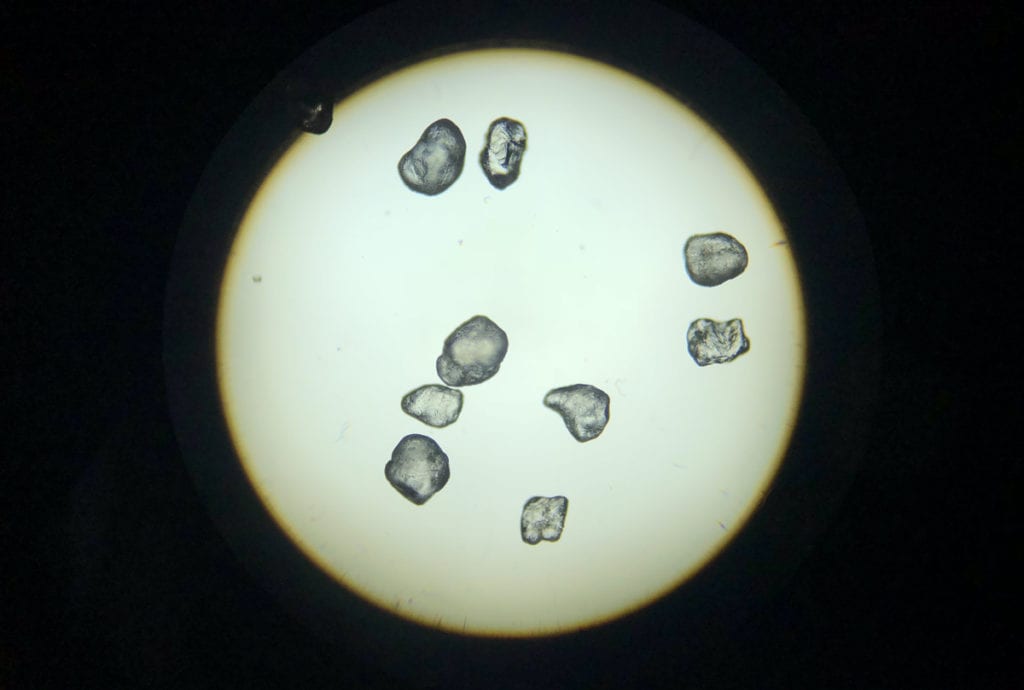

We read these books not because they’d point us in the direction of key scientific papers, but because they represented the fascinating history of our field. These explorers had made scientific measurements with far less sophisticated instrumentation than we had, and had survived in much less comfortable conditions than we did. In many cases they’d made critical discoveries, like Fridtjof Nansen’s mapping of northern ocean currents.

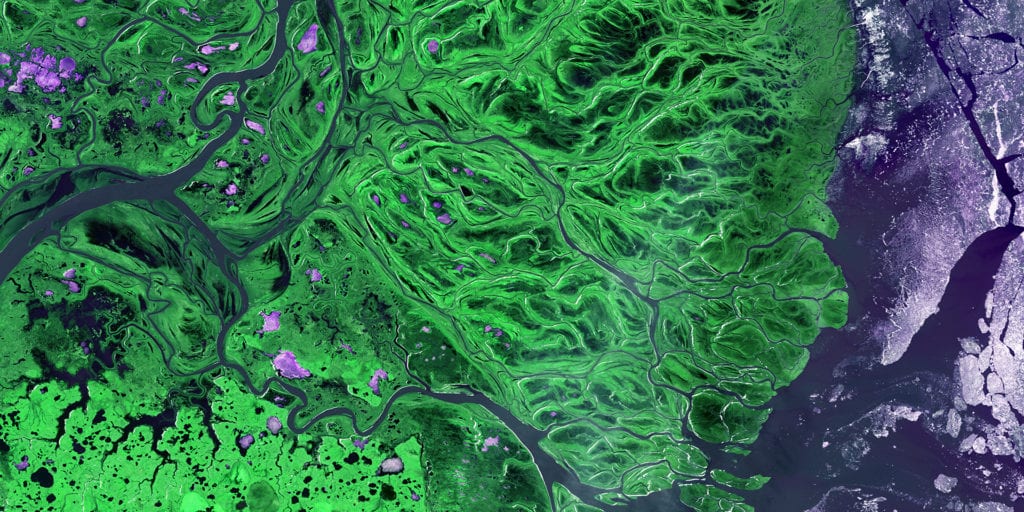

We were also interested in the early years of Canadian Arctic research: the 1950s to late 1960s, which marked the beginning of Arctic research programs at both PCSP and McGill University. Some of the scientists who worked for these programs, like the Geological Survey of Canada’s Fritz Koerner, were still around when we started our careers. They had loads of stories to tell, including the switch from dog sled teams to skidoos, the conditions on a particular ice cap in a specific year, and other anecdotes about data collection or analysis that never made it into their published papers.

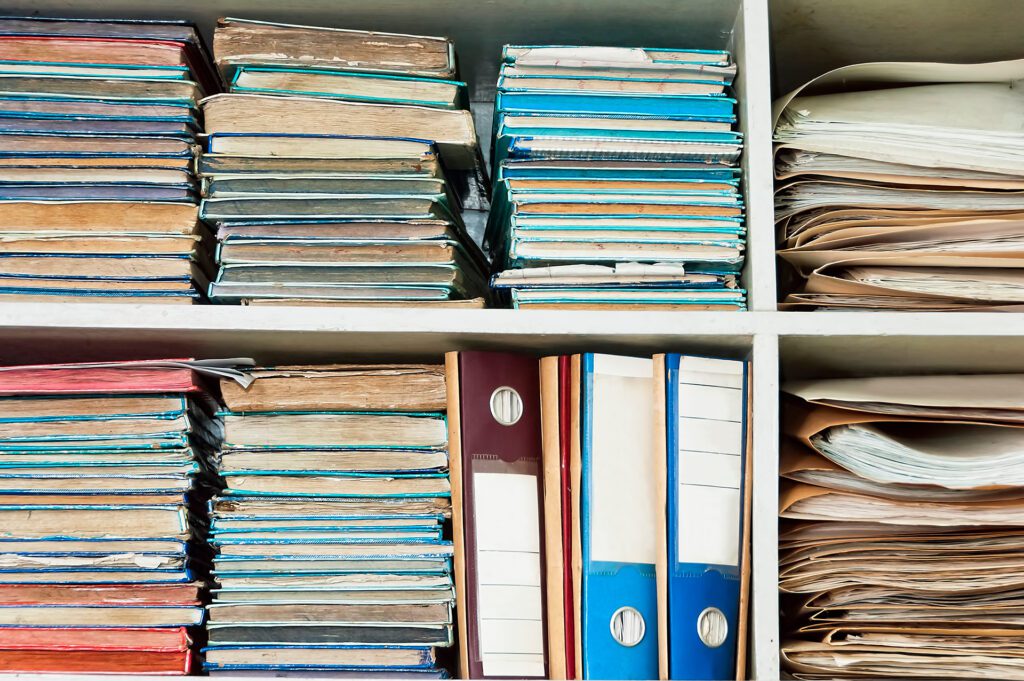

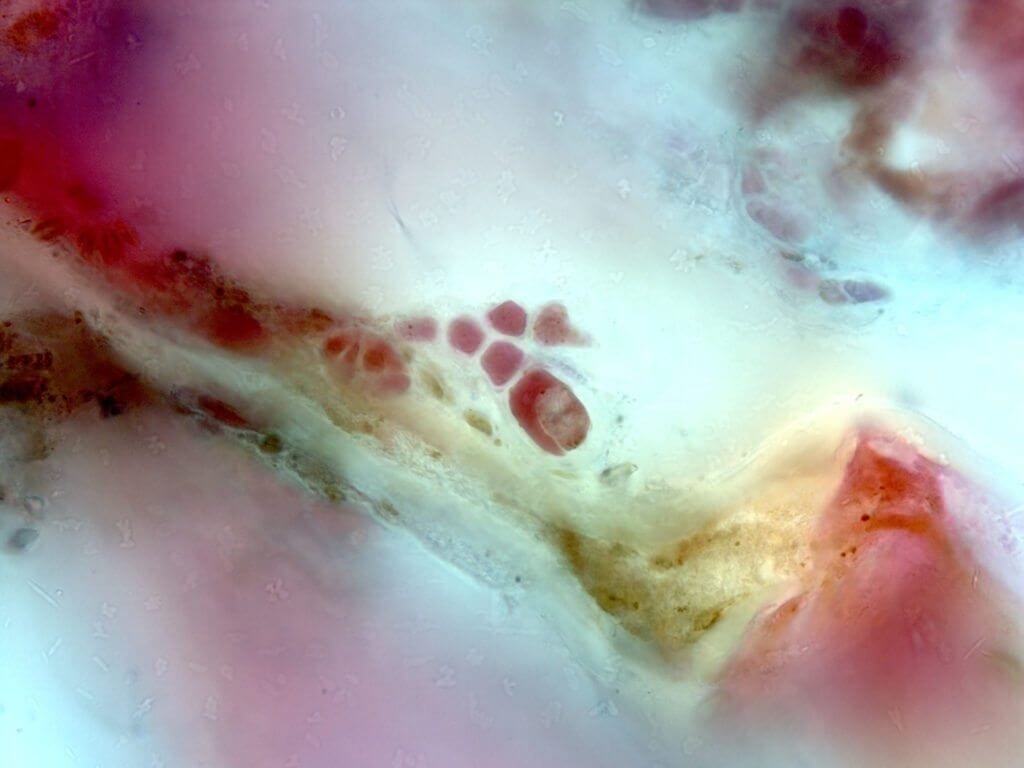

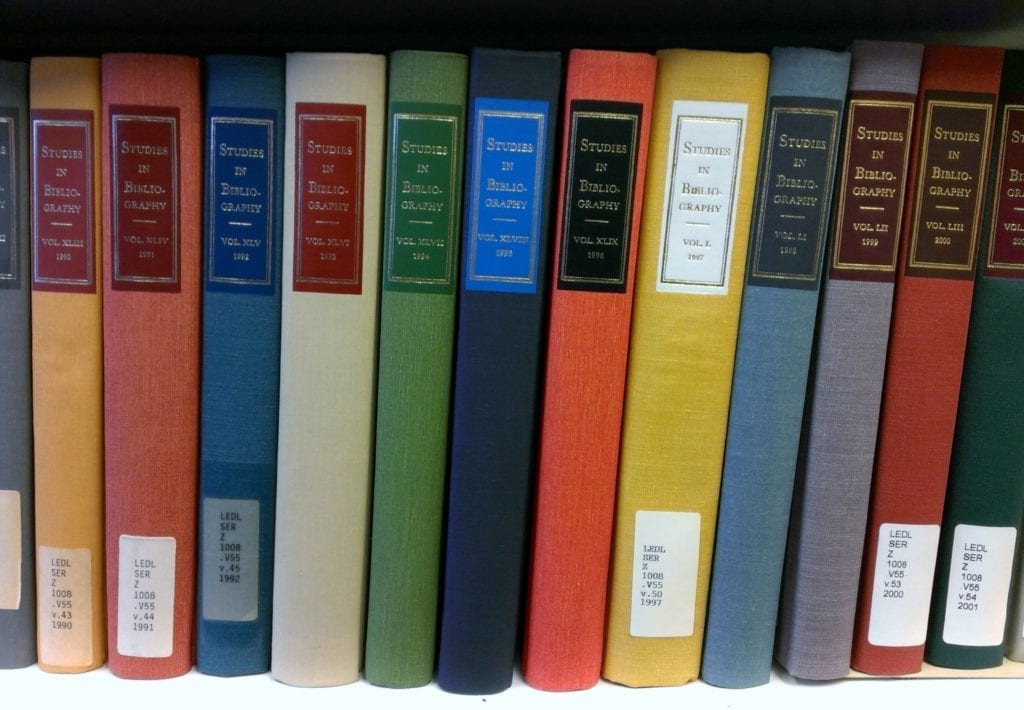

As these researchers have passed away, we’ve lost their lived experience of the Arctic. What we do have, however, are accounts of their research in the Arctic Institute of North America’s journal Arctic, which summarized the work of the Devon Island Expedition annually from 1961–1973. It’s fascinating reading that shows how a fledgling research program expanded and gained credibility over a relatively short time period, developing new research ideas and building on its progress each year.

These are the stories that give you the long view on your research field—and can provide a bit of excitement about and engagement with those early days of exploration. And if you’re moving between disciplines, you can always find a book to help you understand the history of your discipline. When my research shifted more into forest hydrology, for example, I read The Hidden Forest, on the history of research at the HJ Andrews (HJA) Experimental Forest in Oregon. It provided a picture of how the experimental forest network developed in the United States, and the contributions that HJA researchers had made to that network.

Whether you’re working in BC’s Coast Mountains and have read about the extensive mountaineering explorations of Don and Phyllis Munday, or you’re studying Greenland’s climate history and have read historical records from Dutch whaling ships, try to make time to read about the history of your research field. It can also be a way to fit in some reading for pleasure, instead of reading purely for work!