In this series, we’re sharing practices of community-engaged research (CER): researchers and community partners working together to advance community goals and science.

Taking time to learn: New author resource for community-engaged research

“…meaningful research…”

“…address the community priorities…”

“…a shared learning experience …”

These are the words of Leigh Joseph, an Indigenous ethnobotanist at the University of Victoria. She uses these words to describe research on renewing connections to cultural knowledge of plants in her community, the skwxwú7mesh First Nations in British Columbia, Canada.

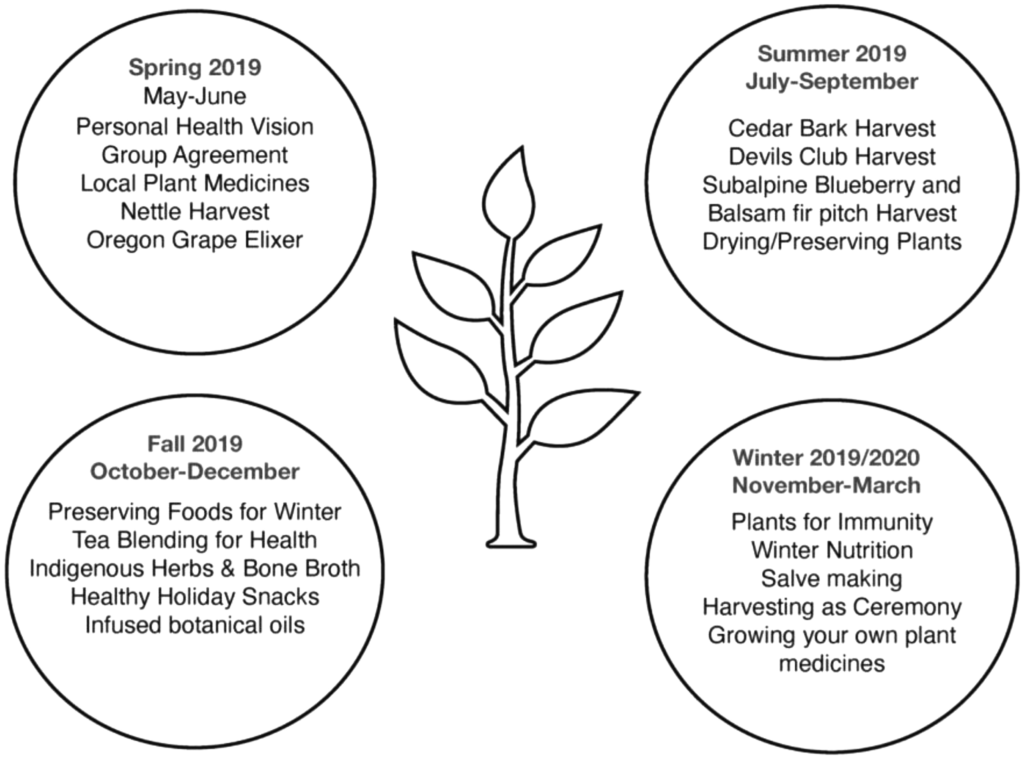

As part of her doctoral studies, Leigh worked with the skwxwú7mesh First Nations community to create a “land-based and hands-on program to learn about and reconnect to culturally important plants.” The community was involved at every step of the research, including identifying the community goal, co-creating research activities, and collecting data with plant harvests.

Examples of activities created for the skwxwú7mesh First Nations community-based program.

This project is an example of community-engaged research (CER), which involves researchers and community partners working together to advance community goals and science. Increasingly, advocacy groups, academic institutions, and research funders are creating guides on the key practices of CER, including dissemination of the results.

One way results are disseminated is with peer-reviewed publications in journals, but there is little guidance for authors on how to report CER in scientific papers.

New guidelines for reporting community-engaged research in manuscripts

As a publisher of CER, Canadian Science Publishing (CSP) felt strongly that we should provide authors with guidance on how to responsibly and transparently report research that involves the participation of community members.

We consulted with researchers and community partners to create guidelines for authors reporting CER so that authors would have access to best practices for reporting on community engaged research in articles.

We also introduced Community involvement statements to give authors the option to concisely state how the community was involved in the study and how the study benefits the community.

“Researchers who spoke with us expressed gratitude for community partners and a desire to acknowledge their contributions in a meaningful way within the article,” says Melanie Slavitch, Peer Review Manager at CSP. “So while these guidelines are about transparent reporting, they’re also about creating space to honour the relationships, learning, and real-world impacts that can characterize CER.”

The guidelines provide:

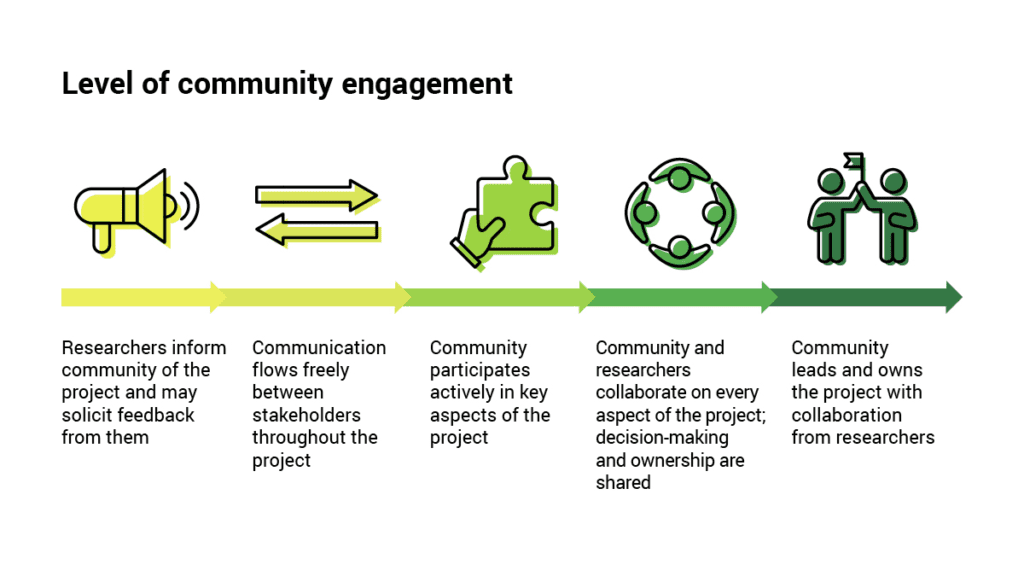

- definitions and descriptions of the spectrum of community involvement,

- key features of CER to consider before, during, and after a project is complete, and

- content to consider addressing in the manuscript (e.g., Why is the research question important to the community? How was the community partnership established?)

“Encouraging authors to fully describe the processes taken to complete CER normalizes open sharing of how research happens in partnership with communities,” says Dr. Lisa Loseto, Co-Editor-in-Chief at Arctic Science. “It is important for publishers to provide and build a safe space for those involved in CER to report their work in this way. Open sharing of all study components increases transparency and will strengthen future projects and the publication of them.”

NOW AVAILABLE

Community-Engaged Research Collection

Open conversations lead to inclusive publishing practices

These guidelines arose from a perspective paper on re-Indigenizing conservation. The lead author is M’sɨt No’kmaq—Mi’kmaw for “all my relations.”

“The Mi’kmaw concept of M’sɨt No’kmaq represents a kin-relationship with the land, waters and all living beings…We have chosen M’sɨt No’kmaq as lead author to honour the collective and to acknowledge that all stories, learning, and language come from the land,” explain the co-authors.

Prior to submitting their paper to the journal, the authors and editorial teams at CSP had conversations about including M’sɨt No’kmaq, a more-than-human entity, as an author. Given our ongoing efforts in equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI), we embraced the opportunity to learn ways to respectfully attribute authorship of Indigenous knowledges.

After extensive research and consultation with Indigenous and non-Indigenous researchers and community partners, and many earnest conversations, our Publishing Policy now includes “more-than-human” as an option for attributing authorship.

During this research phase, we noticed that the scholarly publishing industry lacked guidelines for reporting CER in manuscripts submitted for peer review.

Near the Peel River at Ernest and Alice Vittrekwa’s fishing camp, Tracey Proverbs (left) and Ernest Vittrekwa (right) measure broad whitefish as part of a monitoring project. | Photo by Arlyn Charlie

Near the Peel River at Ernest and Alice Vittrekwa’s fishing camp, Tracey Proverbs (left) and Ernest Vittrekwa (right) measure broad whitefish as part of a monitoring project. | Photo by Arlyn Charlie

Thinking more about engaging with communities

This post is the first in a series highlighting different aspects (e.g., data sovereignty) and different approaches (e.g., citizen science) of CER.

A key feature of CER is first taking the time to learn about the community—its history, culture, values, and goals. Then, rooted in mutual respect, is the building of mutually beneficial research relationships with researchers and community partners working together.

We hope this series and the guidelines help support learning and relationship building. Feedback on our efforts and current publishing practices are more than welcome. Please direct questions, comments, and suggestions to Rachel Pietersma.

We thank all the community partners and researchers who shared their knowledge and feedback with us throughout the development of the author resources and blog series.

Blog post written by Natalie Sopinka, communications specialist at Canadian Science Publishing.

For more information about the whitefish monitoring program, read the open access paper: The importance of continuous dialogue in community-based wildlife monitoring: case studies of dzan and łuk dagaii in the Gwich’in Settlement Area

Banner image by Rachel Edgar | Caption: In a population, differences between people can be enlightening. In the pandemic so much has been learned from how differently we react. Similarly, there is much to be learned from differences between individual cells. Each point represents a cell from lungs or blood, coloured by cell type. Highlighted cells express the gene ACE2 (the receptor for the SARS-CoV-2 virus), putting them at higher risk for infection and the whole system in danger. Like knowing which people are vulnerable, finding cells at risk leads to understanding disease, protecting susceptible cells and protecting us all.

Examples of community-based programming full text

This infographic lists the activities of the land-based and hands-on program to empower Indigenous community partners to reconnect to culturally important plants. The infographic is displayed in four circles to represent the four seasons the program occurred during. Each circle lists different activities. The circles appear in each corner of the square infographic. In the middle of the infographic is the outline of a plant with leaves.

The first circle is entitled Spring 2019. Below this title is the text as follows: May to June, personal health vision, group agreement, local plant medicines, nettle harvest, Oregon grape elixer. The second circle is entitled Summer 2019. Below this title is the text as follows: July to September, cedar bark harvest, devils club harvest, subalpine blueberry and balsam fir pitch harvest, drying and preserving plants. The third circle is entitled Fall 2019. Below this title is the text as follows: October to December, preserving foods for winter, tea blending for health, Indigenous herbs and bone broth, health holiday snacks, infused botanical oils. The fourth circle is entitled Winter 2019/2020. Below this title is the text as follows: November to March, plants for immunity, winter nutrition, salve making, harvesting as ceremony, growing your own plant medicines.

Level of community engagement full text

This infographic entitled Level of community engagement lists and describes the different levels of community involvement for community-engaged research, often described as occurring along a spectrum.

Below the title are five icons arranged left to right. The left-most icon is a megaphone. The text underneath this icon is as follows: Researchers inform community of the project and may solicit feedback from them. The next icon is bidirectional arrows. The text underneath this icon is as follows: Communication flows freely between stakeholders throughout the project. The next icon is a hand holding a puzzle piece. The text underneath this icon is as follows: Community participates actively in key aspects of the project. The next icon is four people in a circle with arms outstretched to each other. The text underneath this icon is as follows: Community and researchers collaborate on every aspect of the project; decision-making and ownership are shared. The right-most icon is two people holding one flag. The text underneath this icon is as follows: Community leads and owns the project collaboration from researchers.