How should you present information in your paper? In the body of the manuscript? In a graph? A diagram? A map? An illustration?

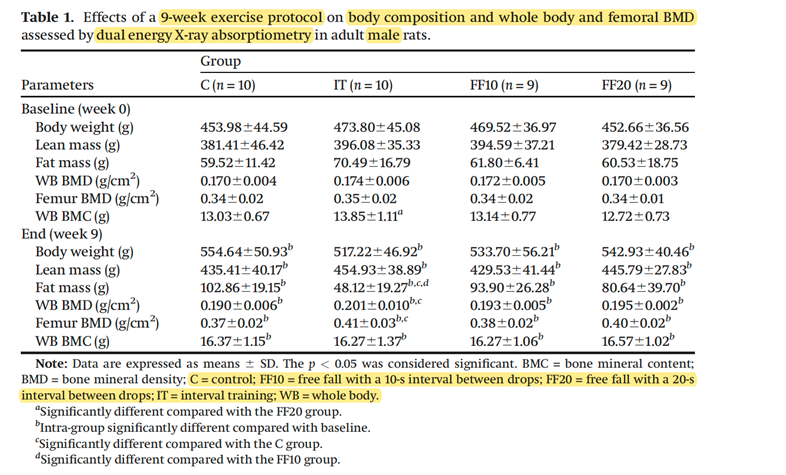

When it comes to data, tables are often the go-to choice.

Creating tables may seem like a relatively straightforward affair. However, the construction of a high-quality table is not easy. “I found it very difficult when I first started my career as a researcher,” says Dr. Brian Beres, Editor-in-Chief of the Canadian Journal of Plant Science. “You know the data and results intimately, but that doesn’t mean it’s simple to put them together in a table that readers can easily navigate and understand. Practice really does make the perfect table.”

If you’re looking for some tips to help you create a great table, you’ve come to the right place!