Peatlands are unique wetland terrains made up of an accumulation of decaying plants; they also cover over 1 million km2 of Canada. Don’t be fooled by these swaths of decomposing vegetation, peatlands provide essential ecological services such as capturing carbon dioxide and also contribute to increasing regional biodiversity. In addition to finding an array of bird species in peatlands, you can also find an abundance of orchids, including rare and endangered species. Peatlands make excellent stopover sites for migratory birds with ~6,000 insect species for them to feed on.

While over 1 million tons of peat are harvested and sold each year, successful restoration programs help to offset negative impacts from intensive harvesting. In order to ensure successful and responsible restoration, we need to know what pre-harvest, undisturbed peatlands look like; to get the full picture researchers rely on modern-day data and also travel way back in time.

Peat of today and peat of yore

To best understand the make-up of an undisturbed peatland, Université Laval researchers from the Peatland Ecology Research Group (PERG) reconstructed the 8,000-year history of a peatland near the St. Lawrence River (Québec, Canada). In their recently published study in Botany, the researchers took peatcores—imagine putting a giant straw into the ground and pulling up a tube-shaped piece of dirt with the age of the dirt being oldest at the bottom of the tube and youngest at the top—and identified which plant species were present in different layers of the cores.

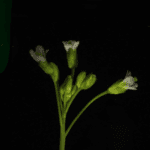

“The coring in the field is a fast process,” says Vicky Bérubé, lead author of the study and PhD student with PERG, taking only hours in comparison to “the preparation of samples, identification and counting of the fossil pieces,” which can take weeks to complete. Each layer of the core is passed through a sieve. “You obtain thousands of little pieces that you have to classify. Some cannot be identified because of they are too decomposed or they are missing some important characteristics required to confirm the taxa, sex, or species,” Bérubé adds. When the researchers came across a fossil they recognized, such as a fragment of a leaf or dried fruit or whole plant seed, there was still a thorough investigation to confirm the identity of the fossil. In some cases, the fossils would be compared to dried specimens from herbarium collections.

In doing so, the researchers were able to identify the make-up of the plants before and after natural disturbances such as fires and before and after modern-day harvest. The medley of plants from the past was then compared to present-day plants surveyed growing on the surface of nearby peatlands.

Seeds, about 6000 to 4000 years old, of fen plant species. Left: Najas flexilis, an aquatic species; top right: Scirpus validus or Scirpus acutus; bottom right: Menyanthes trifoliata, a typical species found in fens (Vicky Bérubé)

For this specific peatland near the St. Lawrence River, researchers were able to determine that two major fires occurred over the 8,000 year-history. “We can see fires in the peat profiles because they leave a charcoal layer, usually small wood pieces that were burned. Charcoal pieces are quite easy to identify. Under binocular they are shiny and stained,” Bérubé explains.

The study found after the fires the variety of plants in the peatland stayed the same “from centuries to millenia, meaning that a vegetation community can [establish] and last for a long period of time.” The peat cores also showed that from 1946 to the 1990s, after 50 years of peat extraction and no restoration, the peatland lost 2,500 to 3,200 years’ worth of peat accumulation. This historical information is valuable for today’s restoration efforts; we now know that peatlands can recover quickly from disturbance and persist when there aren’t further disturbances.

Growing fens for the future

The study is one of the first profiles of a minerotrophic peatland, or fen, in south-eastern Canada. Perhaps when you think of peatlands you think of peat moss and then you think of bogs. Bogs are one type of peatland, the ombrotrophic or rain-fed type. Bogs (i.e., ombrotrophic peatland) get soggy from precipitation. In contrast, fens or minerotrophic peatlands receive mineral-rich water flowing in from rocky streams and springs. Minerotrophic peatlands are “richer in mineral concentration because their hydrology is tightly linked to the regional watershed and, therefore, they are richer in biodiversity,” Bérubé explained. “This particular type of peatland is also more difficult to study and restore. But there is an increasing interest to restore this type of peatland because of their rarity in south-eastern Canada.”

By coupling paleoecological techniques, including radiocarbon dating, with traditional plant surveys the researchers identified two plant communities indicative of a healthy peatland: brown mosses and tall sedges were important for accumulation of peat post-harvest and stability of the peatland. This type of information can be used to guide selection of plant species for restoration planning, the authors say.

“Rich minerotrophic peatlands are very complex ecosystems because of their biodiversity and water chemistry…going back in time using different methods helps to a better understand the dynamics of an ecosystem,” adds Bérubé.

The study focused on the Bic-Saint-Fabien peatland in the wetlands of the St. Lawrence lowlands—over the last two decades almost one-fifth of the wetlands in this region have been disturbed by various activities including peat harvesting, drainage for housing development, and agriculture.

With new knowledge on peatland ecology being gathered using complementary research methods and landowners and amateur botanists getting involved with conservation, Bérubé is optimistic about restoration of Canada’s peatlands. “There are many possibilities for remediation, rehabilitation or restoration. This [study] can be useful to set up a framework for action.”

The article entitled “Fen restoration: defining a reference ecosystem using paleoecological stratigraphy and present-day inventories” is available for free on the Canadian Science Publishing website.