Earth’s magnetic field is among the key reasons our planet is capable of supporting life, but the magnetic history of our two nearest celestial neighbours—Mars and the Moon—shows that the comfort of having a protective magnetic force field is far from guaranteed.

In a new review paper, Dr. Jafar Arkani-Hamed, emeritus professor of earth and planetary sciences at McGill University, summarized what he and others have learned about the rise and fall of magnetic fields on Mars and the Moon using satellite measurements from NASA’s Mars Global Surveyor and Lunar Prospector.

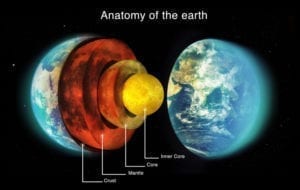

The cores of Earth, Mars, and the Moon all contain an electrically conducting fluid, likely molten iron. If this liquid metal is stirred up in just the right way—for example, through thermal convection—it can develop what’s known as a core dynamo, the source of a magnetic field.

Churning liquid metal in the Earth’s core causes our planet to have a magnetic field.

The dynamo present at any given time leaves a magnetic signature in new rock forming in the crust, such as in cooling lava from a volcano, for example. Even millions of years later, this signature is still present and can be detected by satellites. By comparing magnetic anomalies in parts of the Martian and Lunar crust formed in different eras, it’s possible to reconstruct their magnetic history.

“There are parts of the Martian surface which are highly cratered, hence very ancient,” said Arkani-Hamed. “If a dynamo was present then, it would have magnetized the crust and these craters would produce a magnetic field. But the most ancient craters on Mars don’t show any magnetic anomalies.”

Arkani-Hamed suggested that a large impact around the time Mars formed created the Martian lowland and caused uneven heating in the core, thereby crippling the thermal convection that would have otherwise produced a dynamo.

However, satellite measurements show that about 100 million years after the planet’s formation the thermally driven Martian dynamo eventually did get going, but it didn’t last long.

“Mars is smaller than the Earth, so it cooled faster,” he said. “After about 400 to 500 million years, the core gets colder and doesn’t generate as much convection. At that point, the dynamo fades away.”

Arkani-Hamed’s computer models predicted a different story for the Moon; although it had the conditions to produce a dynamo at formation, the Moon’s small size should have led to this dynamo dissipating after 100 to 200 million years. But that’s not quite what happened.

“The very ancient parts are all magnetic, as expected,” said Arkani-Hamed. “However, the crust of the moon formed at later times is also magnetized.”

This is likely because of the Earth. Arkani-Hamed believes that the interaction between the gravity of the Earth and the Moon, known as tidal forces, stirred up the Moon’s core enough to keep the dynamo going about 600 million years longer than it otherwise would have.

Today, after about 4.5 billion years, the core dynamos on the Moon and Mars are both long dead. But ours is still alive, and because of it, so are we. The magnetic field created by Earth’s dynamo is instrumental in shielding us from the solar wind, a stream of charged particles from the sun that could easily kill all living organisms.

“If Earth did not have a magnetic field, we could not have any life,” says Arkani-Hamed. “That is why it is important to understand what has happened in other parts of the solar system.”

Our existence is more precarious than we might think.

Read the full study: The history of the core dynamos of Mars and the Moon inferred from their crustal magnetization: a brief review in the Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences.