Elegant and strong, teak is revered by homeowners and interior designers. A new paper in the Canadian Journal of Forestry Research tracks 17 years of forest loss and degradation in the global “Home of Teak,” the Bago Mountain Range in Myanmar (Burma).

Though Myanmar’s forest management system provisions for sustainable harvesting, recent practices have ignored these protocols, cutting down too many trees too quickly.

The Bago Mountain Range is in crisis.

To rescue it, forest managers and decision-makers need detailed maps that span hundreds of thousands of hectares.

It’s relatively easy to see forest loss in satellite images, but picking out changes in forest quality is much more difficult. Studies on the subtle effects of forest degradation are uncommon compared to studies on deforestation.

Bago region forests are a mix of valuable hardwoods, like teak and bamboo, which is ignored by loggers. Too much bamboo indicates a degraded, overharvested forest that can’t fully function as an ecosystem.

How do you suss out the bamboo from the teak from 700 km up? Elbow grease.

A picture is worth a thousand words. Two high-resolution satellite images, supplemented by sophisticated software, field data, and interviews with locals are worth an entire scientific paper.

To estimate forest degradation and deforestation, the authors trained software to recognize different types of forest cover. This meant first travelling to 181 locations in the region over two months, recording exact GPS co-ordinates, and classifying each as a healthy forest, degraded forest, or something else.

They fed these data into their software, and had it look for patterns between what the researcher’s saw in the field and the colour or texture of high-resolution satellite images at the same GPS co-ordinates.

This trained the software to identify forest cover in the satellite images with the accuracy of human eyes on the ground.

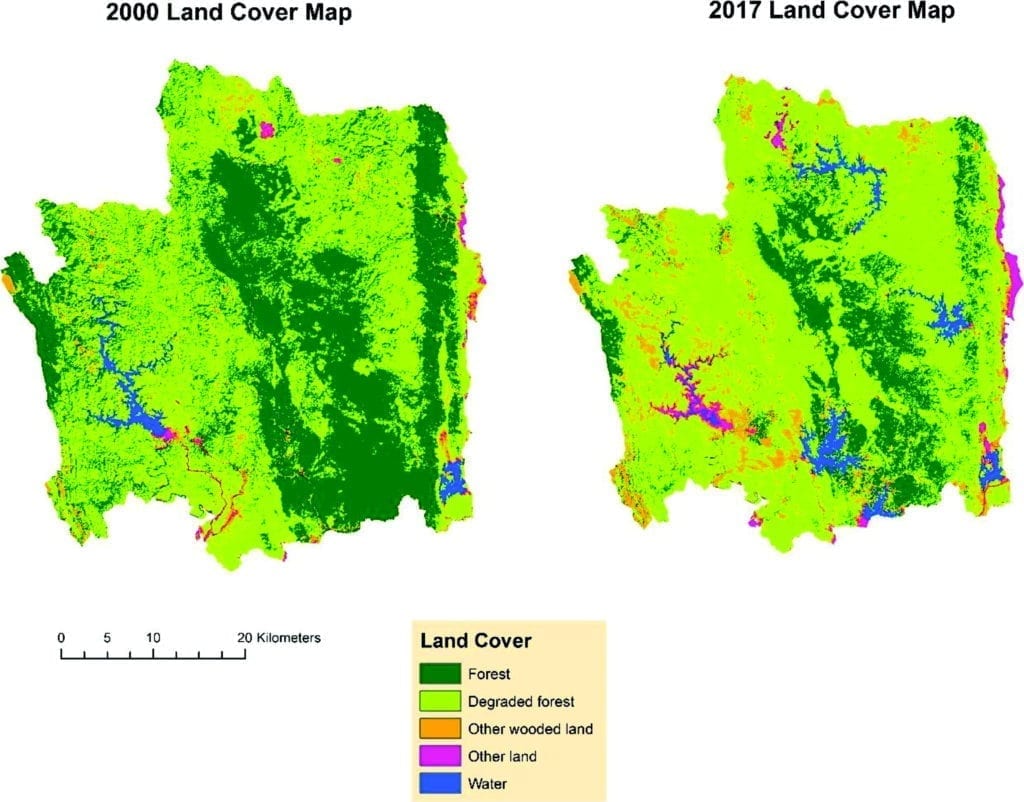

The team then turned their attention to two United States Geological Survey (USGS) satellites images of the Bago region captured in December 2000 and January 2017.

Healthy forest area decreased from 71,240 hectares to 40,891 hectares—a loss of an area about half the size of Chicago. Bamboo-dominated degraded forest area increased by 8,216 hectares over the same period.

There was a substantial change from hardwood- to bamboo-dominated forest cover. In 2000, there were 1.25 hectares of degraded forest for every hectare of healthy forest. By 2017, the ratio was nearly twice that–every hectare of healthy forest was matched by 2.37 hectares of degraded forest.

What happened? The Bago region boomed in the 2000s with the construction of four dams and a highway between Yangon and Mandalay, Myanmar’s two largest cities. It’s much easier to access (and poach) remote trees.

Deforestation and forest degradation are unfortunate consequences of human activity and development. The good news is that degraded forests aren’t a total loss—they can be rescued with decisive action.

In 2016, the government instituted a major reforestation and rehabilitation program, including a 10-year logging ban in the Bago region.

While the ban will stop the bleeding, nursing degraded forests back to health requires more work, including replacing dense bamboo thickets with teak plantations.

Many effects of climate change and human encroachment are slow and hard to see. A simple side-by-side comparison of two images of Myanmar taken 17 years apart brings them into high-resolution contrast.

Read the paper: Quantifying forest loss and forest degradation in Myanmar’s “home of teak” in the Canadian Journal of Forest Research.