Driving north on the Nisga’a Highway in British Columbia, dense forest lines the road. The first sign of volcanic activity looks, to the uninformed eye, like any other valley-bottom lake, until the highway suddenly emerges from the trees onto an expanse of hardened lava.

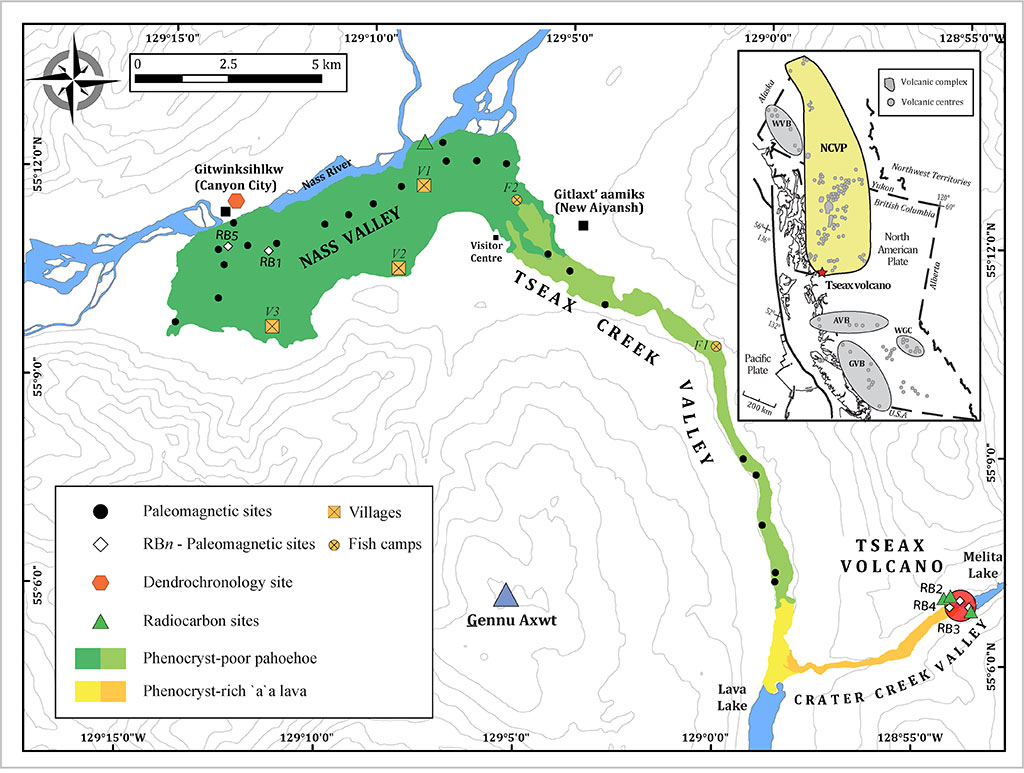

When Tseax volcano erupted, lava spilled down the steep incline of Crater Creek into Tseax Creek, where it formed a dam, flooding the valley behind it and creating Lava Lake. The 40 km2 lava field that remains is a moonscape of hummocky ground, blanketed in tan and green lichens, stretching into the floodplain of the Nass River.

For the Nisg̱a’a Nation, the volcanic eruption was devasting. Lava destroyed three villages on the banks of the Nass River, Laxksiluux, Laxksiwihlgest, and Ts’oohlts’ap, and 2,000 people died, possibly from noxious gases. Despite causing Canada’s most deadly eruption, questions remained about Tseax volcano.

In a study published in the Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences, Dr. Glyn Williams-Jones and co-authors combined radiocarbon and paleomagnetic data with Nisg̱a’a adaawak (oral histories) to determine that Tseax volcano erupted once, between 1675 and 1778.

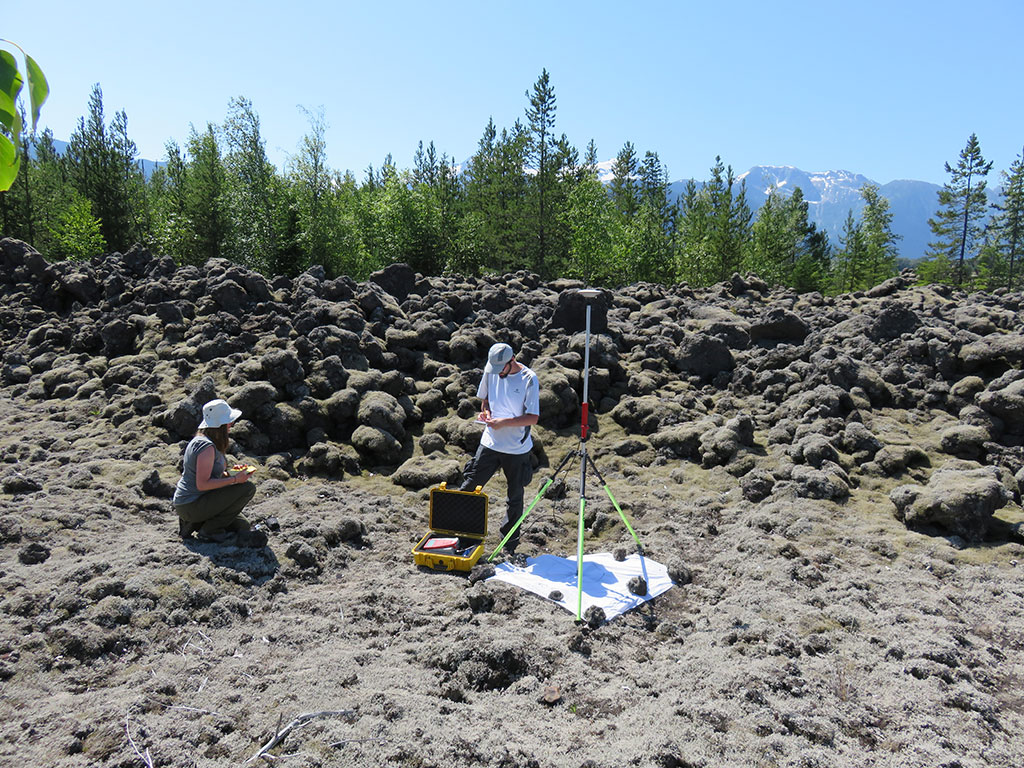

Rose Gallo and Yannick Le Moigne take GPS measurements to map volcanic features | Glyn Williams-Jones

Nisg̱a’a people continue to live in close proximity to the volcano and co-manage Anhluut’ukwsim Lax̱mihl Angwinga’asanskwhl Nisg̱a’a (Nisg̱a’a Memorial Lava Bed Provincial Park). Fortunately, Tseax is what volcanologists call a monogenetic system; it is unlikely to erupt again.

To arrive at that conclusion, the researchers analyzed samples from Tseax’s summit and along the lava field. Magnetic minerals in lava align with the position of the Earth’s magnetic field at the time the lava cools. The Tseax samples all had the same magnetic orientation, indicating the features were formed by a single eruption. Modeling the geomagnetic data with radiocarbon dates from buried trees and information from Nisg̱a’a adaawak, the authors determined that the eruption occurred between 1675 and 1778.

The researchers mapped the lava, which flowed from Tseax volcano (red circle), down Crater Creek valley (orange), into the Tseax Creek valley, where it dammed the creek (yellow) to form Lava Lake (blue at bottom). The lava continued along Tseax Creek valley (light green) to the Nass Valley (dark green).

While this study helped situate the eruption in time, the observational evidence preserved in Nisg̱a’a adaawak describes events in the days or weeks of the eruption itself. In some stories, salmon were swimming upstream before lava flowed down the Tseax Creek valley and pushed the Nass River northward across the valley—placing the eruption between June and September, when pink salmon spawn in Tseax Creek.

These ways of knowing are complementary, but integration can be complicated. Western science has typically operated within a colonial paradigm, extracting knowledge from Indigenous communities.

When Dr. Williams-Jones approached the Wilp Wilx̱o’oskwhl Nisg̱a’a Institute (Nisg̱a’a House of Wisdom) with his research proposal, the Board of Directors were apprehensive. “Understandably, [they] had a concern that I would come in with a Western science approach and say your stories are wrong.” It was important for the researchers to invest the time to understand how the Nisg̱a’a wanted their knowledge to be integrated into the research. “We’ve been able to move forward our understanding of what happened in a culturally sensitive and collaborative way, and I think that is the way we need to be doing science,” Dr. Williams-Jones reflected.

Now, Dr. Williams-Jones hopes the work can eventually be incorporated at Hli G̱oothl Wilp-Adoḵshl Nisga’a Museum, highlighting the region’s unique geology. Referring to the ubiquitous “lava snowballs” that formed when lava rolled onto itself as it hardened, he said, “we saw features at Tseax that have only been rarely viewed at other volcanoes in the world.”

Read the paper: The age of the Tseax volcanic eruption, British Columbia, Canada in the Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences.

Kelly Russell stands next to a 5-m-wide “lava snowball” formed when flowing lava rolls up on itself, like snow sticking to a rolling snowball | Glyn Williams-Jones

Banner image: Tseax lava bed | iStock

Updated: June 23, 2020.