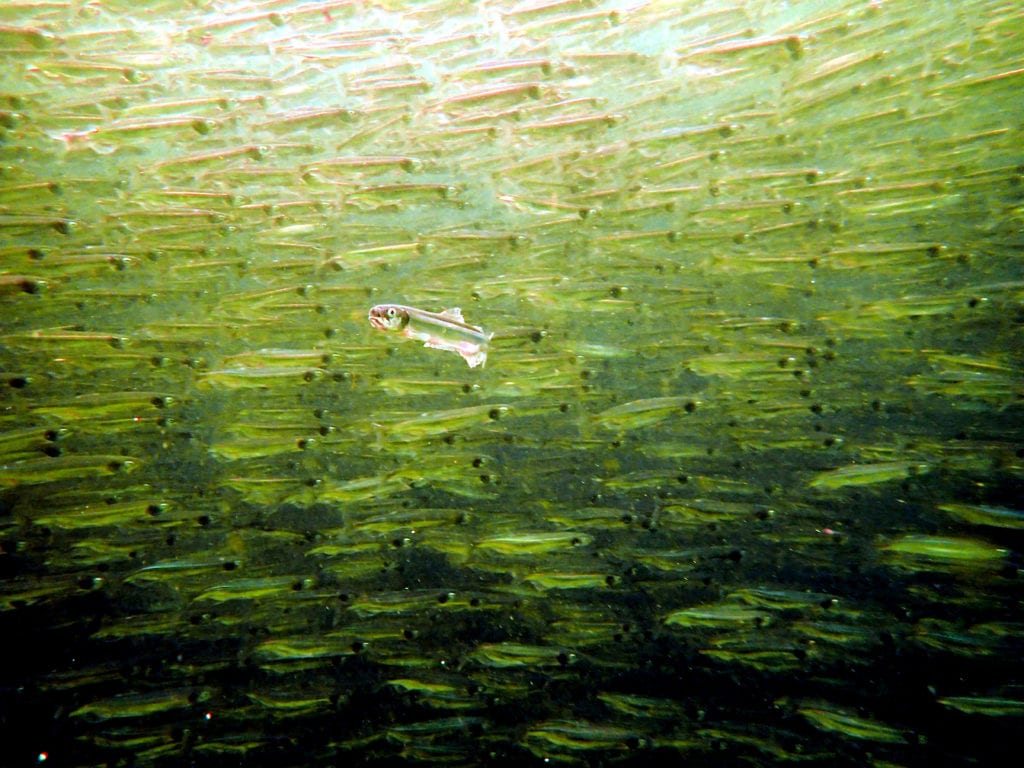

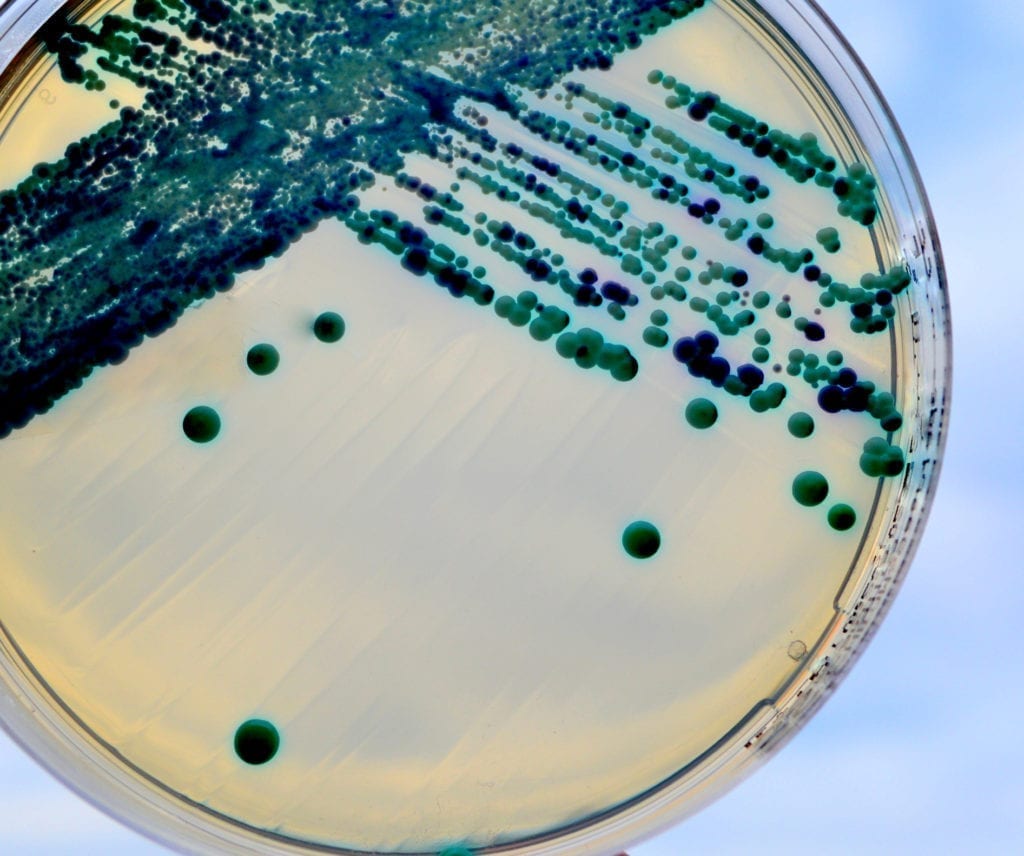

I recently wrote about a study on attaching LED lights to fishing nets. The researchers affixed the lights to the nets used by shrimp fishers to test if illuminated nets caught less bycatch (species not targeted by the shrimp fishery) compared to unlit nets. I was contacted shortly after the issue of the magazine was published by a retired fisheries scientist. This scientist kindly mailed me an offprint of a study he had authored that also investigated effects of light on fishes. Their study was published in 1969. I held the offprint carefully in my hands as if it was an ancient scroll I found in a weathered, glass bottle that had washed up along the shores of the Atlantic.

It’s okay if you rolled your eyes at that statement.

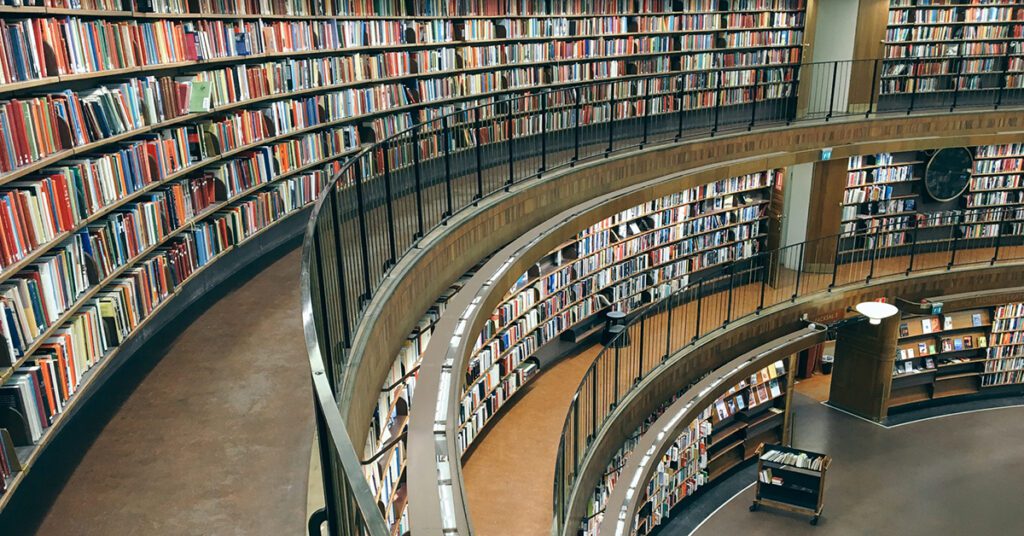

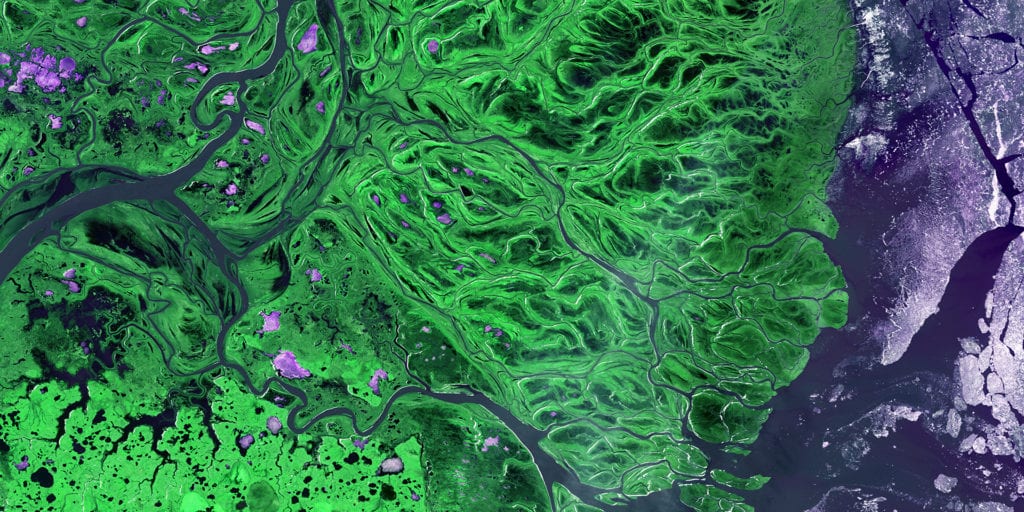

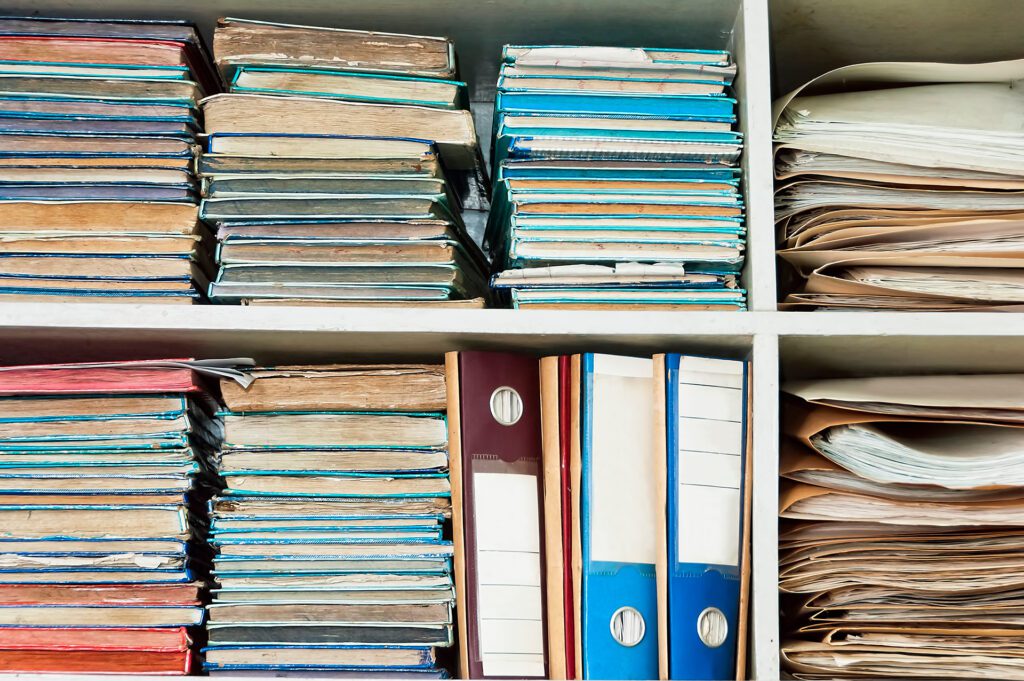

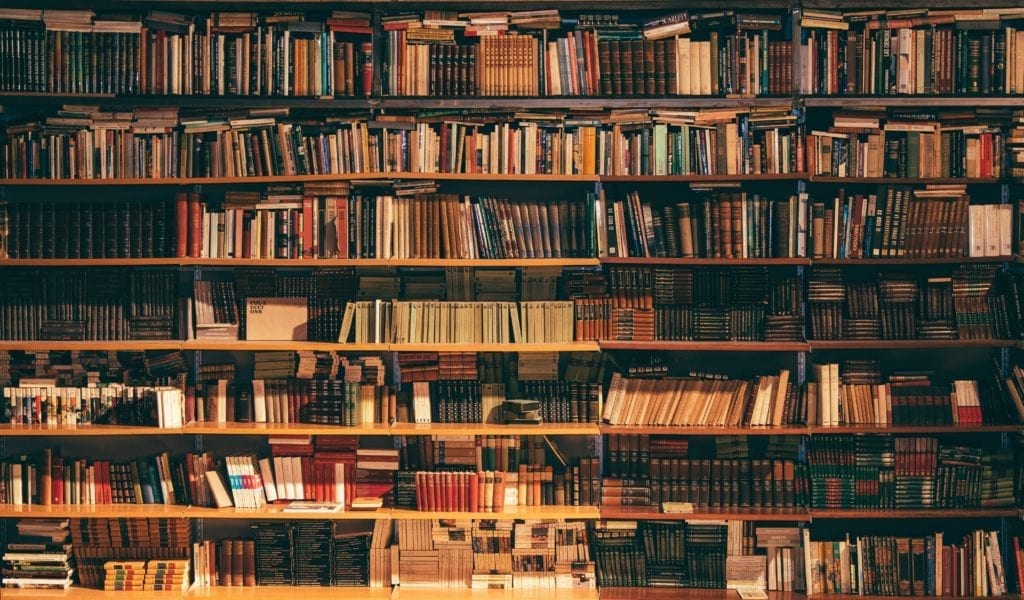

By the time I stepped onto a university campus, accessing journal articles digitally was the norm. During my MSc and PhD, highly sporadic trips to the library to find the hardcopy of an article would result in adventure. I ended up in the Rare Books & Special Collections at the University of British Columbia for the first time in 2012. I was searching for a paper from 1963 entitled “Energy required for swimming by young sockeye salmon with a comparison of the drag force on a dead fish.” How absurd! Before entering the room I had to remove my backpack, then my coat, then any pens from my pockets, then the gum I was chewing. The librarian retrieved the journal and sought permission to photocopy the article I had requested (splaying the book open on the photocopier could compromise the integrity of the seams). While waiting, I pondered the dystopian chaos of Ray Bradbury’s Farenheit 451. I looked around the room. There was a student handling a book wearing white, cloth gloves. The librarian returned with the photocopied article. The sheets of paper were still warm. The whole experience was actually quite thrilling. I remember it vividly.

Why haven’t I gone back to such a place?

Access to older articles is increasing. I, a fish biologist, now seldom go to the library. I seldom relive that sense of, dare I say, excitement when you locate the correct journal volume and flip to the page of the article you are hunting. I seldom feel the same appreciation or reverie of yesteryear’s research while staring at a PDF of an older article.

What am I missing by not physically entering a library?

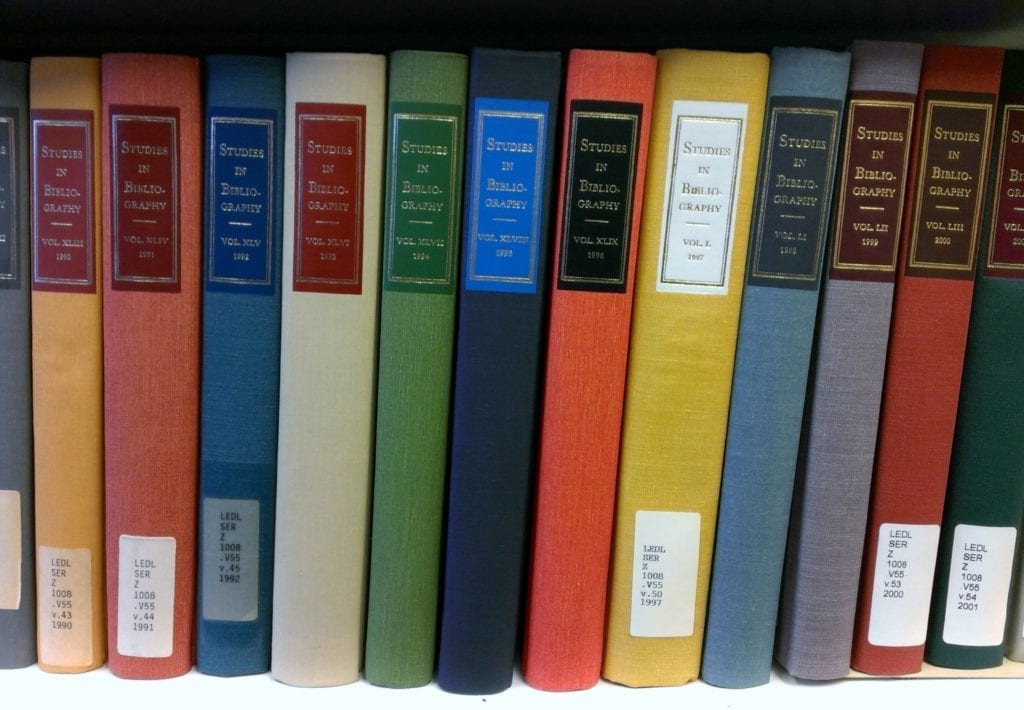

I began postdoctoral research at the University of Windsor in September of last year. Six months later I stepped into the campus’ main library, Leddy Library, for the first time. The library was named after the university’s first president, Dr. John Francis Leddy who was appointed in 1964. This blog series, Library Nexus, will explore how, in a digital era, libraries shape the connections between scientist and science, history and science, and art and science.

Day 1: Prep

In the morning, I searched the library’s online catalogue for specific papers I was keen on finding. One of the papers being an early description of the toadfish, Porichthys notatus, or plainfin midshipman. I have a PDF of this paper, and it’s available online. But what other natural history gems would I happen upon when I read the article in original print? Much to my dismay, it appeared as if none of the fish/fisheries journals I regularly browse were going to be on the shelves of Leddy Library. My colleague, Holly (who completed her undergraduate degree at the university), assured me that there were indeed hardcopies of journals. She offered to give me a brief tour of the library. I accepted and we both ventured from the office.

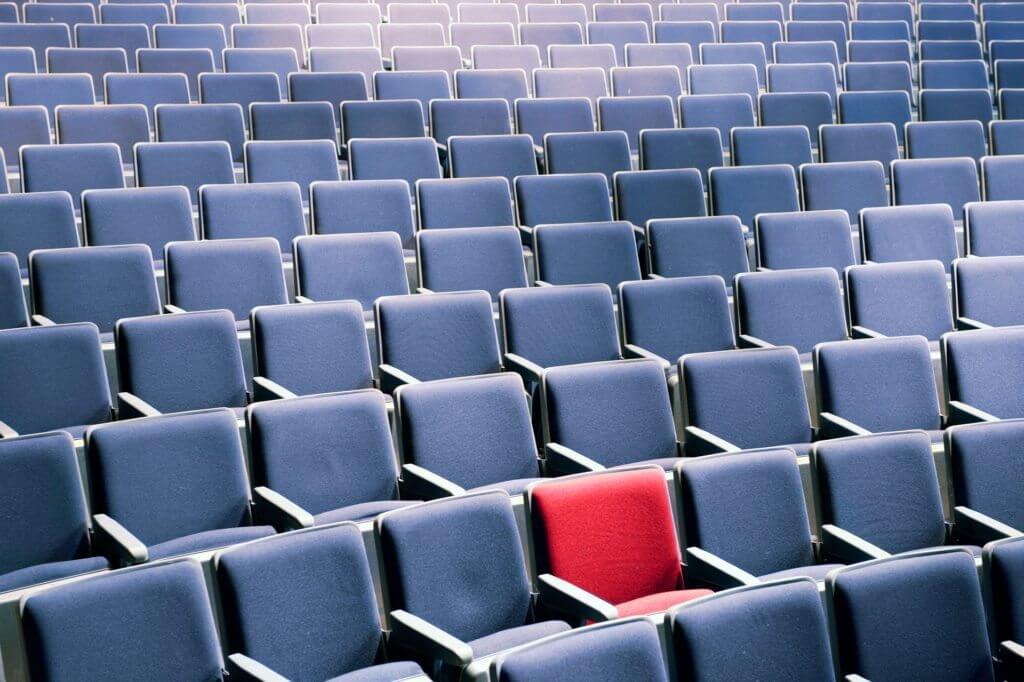

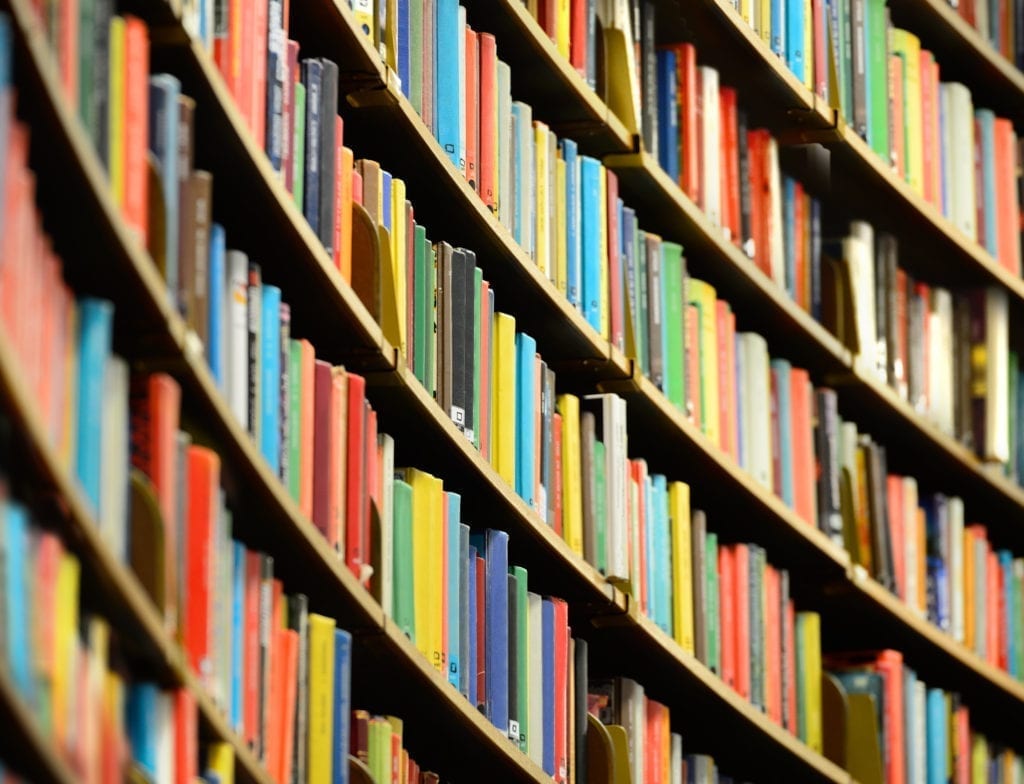

Entry to Leddy required passing through a turnstile. We passed dated walls of coffee-coloured brick. We casually glanced at the stacks of microfilms. There were tables and desks occupied with students and their laptops, but the aisles between the bookshelves were mostly vacant. On the ground level of Leddy, in the “West Wing”, is mobile shelving. Holly was correct; there were bound journals among these electronic racks. I was on a mission for aquatic-themed journals. I wandered among the shelves scanning journal titles: Storm Data, Fertility and Sterility, Journal of Agricultural Economics, Heating, Piping and Air Conditioning, Tetrahedron, Journal of Algorithms. There is no shortage of engineering journals at Leddy Library – ceramics, electrical, civil, chemical, manufacturing, aviation, reliability, metallurgical and automotive engineering are all in existence. My pace quickened. Between “Ranges 10-12” I found what I was looking for. I emitted a sigh of relief when I saw an olive-tinted spine with gold embossing that spelt, Animal Behaviour. First time I’ve been relieved to see a periodical. I did not encounter Journal of Fish Biology or Fish and Fisheries, but there were multiple volumes of The Aquarium. I was instantly intrigued. The eye-catching apple-green spines of Journal of the Linnean Society of Londondated back to the 1800s. Within 15 minutes of arrival my curiosity was ignited. What content was in these timeworn and unfamiliar journals?

Day 2: Peruse

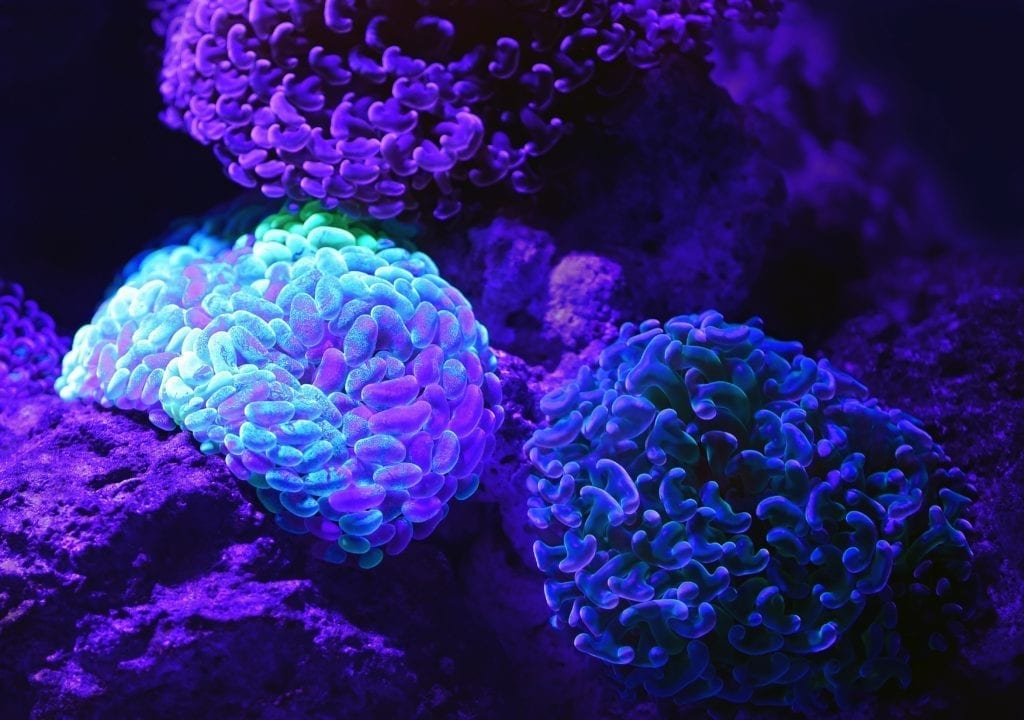

The following day I beelined to the volumes of The Aquarium. The earliest volume available at Leddy Library is from 1950. I opened the navy-bound book and found myself immersed in the world of fish keeping, from “cleaning clogged filter tubes” to “drying daphnia without lumps”. Even 60 years ago it was recognized that “filming fish is tough but it can be done.” The Aquarium, a monthly magazine, was founded, edited and published by William T. Innes, a renowned American aquarist. The first volume of the magazine was released in 1932 but the practice of keeping live, aquatic organisms in a container of water dates back to the Victorian era. I put the volume on the return cart and recalled my days cleaning aquaria in a lab as an undergraduate.

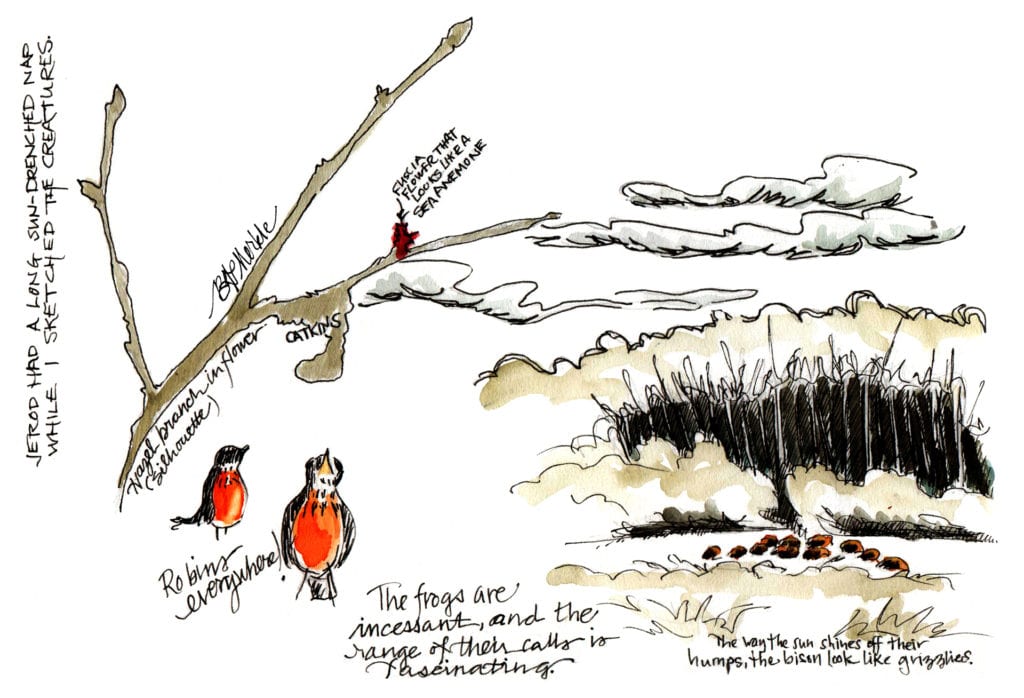

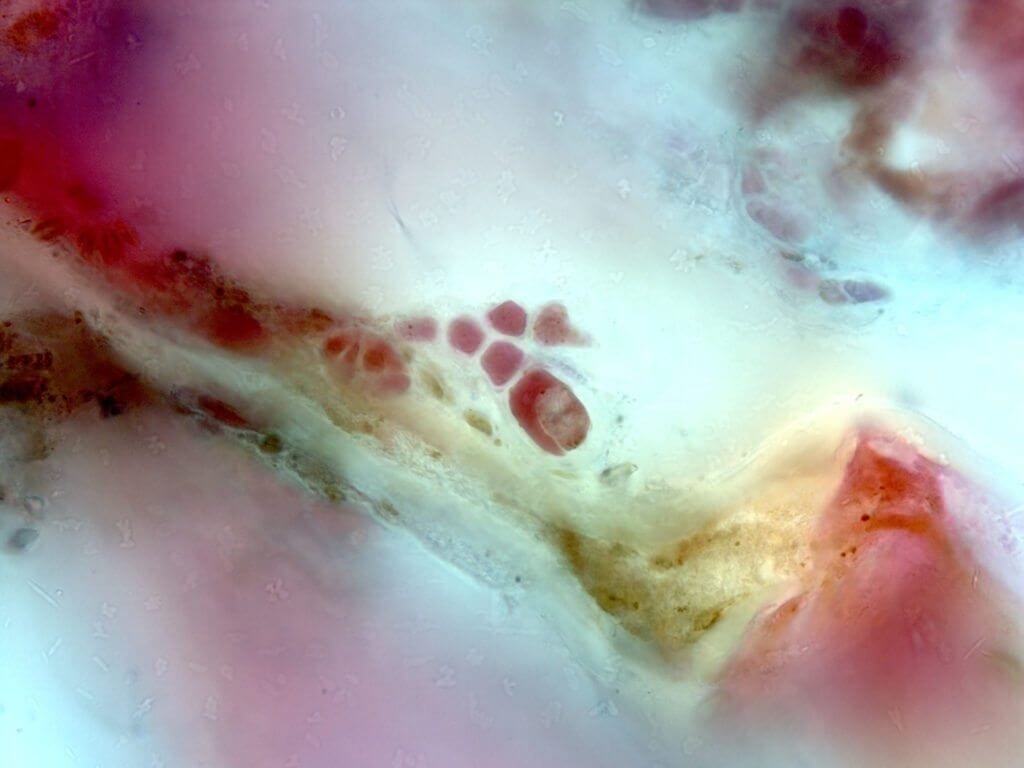

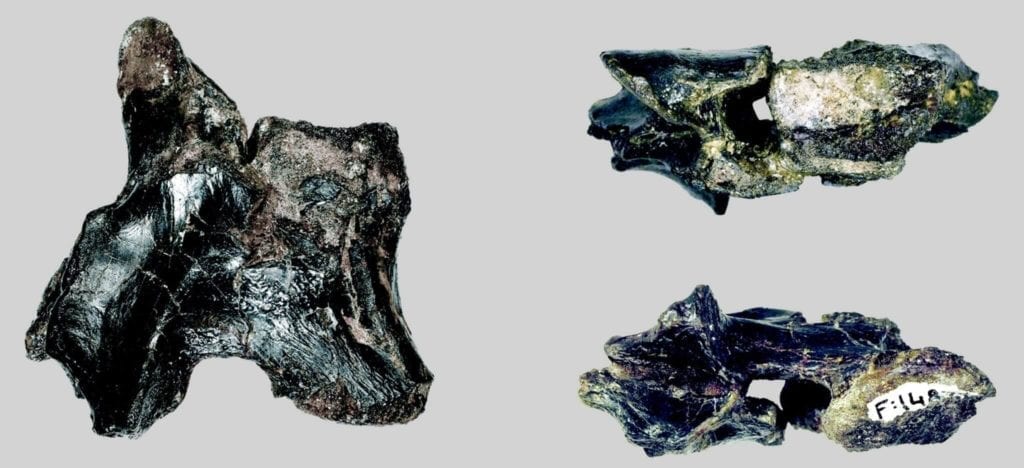

With Taxonomist Appreciation Day fresh in my mind I next grabbed the earliest available volume of Journal of the Linnean Society of London. Published in 1887 and 1888, issues 136 to 140 are collectively a 300 page opus describing approximately 160 species of Crustacea from the Mergui Archipelago. There is a sole author and illustrator for this body of work, J. G. de Man. I wonder how many hours were spent scrutinizing specimens, agonizing over taxonomic classification, illustrating the minutia and typing this tome. The pages were filled with immaculate details of anatomical features like the “five small, blunt, semiglobular tubercles or spines [are] found on the anterior declivity” of the shell of the crab Hyastenus pleione and “arranged in an arcuate line;” As I read that hermit crabs have “hands”, “fingers” and a “palm”, I stared at the appendage holding the pen I was using to scratch down notes. It was the telling of the “musical crest” when I felt inspired. de Man described a ridge on the inner-side of a male’s claw and named it the “musical crest”, proposing that a sound was produced when the claw with the “musical crest” was rubbed against bumps on the crab’s shell, near its eyes. I imagined a crab on a beach, racing into a pool of water for refuge as the tide rushes out. He wipes his brow in relief and a gritty sound echoes along the intertidal.

Day 3: Ponder

I went to a library, so what? It was enthralling exploring an unknown library’s periodicals for the first time. Ideas, and the potential of generating more ideas for my fish-poetry blog abounded. I anticipated this happening. I believe this sense of opportunity translated into an urgency to return to the library, not only because I was acquiring material for this very piece of writing, but because of what I envision as a creativity bubble that formed around me. I opened one book,and immediately wanted to scour for inspiration in the next book. I’m always searching for ways to recharge my creativity and I am a proponent of creativity being inherent to science. This experience was also overwhelming, even though the collections at Leddy Library are small relative to other universities. What exquisite content was I overlooking? I suppose I can search online for what I overlooked. But how does serendipity and happenstance manifest in a digital realm?

On Twitter, #365papers is a goal for academics to read a paper a day. Although it may seem trivial to read one paper a day, it is an ambitious feat. The first hurdle being the decision of which paper among the plethora to read. Once you’ve decided, might I recommend heading to the library to unearth the paper and read it in your own creativity bubble?