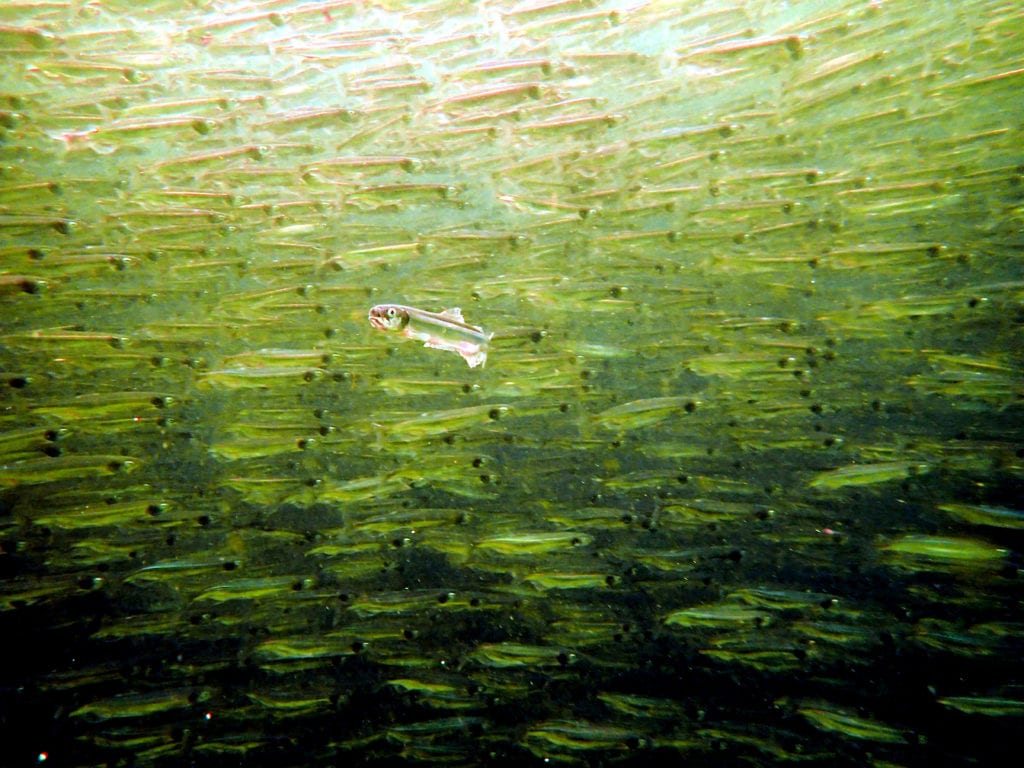

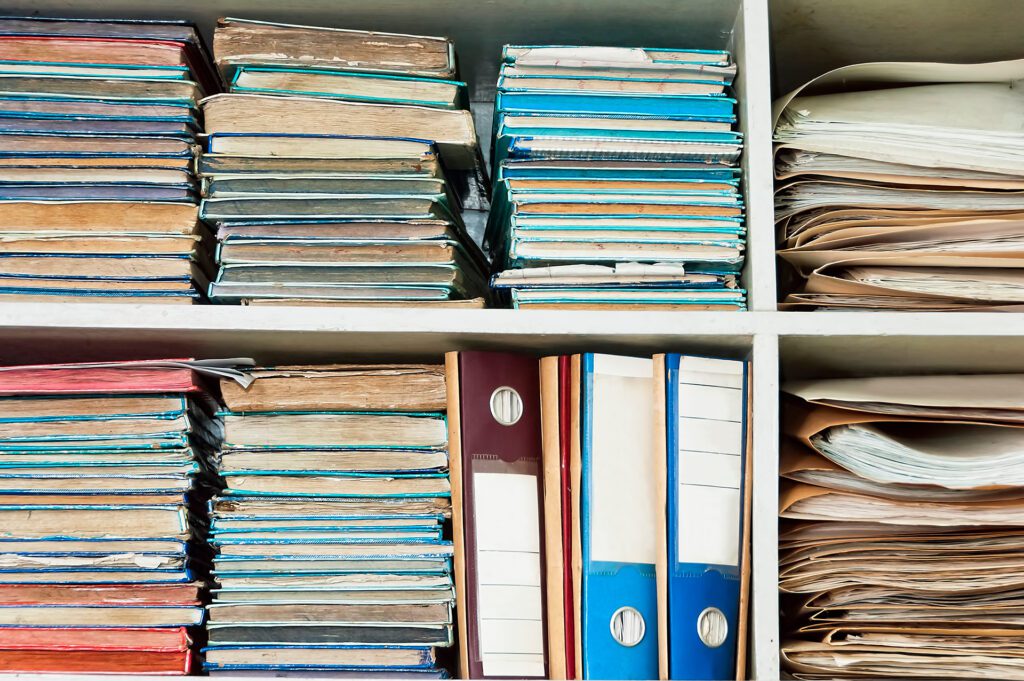

Do you feel overwhelmed by the number of research papers in your field? Do you wonder if you’re missing key ideas that could be critical for your research program? Does it feel like the deluge is only getting worse?

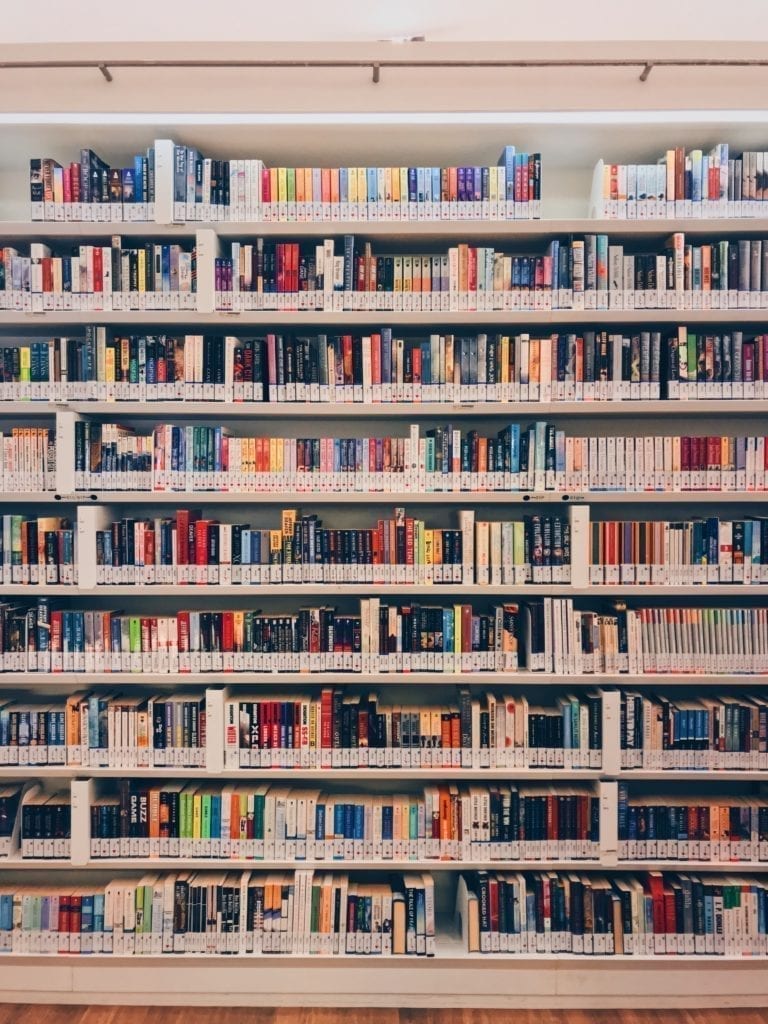

You’re not imagining things. According to research from the University of Ottawa, in 2009 we passed the 50 million mark in terms of the total number of science papers published since 1665, and approximately 2.5 million new scientific papers are published each year.

What’s driving this publication explosion?

At its most basic level, we’ve seen a substantial increase in the total number of academic journals. As of 2014 there were approximately 28,100 active scholarly peer-reviewed journals. Add to this the increasing number of predatory or fake scientific journals, which produce high volumes of poor-quality research, and you have a veritable jungle of journals to wade through.

Another key factor is the sheer number of publishing scientists worldwide, which is increasing at a rate of approximately 4-5% per year. In British Columbia and Alberta alone, we’ve seen the conversion of more than seven colleges to universities in the past decade, and with these changes come new pressures on faculty to publish.

This pressure to “publish or perish”—and the increased competition amongst this growing pool of scientists—has resulted in some researchers becoming what’s termed “salami slicers.” They divide papers into the least publishable unit in order to lengthen their publication list, increase the chances of being cited, and increase the opportunity to publish in journals with a high impact factor. This further contributes to the volume of papers published.

How does this paper deluge affect the scientific endeavour?

In a 2008 study, James Evans, a sociologist at the University of Chicago, suggested that the profusion of papers and associated ease of online access had led to a “narrowing of science and scholarship,” an echo chamber in which many researchers cited the same small pool of more recent studies to support their claims. He surveyed articles with citations from 1945–2005 and showed that, as more articles appeared online, scientists cited fewer of them in total and cited more recent ones with higher frequency, suggesting that older literature was no longer being read and/or cited.

Not everyone agreed with his results, however (see the ‘Letters’ at the bottom of this link). Some argued that, with more publications available online—and the digitization of older material—scientists had increased access to references that may have been more difficult to find in the pre-digital age. Others argued that, even with so many papers available online, digital search algorithms made it possible to efficiently separate the wheat from the chaff for research purposes.

Evans’ argument that fewer old studies are being cited is definitely a concern: one doesn’t want to accidentally reinvent the wheel by neglecting the relevant older literature. But as Jeremy Fox at Dynamic Ecology argues, an entrenched culture of reading and citing older papers can also hamper the advancement of a discipline because it “risks closing the field off to worthwhile input from outsiders.” While those ‘outsiders’ may have some unique ideas, they likely don’t have the same depth of knowledge as disciplinary ‘insiders’. In an era where interdisciplinary research is considered critical to solving many scientific problems, this can be a significant stumbling block.

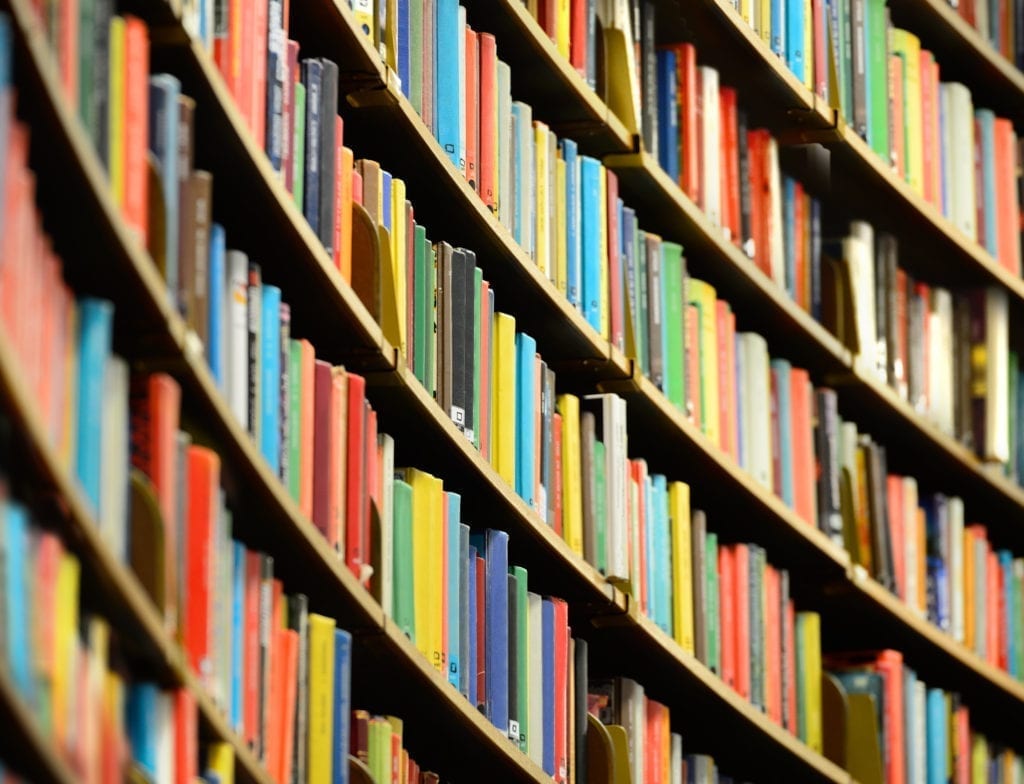

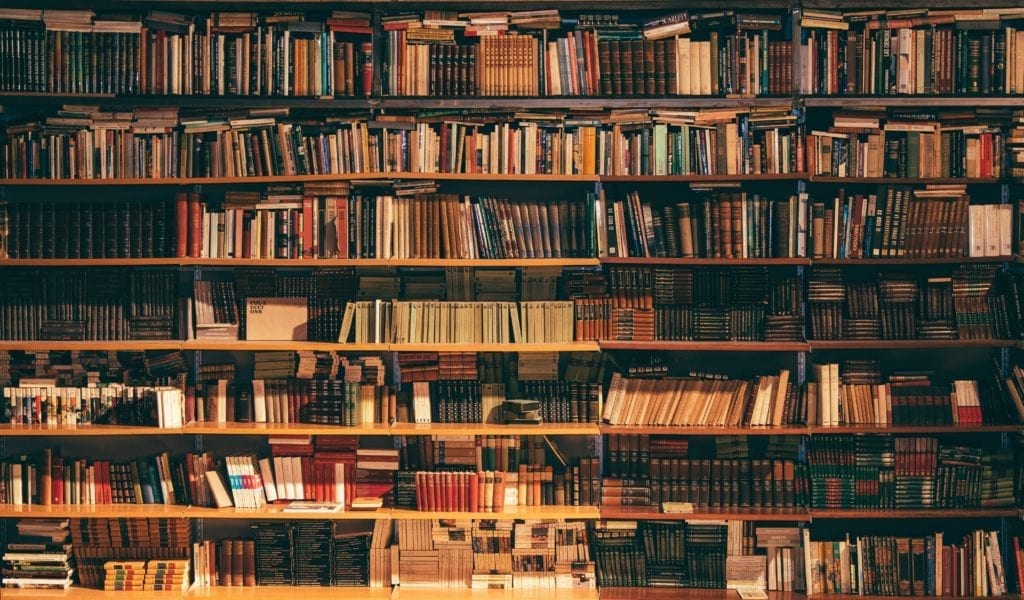

I did my PhD on the cusp of the digital revolution. While I could find many new papers online, most of the older work was still in hardcopy format. I spent a lot of time at the library, photocopying, but I also used that time to browse. I’d look at other papers in the journals I was photocopying, and browse books on the shelves near where I found these journals. I’d often fortuitously stumble across something relevant that I wouldn’t have found otherwise. Browsing allowed me to think laterally, to compare my research and results with work that perhaps overlapped on only one particular aspect. These comparisons sometimes shed light on my project, which might not have happened had I not found a particular article or book.

Thus, while the deluge of scientific papers may be managed with more efficient online searches that allow researchers to drill down into their research field more deeply, there are two possible drawbacks. One is that we’ll neglect the older literature, and the other is that we’ll lose our ability to explore laterally: to unexpectedly brush up against other studies, or even other disciplines, where we find information that’s potentially relevant to our current research.

How can we make the most of the digital deluge without compromising science quality?

There are several approaches that individual scientists can consider to make the most of the digital revolution while maintaining scientific integrity.

When citing an older paper in your work, always go back to the original rather than using a citation of that work from a more recent paper. This will keep from potentially propagating so-called “zombie” ideas: those that originate from a simple misunderstanding of the original paper, but are propagated through the literature because no one goes back to the original paper to verify the original idea.

As noted by Fox, don’t assume that the older literature automatically carries more weight than current literature—read both with the same critical approach.

Make time to read not only older literature, but current literature that’s related to—but not explicitly part of—your research. In an era where we seem to have less and less time for tangential tasks that don’t contribute directly to moving our careers forward, this can seem like a tall order. One way to simplify it is to solicit suggestions of “must read” older papers from more established researchers in your field. The other approach is to set aside an hour each week to browse new abstracts in relevant journals.

Finally, there’s a tool in development for science journalists that may be just as useful for scientists. The goal of Science Surveyor is to develop an algorithm that will take the text of an academic paper and search academic databases for other studies using similar terms. It will then present related articles, and also show how scientific thinking has changed over time by analysing how language is used across all the selected articles. Researchers—particularly those getting into new research fields—could use this type of algorithm as a first step in getting acquainted with the research field and how it’s changed over time.

One thing is for sure—the publication explosion isn’t going away, so the better we can manage it, the more likely we’ll be able to make the most of it.