The economic value of some forest land may rest not in the standing timber, but in the soggy dirt and tangled mass of roots below.

Because of their natural symbiotic association with trees, many varieties of edible mushrooms flourish on forest floors around the world. They not only offer a prized source of food, but also can account for more than half of local incomes, as in some regions of Southwest China.

With the international market for wild fungi mushrooming, researchers at Guizhou University’s Institute for Forest Resources and Environment and their colleagues conducted a comprehensive study of Suillus bovinus (a common but not fully exploited fungus also known as the Jersey cow or bovine bolete mushroom) to better inform its harvesting and production.

S. bovinus thrives on the soil nutrients found around pine trees. It reciprocates as a mycorrhizal fungus by extending fine filaments into the tree roots, thereby helping them draw water from tiny pockets in the soil.

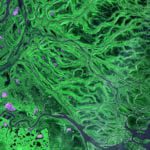

The investigation, published in the Canadian Journal of Forest Research, reports on a three-year field survey of a Chinese Red Pine (Pinus massoniana) plantation in Longli County as well as previous field research and laboratory studies.

The research team was driven in part by a desire to refine the morphology of the S. bovinus mushroom and to inventory the distinguishing features of its form and structure. This is needed because edible and poisonous fungi can be easily confused. The authors noted, “poisoning incidents frequently occur all around the world” especially in the Guizhou region, adding that this is “the main cause of mortality in food poisoning incidents in China.”

Even when different edible mushrooms are muddled, the consequences can be significant for local livelihoods and the development of an export industry.

Clarified identification techniques are not enough to ensure sustainable production when harvesting a wild crop. This research may, therefore, be of greatest interest for the light it sheds on the growth of the sporocarp, the fruiting mushroom body. Generally, increases in temperature and precipitation align with increases in sporocarp growth. But questions remain about what constitutes limiting climatic conditions and, intriguingly, how much the rain and heat directly affect the fungi, if at all.

Because the growth in the mushroom fruiting parts correlates with the growth phases of the trees, the fungi may, in fact, be benefiting from excess photosynthate nutrients produced by their hosts during hot, rainy days of early summer more than the warmth and wetness of the soil. Other observations that invite further study include the regular presence of Gomphidius roseus, a rose-coloured fungus normally thought to be a parasites.

This suggests that forces at work on the forest floor may involve triangular interactions and a complex ecosystem that demands careful silviculture as well as harvesting techniques that are sustainable and economical. Though this study provides a framework of fungi knowledge, it advocates further work to ensure we make the best of another symbiotic relationship—the one between humans and mushroom-rich forests.

Read the full study: Phenology and cultivation of Suillus bovinus, an edible mycorrhizal fungus, in a Pinus massoniana plantation in the Canadian Journal of Forest Research.