The days of treading through tough Bornean brush in an attempt to spot elusive orangutans may soon be over—or at least made a lot easier. In a pilot project, a team of astrophysicists, computer scientists, engineers, and ecologists have developed a method of observing orangutans and proboscis monkeys using thermal-equipped drones. They hope to advance their technology to be able to detect all sorts of animals using thermal drones.

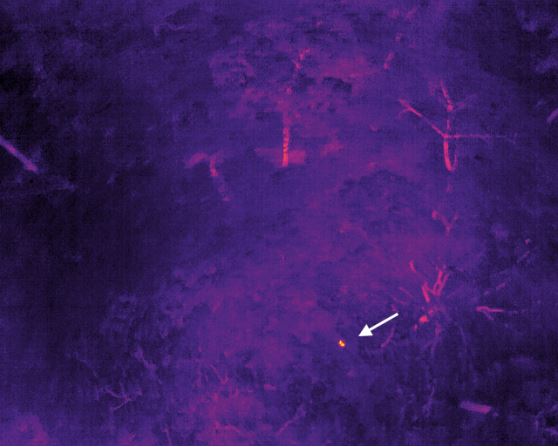

Orangutan detection using ground level thermal camera.

“Instead of wandering around the jungle not sure where anything is, you fly the drone around and you’ll get an idea of where specifically orangutans are,” said Claire Burke, lead author of the study and astrophysict at John Moores University in Liverpool.

Studying orangutans by foot can be slow and laborious. Only small areas can be covered, and dense vegetation and nightfall can spoil the likelihood of observing animals. Drones can be deployed over large areas, and thermal cameras allow for orangutans to be tracked through the lush canopy and during the evening.

For the study, published in the Journal of Unmanned Vehicle Systems, researchers first followed orangutans on the ground until they nested. Then a drone was flown over nesting sites to test if the thermal cameras could reliably spot the orangutans. Second, the researchers flew a drone around in a grid-like pattern to detect orangutans, and then sitings were confirmed on the ground. In total, the thermal drones accurately detected 41 orangutans as well as a troop of proboscis monkeys.

Orangutan detection using thermal-equipped drone.

The project was successful overall, but using thermal drones still comes with its own set of challenges. “If your surrounding temperature is too warm—at a similar temperature to what you’re looking for—then you actually can’t see the orangutan,” said Burke. “In the middle of the day, especially in warm tropical areas like Borneo, when the sun has been beating down on the jungle for a while, the leaves get quite warm and it’s impossible to actually see any animals. So the limitations are we have to fly first thing in the morning or last thing at night.”

Currently the thermal drones can be used in conjunction with ground surveys, but the research team plans to take the drone technology much further: “Our next step is to build a machine-learning system that can actually tell the difference between what to our eyes looks like a bunch of differently shaped blobs and be able to say with some amount of confidence that that is an orangutan.”

Once a machine-learning system is developed, the research can extend far beyond detecting orangutans in Borneo. “We’ve found that different species of animals have unique thermal fingerprints—their bodies are warm and cool in different places,” said Burke. By training a machine learning system to distinguish between these “thermal fingerprints”, different species can be detected automatically.

“We’re developing the tech to be as broadly useful as possible,” said Burke. “We want to be able to detect and identify as many different species of animals as we can all over the world.”

Read the full study: Successful observation of orangutans in the wild with thermal-equipped drones in the Journal of Unmanned Vehicle Systems.