If you’re a regular consumer of science stories, you’ve doubtless noticed some seismic shaking across the (cliché alert!) media landscape. Science journalism, like many forms of communication, has transitioned from an industry regulated by a handful of gatekeepers—National Geographic, Scientific American, a few daily newspapers—to a diffuse business. To cite one telling statistic, the number of U.S. newspapers with weekly science sections plummeted from 95 in 1989 to 19 by 2012.

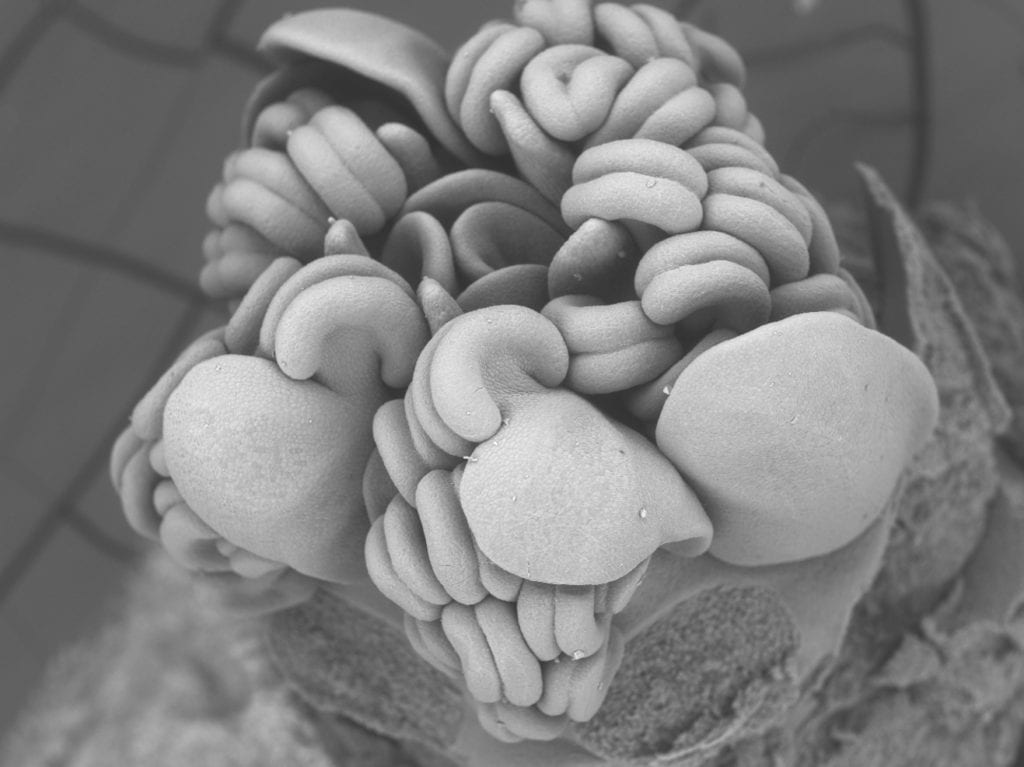

The decline of science in daily newspapers represents a tragic loss, one that’s cost many wonderful writers their jobs. And don’t even get me started on the fact that National Geographic is now owned by a climate denier. Still, a note of optimism: We are living in the midst of a Cambrian explosion of science media.

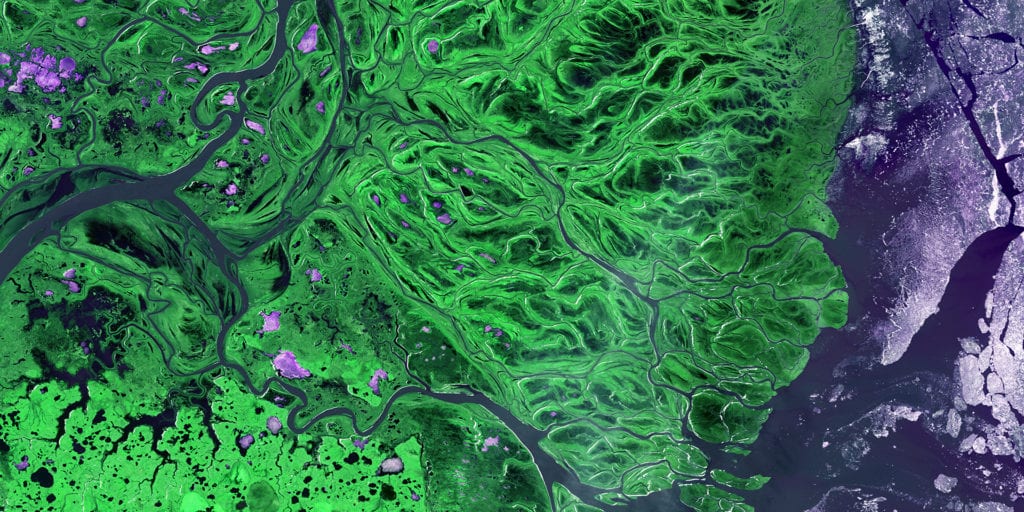

In recent years, countless publications have arisen or been revitalized, radiating outward to fill various niches: Nautilus, Matter, InsideClimate News, Pacific Standard, and many more. As advertising dollars dry up, non-profit outlets—OnEarth, Hakai Magazine, High Country News—have flourished. Innovative funding mechanisms have sprung up, too, including Beacon, Big Roundtable, and the just-launched Word Rates. These new publications have facilitated a spectacular resurgence in a form that many assumed the internet would kill: longform. No longer are old-media bastions like The New Yorker and The Atlantic the only purveyors of the 8000-word behemoth; these days, even listicle-peddlers like Buzzfeed are heavily invested in in-depth reporting and narrative journalism.

Combine a wave of new publications with a relaxation of space constraints, and you have the formula for a storytelling revolution. Sure, science writing will always have room for the “Hey, look at this neat new study” story—in fact, that’s 95 percent of what currently gets published. Still, science journalism is increasingly designed not merely to convey information, but to transmit a narrative with a beginning, a middle, and, if the writer is truly fortunate, even an end.

What does this mean for you, the scientist who’s a source to all these eager, narrative-obsessed beavers? Mostly it means we, the journalists, are going to ask you different questions, with different expectations. We want depth, scene, nuance, description, internal conflict. We want to hear about your screw-ups, your darkest moments, your methodological tweaks, your joy. To my mind, the results are rarely the story per se—they’re the culmination of an involved and emotionally complex tale.

So: If you, too, would like to be part of the narrative revolution, or if you want to control your own story, or if you want to make a compelling case for your funders, or if you just want to help out jerks like me, here are three things you might consider keeping in mind next time you’re talking to a journalist.

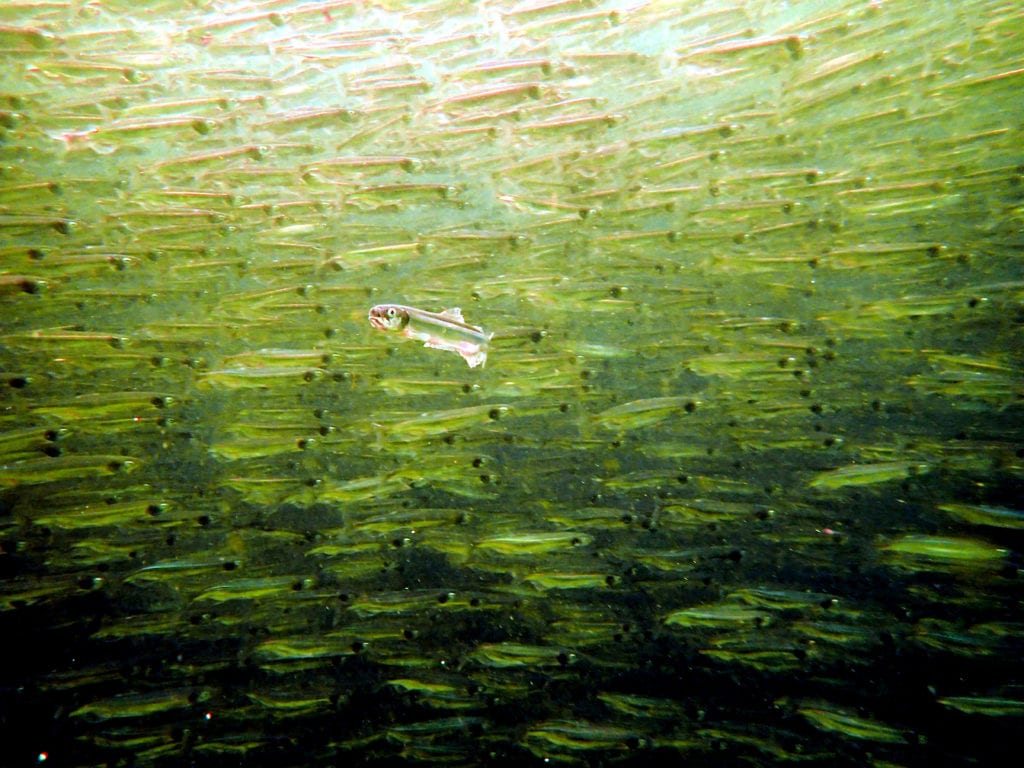

1) What’s your origin story—why do you care about what you study? This works especially well when you work on, say, the humpback chub, or the Pacific lamprey, or some other obscure but quietly charismatic species; though these examples are tailored to fish biologists, the concepts apply to researchers of all intellectual persuasions. Think of yourself as a superhero: Spiderman was bitten by a spider; Batman fell into a bat pile at the bottom of a well (presumably Alfred administered some rabies shots). What could possibly have happened to you to make you care about the canary rockfish?

2) What got you interested in your particular question/project? It’s wonderful that you love the Colorado topminnow—but why did you want to know x about the Colorado topminnow? Why did you start thinking about translocating razorback suckers, or tracing the spread of Asian carp with eDNA, or what have you?

One quick example: Earlier this year I wrote about Johanna Varner, a biologist who intended to do her PhD on the thermal tolerance of pikas (the cutest member of Animalia). But disaster struck when her study sites were torched by a wildfire. At first Johanna was demoralized… until she realized that nature had set up an incredible natural experiment. She eventually published a fascinating paper on pika’s resilience to fire. Your own story might not be so dramatic, but you’re investigating specific questions for a reason.

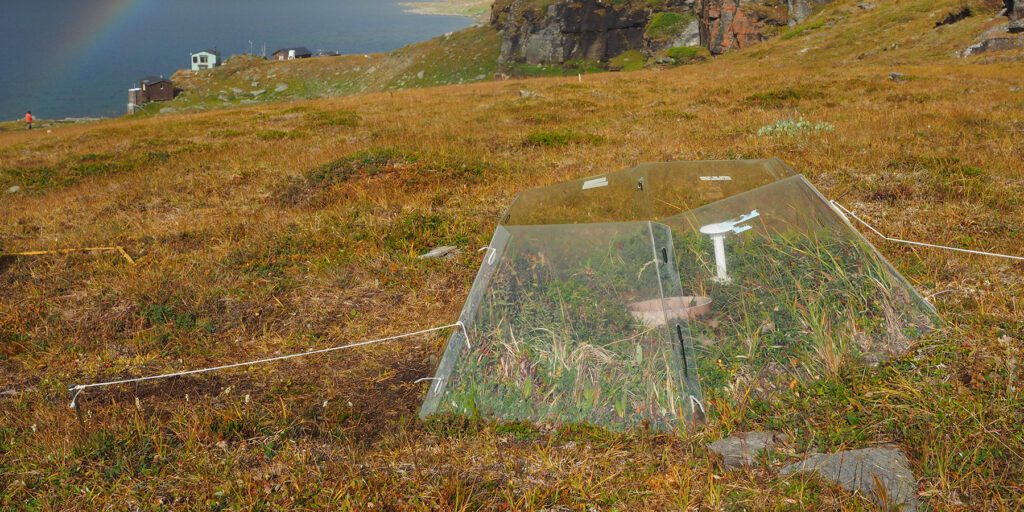

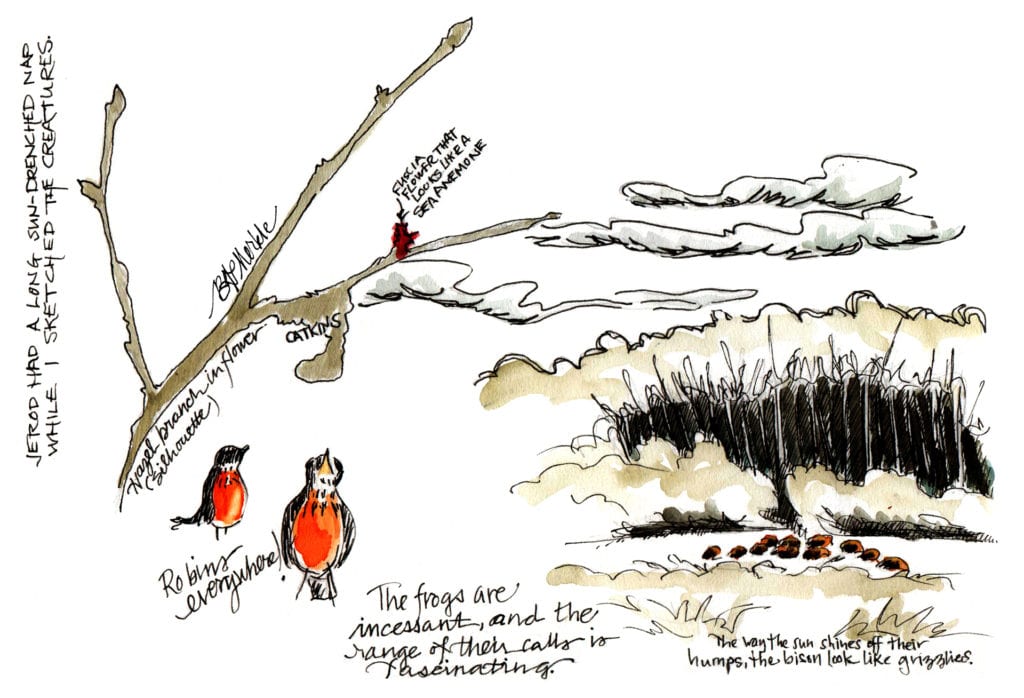

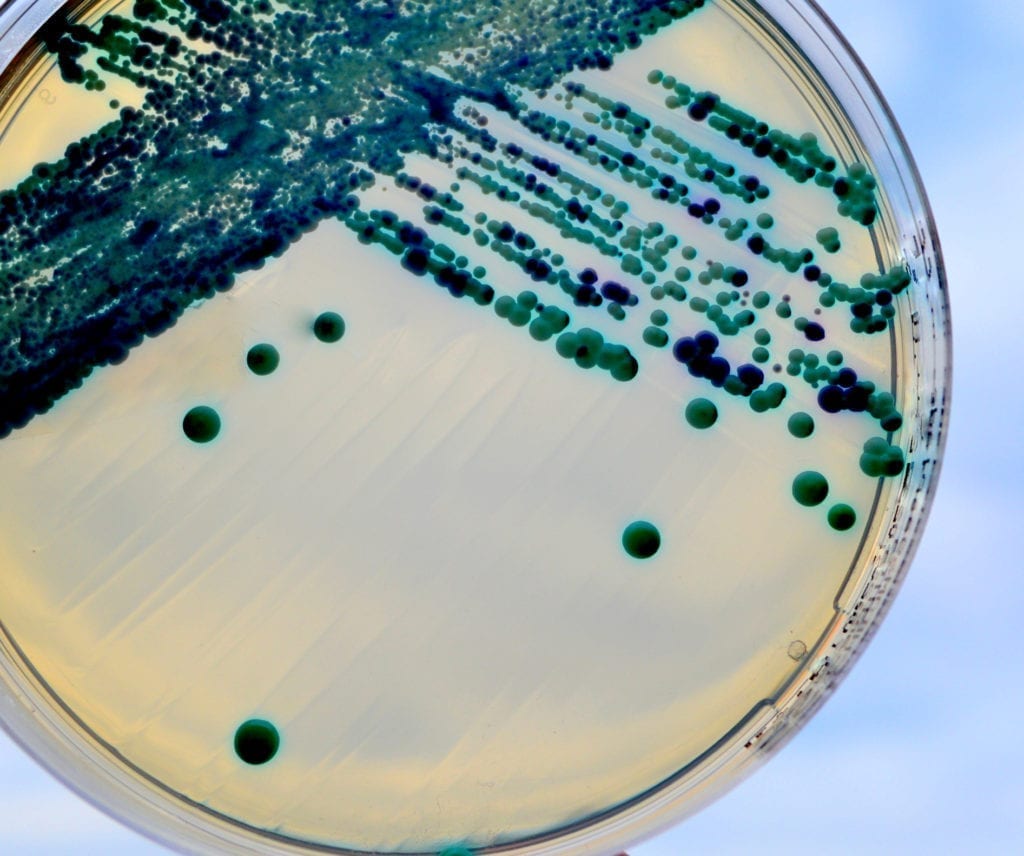

3) How’d you do it? Methods tend to be the most criminally neglected sections of scientific papers: Months, or years, of equipment malfunction and ingenious engineering and dark moments of self-doubt get boiled down to “Parrotfish were sampled at five locations.” Journalists share the blame: We’re pathologically focused on what you found, and sometimes pay only cursory mind to how you found it. Narrative science journalism provides an opportunity to unpack those oft-ignored trials and tribulations.

For the above reasons, I adore the #fieldworkfail hashtag. It delves deep behind the scenes, provides fascinating methodological insight, and displays touching honesty and humanity. I’ve resolved to henceforth ask my sources (or at least those with senses of humor) about their own fieldwork fails. Frightening though it may be, I encourage you to share yours with reporters, too—you’ll find perked-up and sympathetic ears.

All of this said: The aforementioned abolition of gatekeepers means you could cut out the journalistic middleman and write about your own work. No longer do you have to be a staff writer at an elite publication to get your byline before millions of eyeballs; these days, all you need is access to a word processor (a modicum of talent and hard work help, too, of course).

I won’t bother discussing blogging, since nothing I could tell you would be as helpful as simply reading Southern Fried Science or Deep Sea News. Besides, for many reasons—the built-in audience and the thrill of getting paid among them—it’s worth attempting to write for an established media outlet; not immediately, perhaps, but with some practice. (You might try honing your chops on Medium). Lots of sites regularly publish submissions from scientists, among them Nautilus, National Geographic News, Hakai Magazine, Ensia, and Yale Environment 360.

What should you write about? You don’t have to cover your most recent paper—in fact, many editors won’t be interested. The best fodder tends to the inside-baseball stuff. For example, shark scientist David Shiffman wrote a neat little story for Hakai Magazine about how four dead sharks, found by a scuba diver in a ghost net, ended up supporting research at several different labs. That’s a story that no journalist could find—it’s simply not in the literature.

Some practical advice: If you’re considering entering the media fray, I recommend perusing The Open Notebook, a website devoted to the craft of science journalism. Take a stroll through the site’s pitch database, where accomplished science writers have posted their successful magazine pitches, to learn how to query an editor. Also pick up the Science Writers’ Handbook, an invaluable resource that dispenses advice about everything from generating article ideas to crafting a book proposal.

You’ll probably wrack up some rejection letters at first, but don’t get discouraged. Whether you end up sharing your work (in all its nuanced, pathos-rich glory) with a journalist, or writing about it yourself, the world will be richer for having heard your story.

This blog post is part of our Making Waves: The future of #scicomm in fisheries sciences series. For information on the series please read the introductory post.