Last year the article Scientists on Twitter: Preaching to the choir or singing from the rooftops? ranked #38 out of 2.8 million most popular scholarly articles scored by Altmetrics. The paper, published in the open access journal FACETS, has an Altmetrics score of 3460—a value determined by the study’s impact on news, policy, and social media. The paper has been tweeted about over 10,000 times.

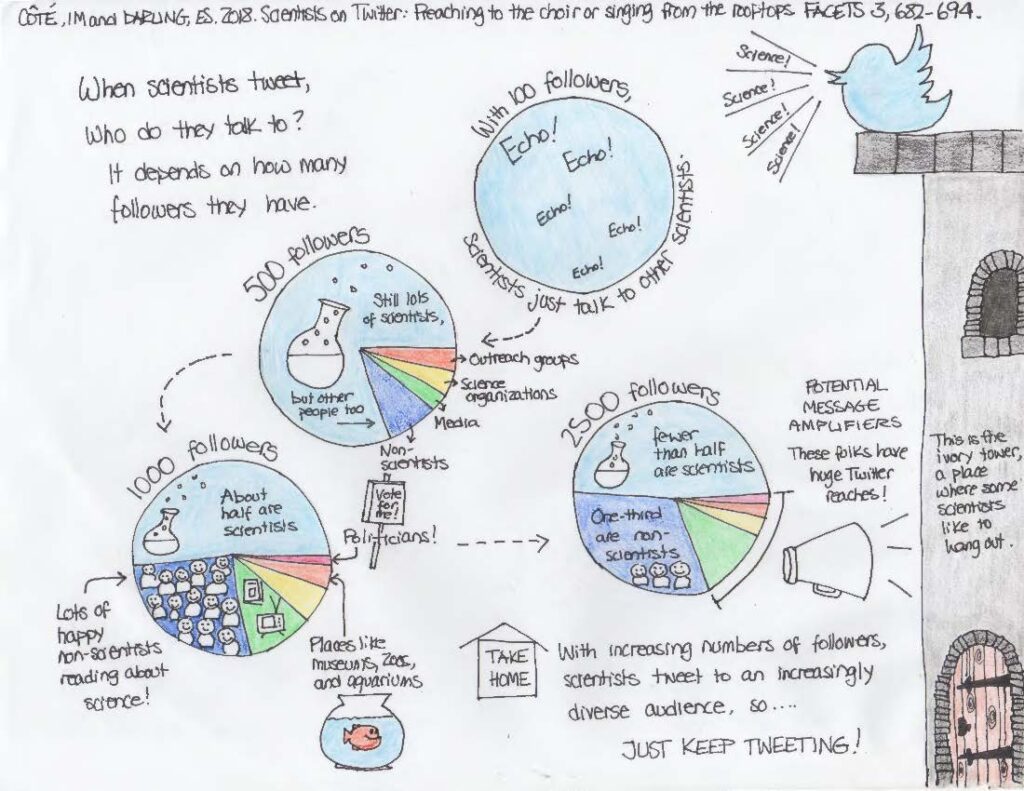

The study sought to determine how many Twitter followers a researcher needs to expand their following beyond other scientists. Although many researchers were aware of Twitter, it was unknown whether their work was reaching beyond the ivory tower and to members of the media, general public, or policy-makers.

By analyzing data from more than 100 scientists on Twitter and their followers, study authors Emily Darling and Isabelle Côté found that beyond a threshold of around 1000 followers, the audience diversity expands well beyond other scientists. The paper concludes that tweeting does in fact have the potential to carry out scientific outreach to a non-scientific audience—researchers just need to keep tweeting.

Emily Darling, Conservation Scientist at Wildlife Conservation Society, and Isabelle Côté, Professor of Marine Ecology at Simon Fraser University, authors of one of the most popular academic articles shared on Twitter. (Photo | Isabelle Côté)

Here, Emily Darling, a Conservation Scientist at Wildlife Conservation Society, and Isabelle Côté, Professor of Marine Ecology at Simon Fraser University, discuss their tremendously popular article and their own experiences and advice on Twitter.

Congratulations on placing #38 on the Altmetrics most popular articles list! Were you surprised when you found out?

Isabelle: Yes. Certainly it was not on my radar—I don’t think it was on Emily’s radar either. We knew it made a bit of a splash, but we might expect that on Twitter about a paper that’s about Twitter.

Emily: Yeah, I think it’s fabulous that we’re starting to value different papers for their impact in lots of different ways—whether that’s an impact in the scientific literature, an impact on society and communication, or an impact on how scientists communicate and value communication. I was certainly surprised too.