Dr. Michael Ryan from the Cleveland Museum of Natural History and his colleagues published a paper in the Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences that describes two new clades. In this post, Dr. Ryan provides some background and context surrounding the formal recognition of these two new tribes of centrosaurine ceratopsids.

Background

The herbivorous horned-dinosaurs (ceratopsians), exemplified by the ever-popular Triceratops, originated from small, bipedal ancestors in the Late Jurassic of Asia. These diversified and evolved into a variety of quadrupedal forms, such as Protoceratops, and eventually migrated to North America by the Turonian (90 million years ago).

From there, in western North America, there was the evolution of the small-bodied leptoceratopsids occurred in parallel as well as the much larger bodied Ceratopsidae which dominated the landscape from the Campanian until the extinction of dinosaurs (except birds) at the end of Cretaceous 66 million years ago.

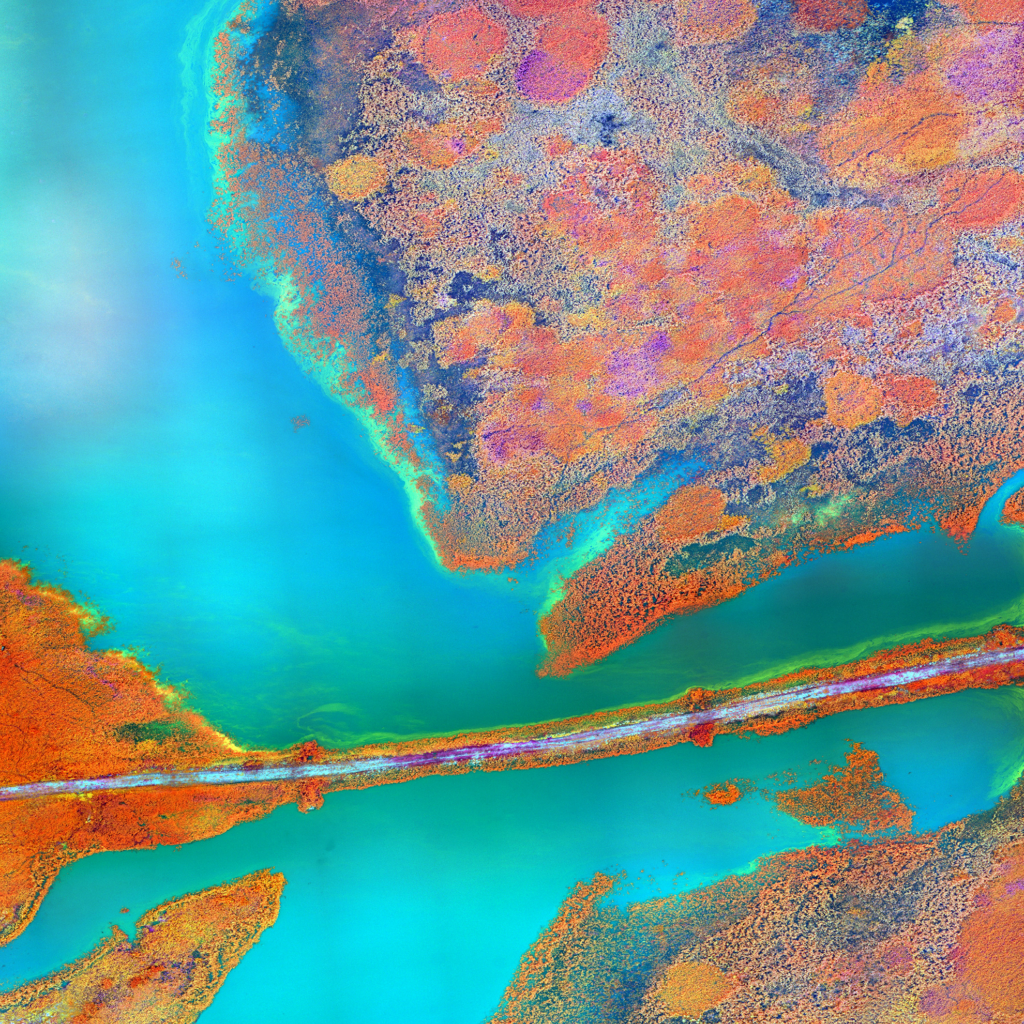

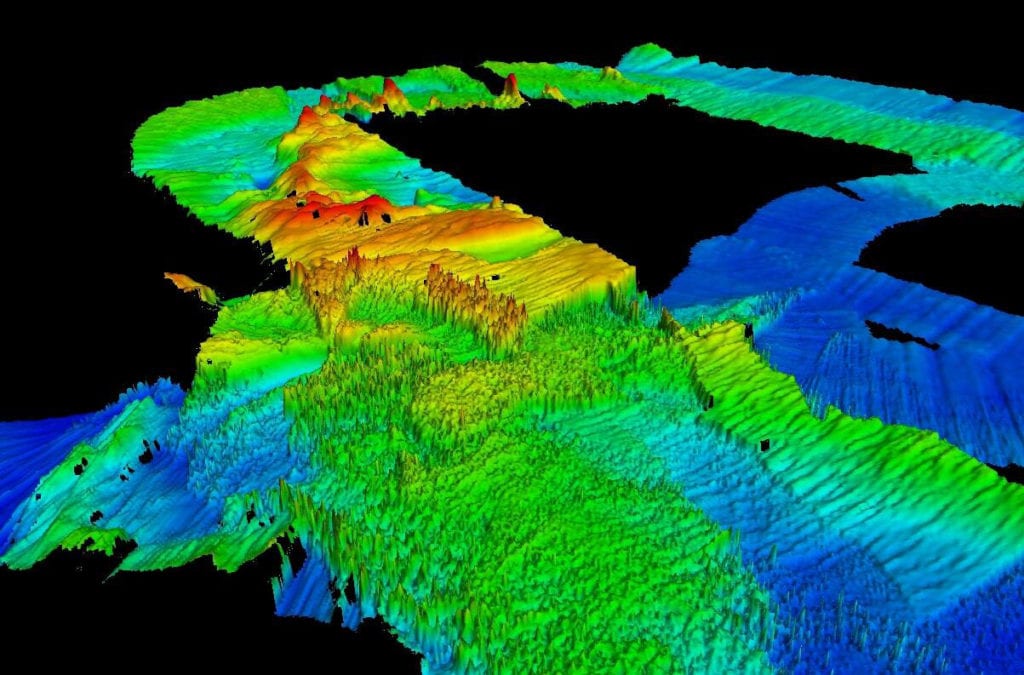

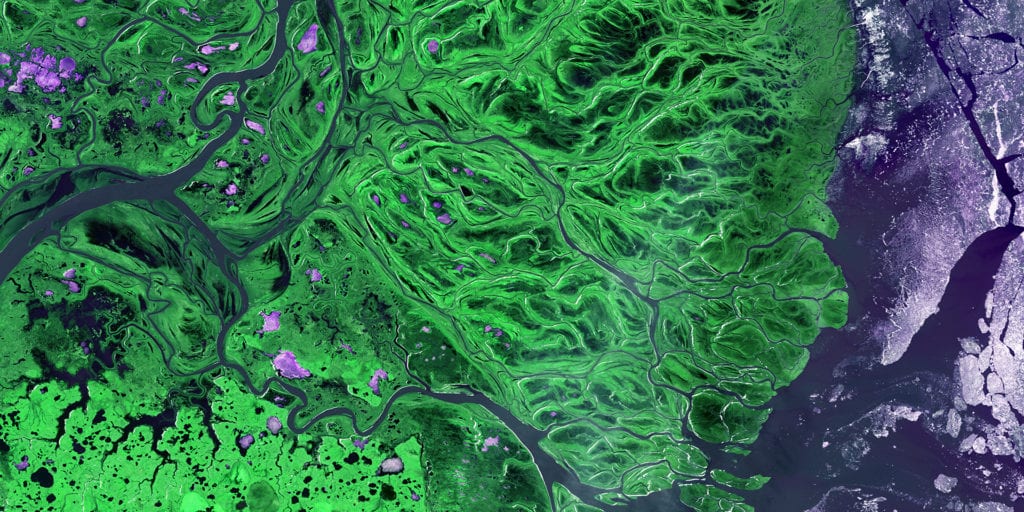

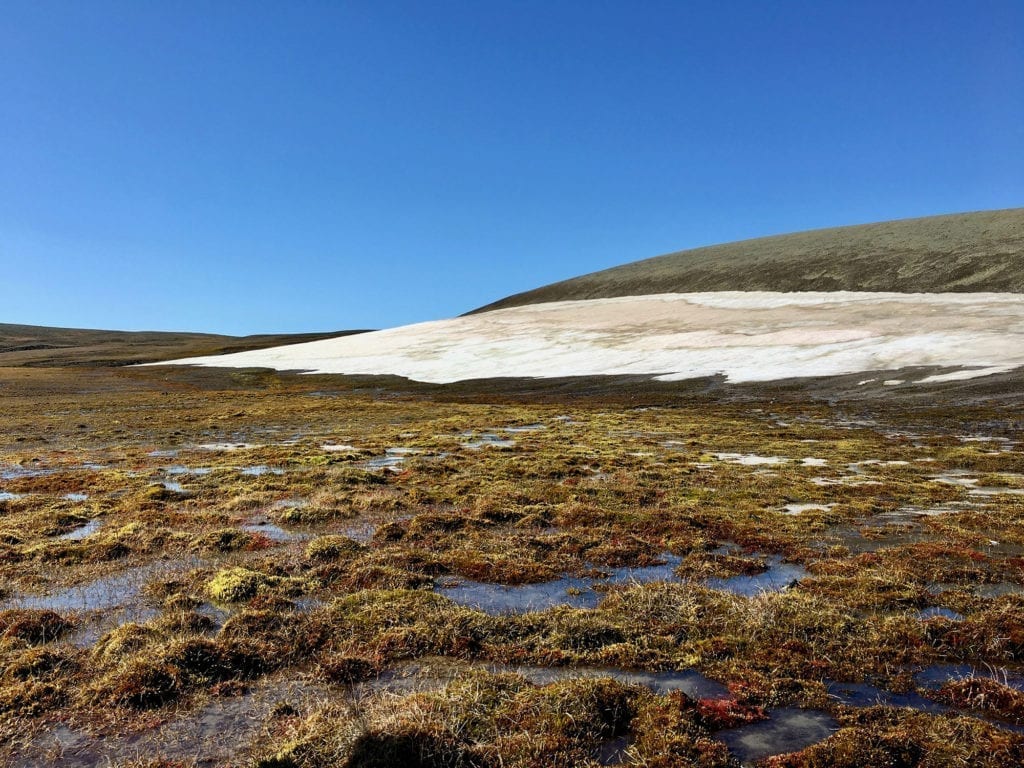

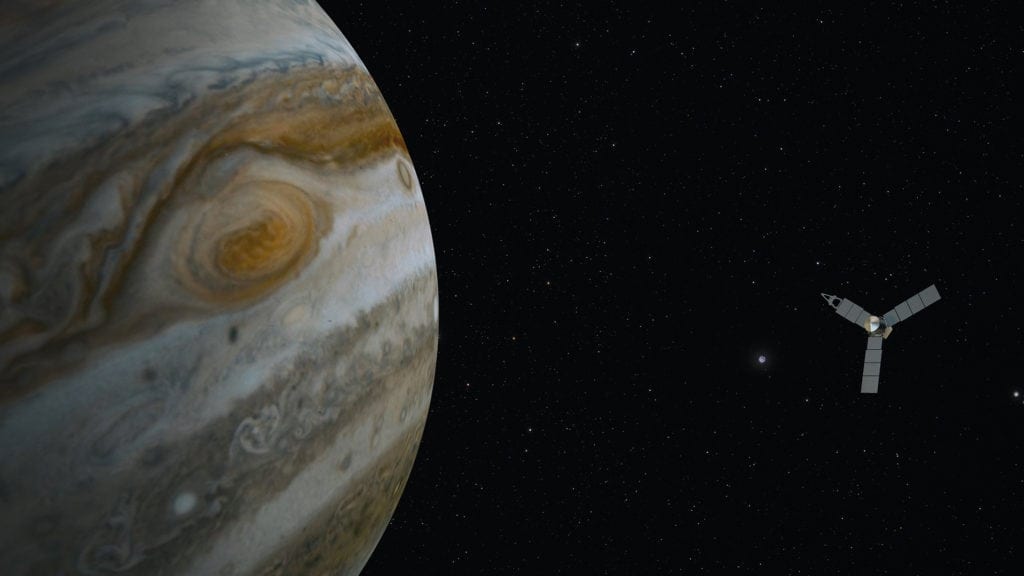

During the Late Cretaceous, North America was divided into two land masses—western Laramidia and eastern Appalachia—by the Western Interior Seaway. Although dinosaurs would have ranged across both Laramidia and Appalachia, the high sediment influx from the rising Rocky Mountains coursing through the bountiful rivers and channels draining into the inland seamade Laramidia a more favorable place to preserve fossils.

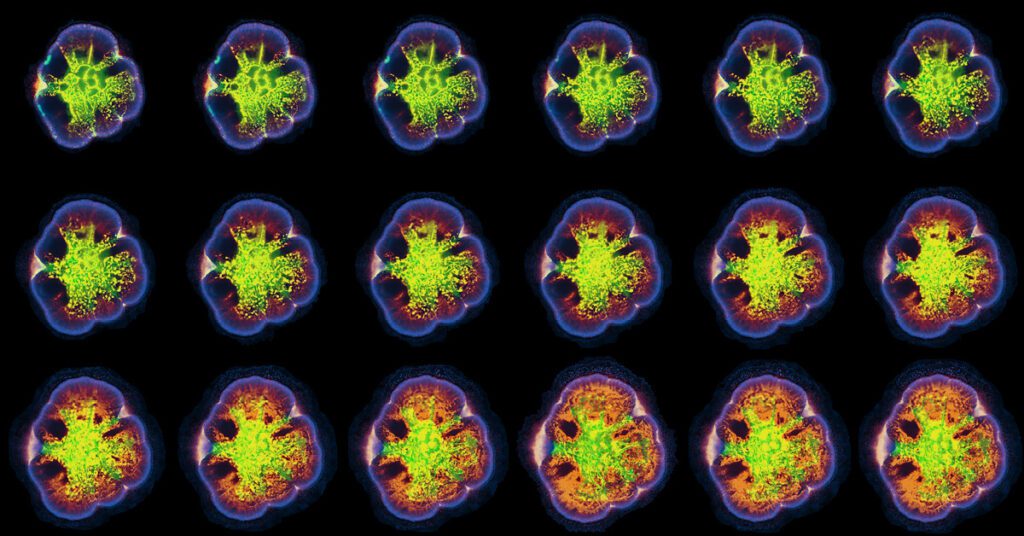

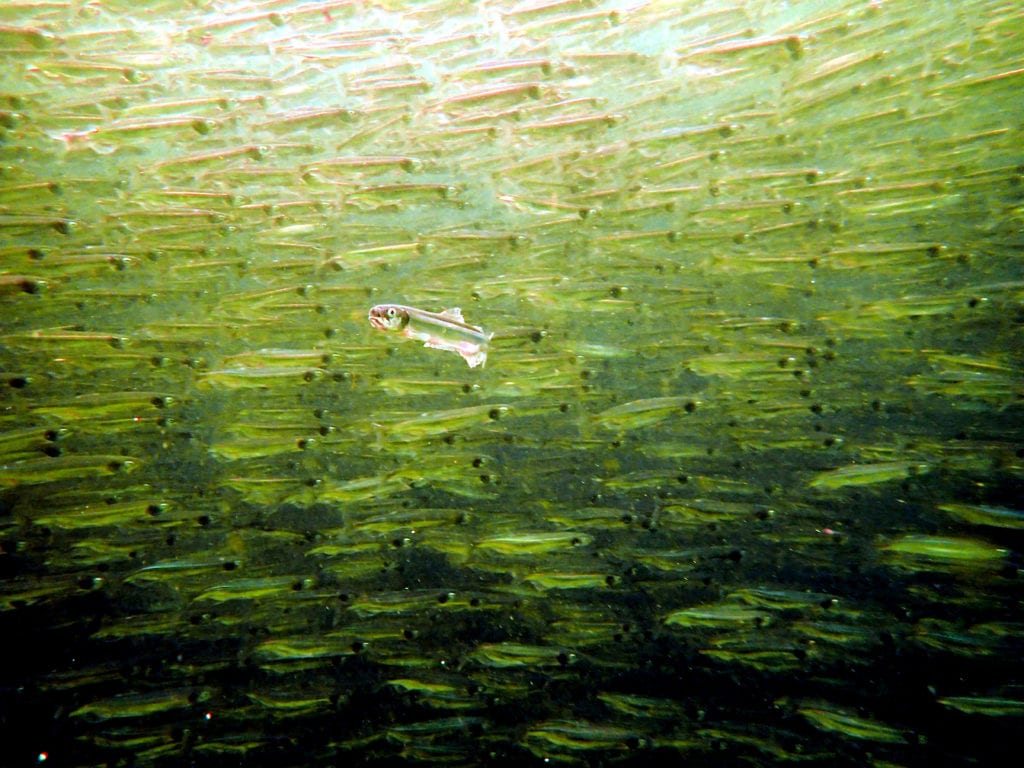

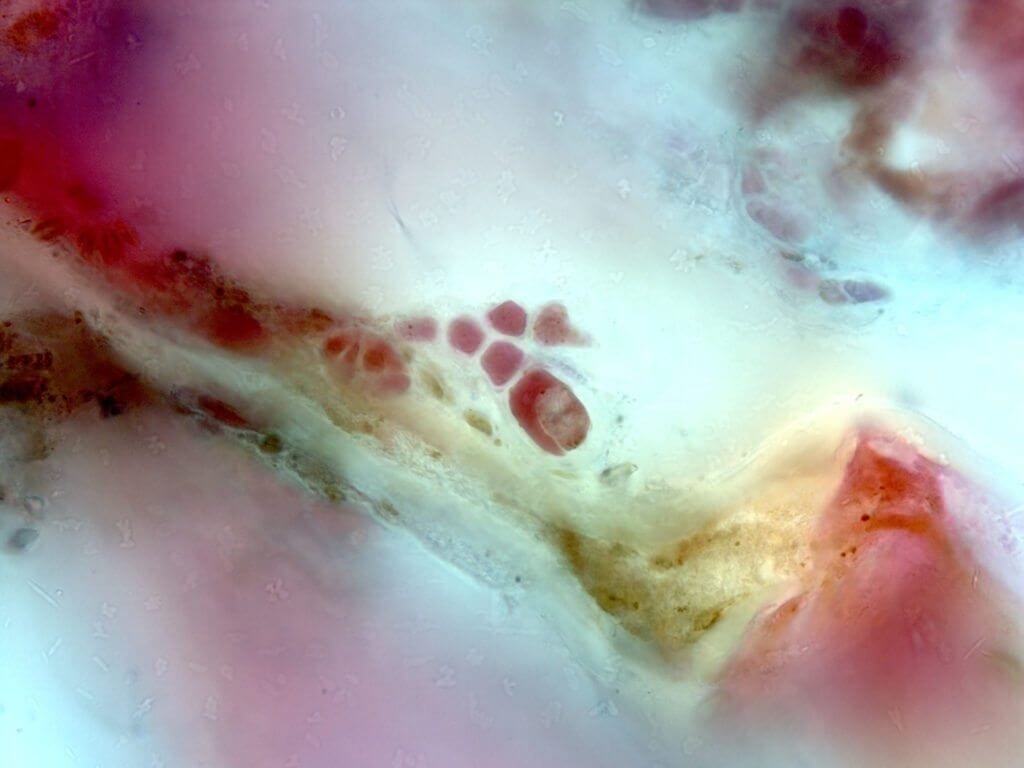

Ceratopsidae is made up of two subfamilies, Centrosaurinae (e.g., Styracosaurus and Chasmosaurinae (e.g., Chasmosaurus and Triceratops. Ceratopsians are one of the most frequently encountered dinosaur fossils from the Late Cretaceous of Laramidia. In the late Campanian deposits of the UNSECO World Heritage site, Dinosaur Provincial Park, near Brooks, Alberta, horned dinosaurs, like ceratopsians, make up approximately one-quarter of all the fossils that have been collected in over the past 100 years. Many of these fossils are found in large bonebeds—mass death assemblages—that typically preserve the remains of only one type of dinosaur with Centrosaurus bonebeds being the most common. All the remains in a bonebed are disarticulated, but they contain elements from all parts of the skeletons, and can represent individuals ranging in age from new-born hatchlings to the largest mature adults. The number of individuals represented in a bonebed can range from dozens to potentially tens of thousands.

Understanding the Evolutionary History of Horned Dinosaurs

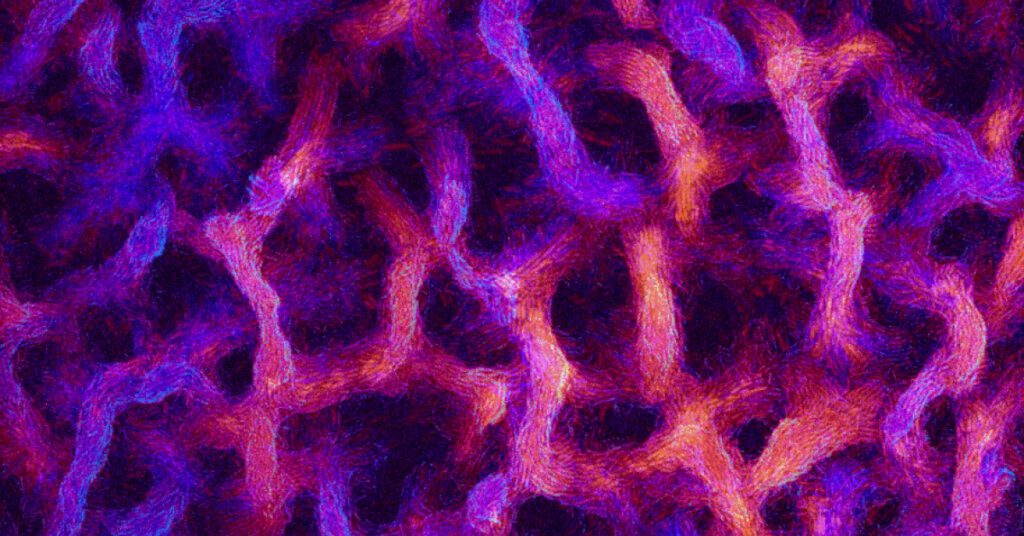

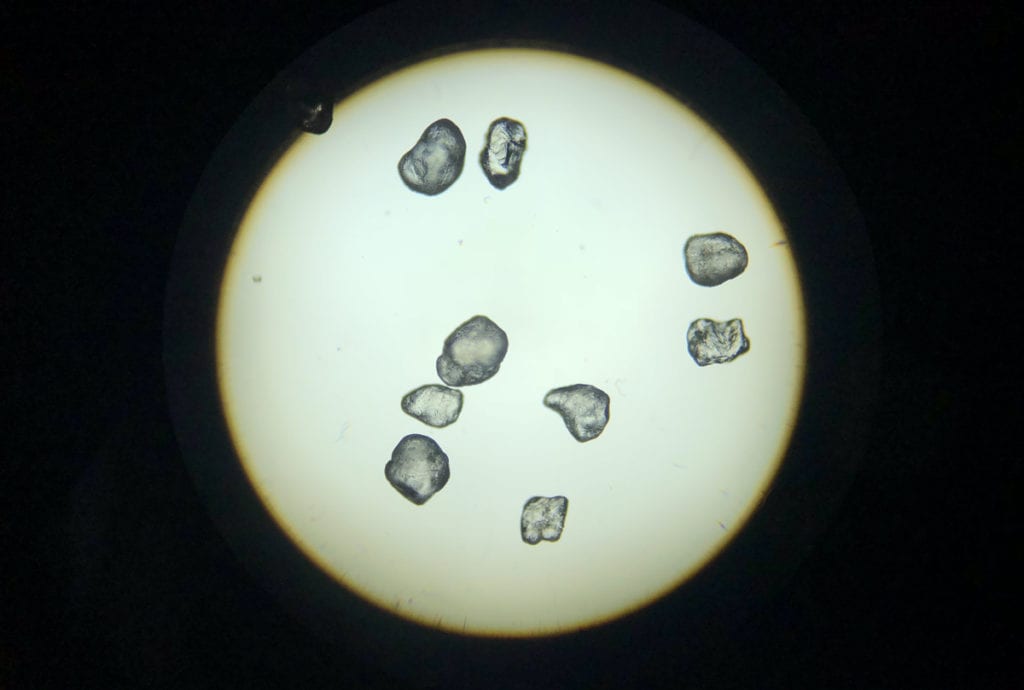

In the last twenty years, our understanding of the diversity and evolutionary history of horned dinosaurs has increased tremendously, with more than 30 new species having been described from Asia and North America. In North America, much of this work has focused on centrosaurine ceratopsids because they have been discovered and collected more frequently than chasmosaurs. All large-bodied ceratopsids have very similar body skeletons. If you were lucky enough to find the headless skeleton of a ceratopsid you’d have to look very carefully at the bones of the upper arm (humerus and ulna) and the pelvis (i.e., the ischia) to even determine which subfamily the skeleton was from, and determining the genus or species would be almost impossible. The defining characteristics for centrosaurs are in the ornamentation on the skull: the nasal horn over the nose, the postorbital horns over the brows, and the unique development of hooks orspikes along the margin of the elongate frill behind the skull. The frill is composed of three bones—the parietal from the top of the skull, and the paired squamosals from either side. The frill ornamentation formed through the modification of small bones (epimarginals) that developed in the skin covering the edges of the frill, much like the bony scutes that develop down the backs of modern crocodiles. By contrast to the centrosaurs, many chasmosaurs can be defined by the unique architecture of the premaxilla that make up most of their nose.

Recognizing New Tribes of Centrosaurine Ceratopsids

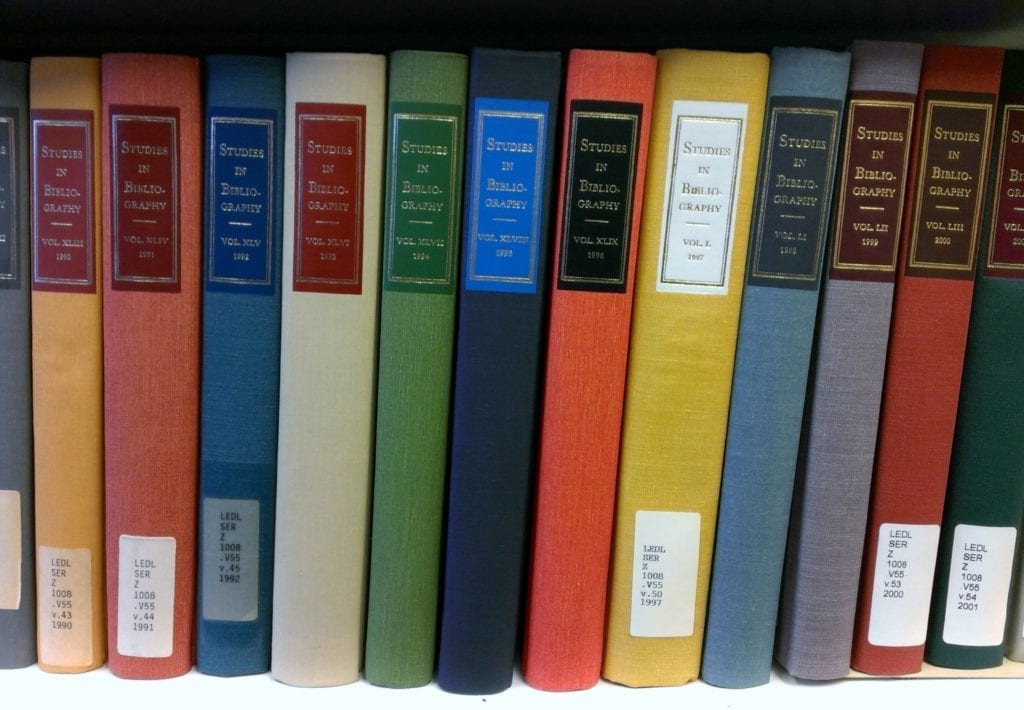

Thanks to the work of a number of institutions and groups, including my own Southern Alberta Dinosaur Project that I co-lead with Dr. David Evans of the Royal Ontario Museum, we now have a fairly complete map of the evolutionary history of centrosaurine ceratopsids, and, with the new research published today in the Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences, we’ve now been able to recognize two new tribes of centrosaurine ceratopsids, Nasutoceratopsini and Centrosaurini, in addition to the previously described tribe Pachyrhinosaurini.

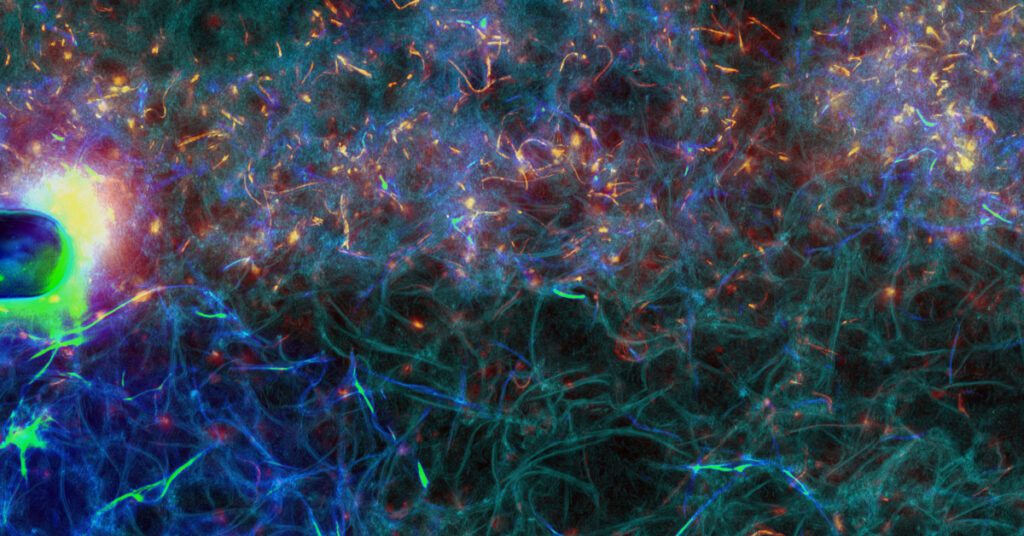

The earliest members of the Centrosaurinae are not formally assigned to a tribe. These basal members include taxa such as Diabloceratops from the Wahweap Formation of Utah (southern Laramidia) and Xenoceratops (described in A new ceratopsid from the Foremost Formation (middle Campanian) of Alberta from the Foremost Formation of Alberta (northern Laramidia). These centrosaurs are characterized by having little to no elaboration of the nasal horn, long, robust postorbital horns (a primitive characteristic also seen in the nearest relatives to Ceratopsidae—Turanoceratops from Uzbekistan and Zuniceratops from New Mexico), and frills with distinct spike-like epimarginals at the corners of the frills. These taxa are found in rocks much older than the younger centrosaurs of the newly recognized Centrosaurini (all the centrosaurs discussed further, unless otherwise noted, are from Alberta), such as Coronosaurus, Centrosaurus and Styracosaurus, that have well-developed, erect nasal horns, much shorter postorbital horns, and more elaborate ornamentation on the frill. Styracosaurus takes all of these horn modifications to extremes by sporting one of the longest nasal horns of any centrosaur, the complete reduction and loss of the postorbital horns in adults, and the longest spikes on any of the frills.

Styracosaurus is known from the top portion of the Dinosaur Park Formation in Alberta. This formation is conformably covered by the marine Bearpaw Formation deposited by the transgressing Western Interior Seaway. As the seaway encroached on the area that is Dinosaur Provincial Park, ~74 millions of years ago, Styracosaurus went extinct and was replaced by the first of the pachyrostran centrosaurines (e.g., Pachyrhinosaurus) that will be the only centrosaurine ceratopsids (Tribe Pachyrhinosaurini) left once the seaway retreats and the interior on North America drains, finally uniting Appalachia and Laramidia into one continental landmass at the end of the Cretaceous. These centrosaurs take cranial ornamentation modification to the extreme by replacing the nasal and postorbital ornamentations with large pachyostotic bosses in the adults; their frills retain two pairs of spikes on the back margin of their frill. The centrosaurs go extinct in the early Maastrichtian and are ecologically replaced by massive chasmosaurines, the last of which is Triceratops.

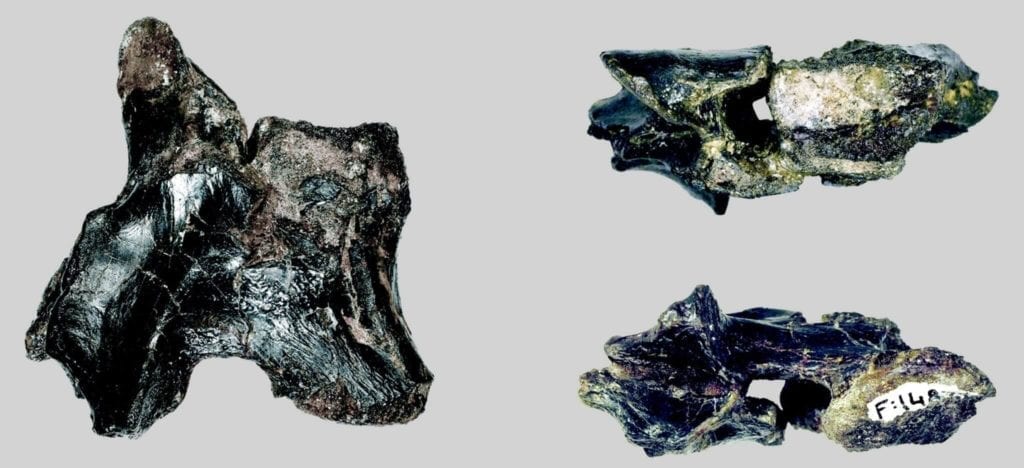

Our new research has also recognized the new tribe Nasutoceratopsini that is phylogenetically basal to Centrosaurini. The new tribe is named after Nasutoceratops, a recently described centrosaur from the Wahweap Formation of Utah. The new tribe was recognized as part of research I began more than 15 years ago looking at a partial skull collected in Alberta in 1937 by the famous Canadian paleontologist, Charlie Sternberg of the Geological Survey of Canada. The specimen was confusing because, although the frill clearly identified it as a centrosaur, it had long postorbital horns. At that time, none of the basal centrosaurs with long postorbital horns, such as Albertaceratops, had yet been discovered, so placing the specimen in a phylogenetic context was problematic. It also lacked any diagnostic frill ornamentation to help identify it, so I set it aside as a project for another day. With the identification of Nasutoceratops, it became clear that CMN 8804 belonged to another distinct tribe of centrosaurs that are united by having a frill lacking modified epimarginals, a small nasal horncore, large, rostrolaterally directed postorbital horncores, and, a relatively short, deep face.

Although the CMN 8804 taxon closely resembles Nasutoceratops, its fragmentary nature prevents it from being named. The presence of the CMN 8804 taxon in Alberta, and the approximately contemporaneous Nasutoceratops in Utah, indicates that the nasutoceratopsins persisted in both north and south Laramidia well after the first appearance (i.e., Coronosaurus of the newly defined Centrosaurini.)

The rarity of avaceratopsins in the well-sampled sediments of Laramidia suggests that they may have had different ecological preferences than centrosaurins, or that their relatively non-diagnostic, fragmentary remains may be misidentified as other centrosaurins. The temporally (~78-74 Ma) and geographically (Utah to Alberta) large distributions of Nasutoceratopsini weakens the hypothesis of distinct north and south Laramidian provinciality.

Dr. Michael J. Ryan is Curator and Head of the Department of Vertebrate Paleontology at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, and an Adjunct Research Professor in the Dept. of Earth Sciences at Carleton University in Ottawa where he did his B.Sc. Ryan’s research focuses on the evolution and paleobiology of Late Cretaceous dinosaurs with an empathize on Ceratopsia, the horned-dinosaurs. He is co-leader of the Southern Alberta Dinosaur Project that has described more than 10 new dinosaurs in the past decade. He has conducted field work around the globe including, Africa, Argentina, Canada, Greenland, Mongolia, and the USA.