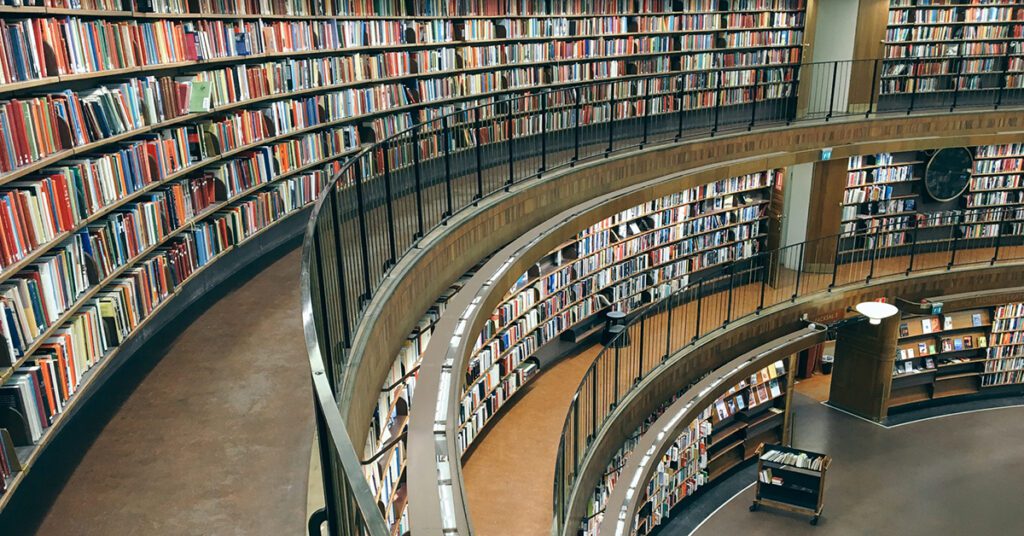

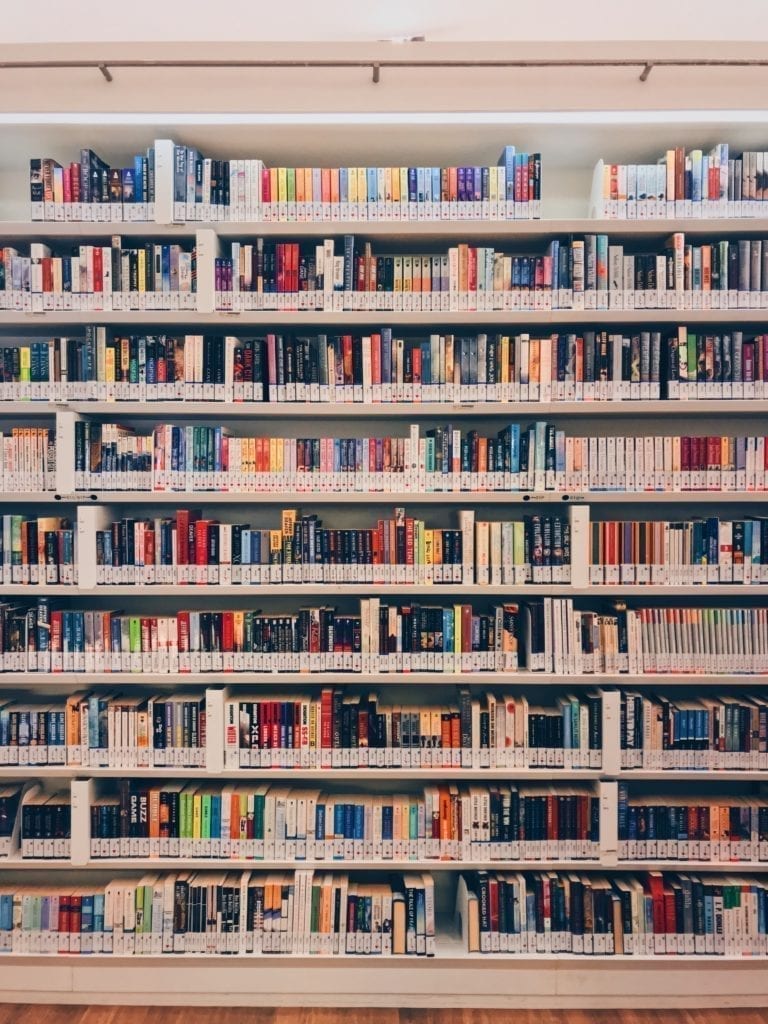

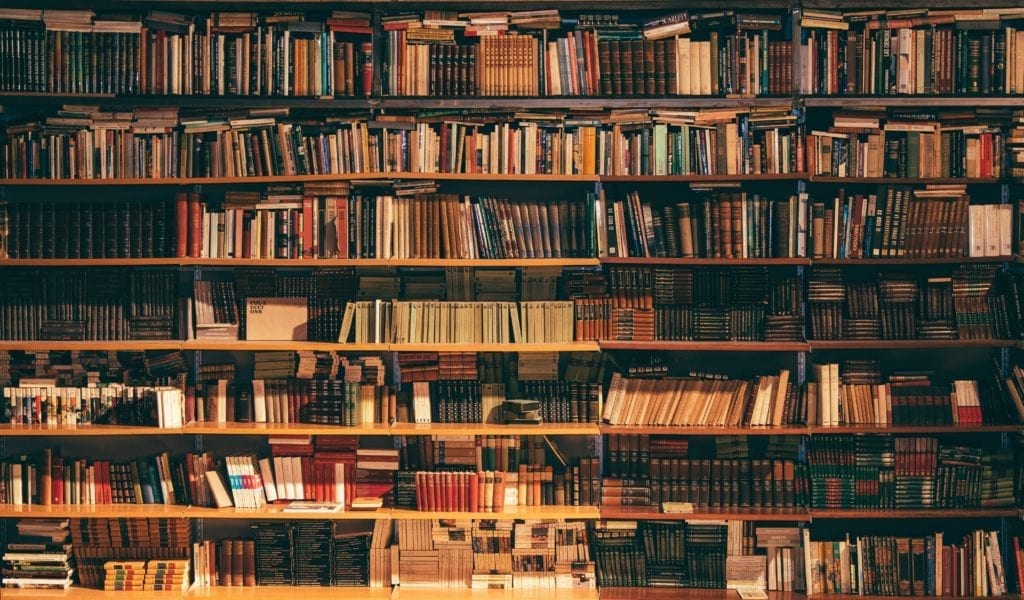

Libraries on university campuses are so much more than a quiet place to study. I, a scientist, am quickly learning all a library has to offer with each visit to the Leddy at the University of Windsor.

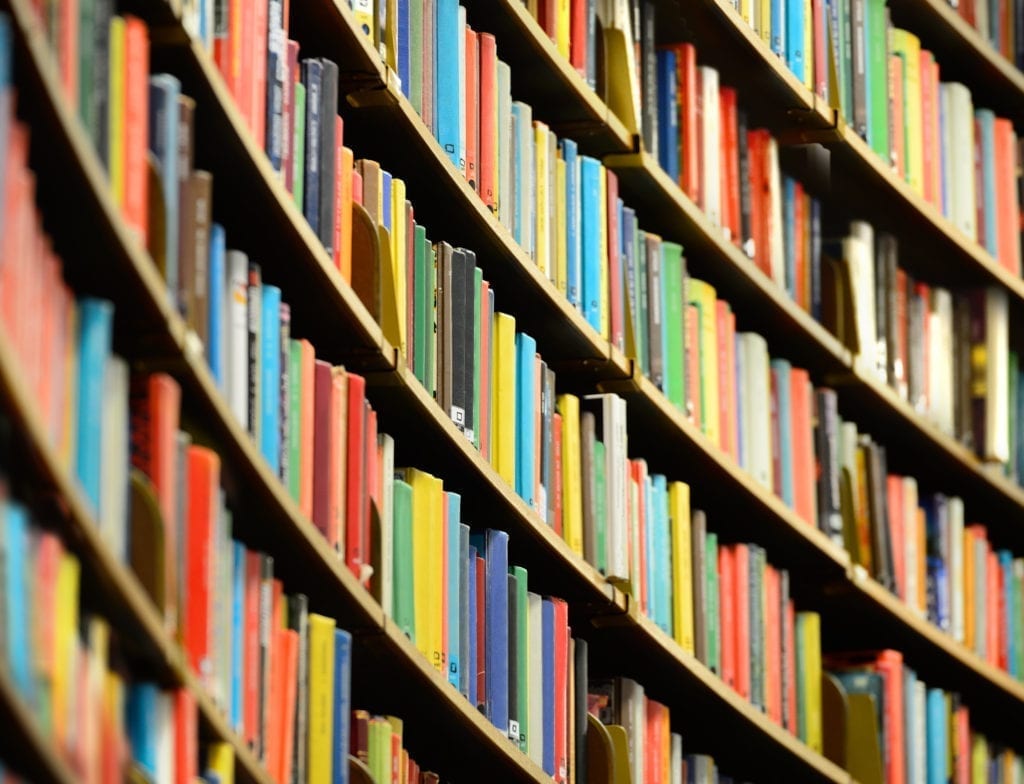

Libraries connect scientists to history – history of modern science, history of a specific field of study, or history of a study organism. Libraries are conduits of creative thinking. A solid knowledge base is a scientist’s reservoir for spawning new ideas. Libraries of course have the physical sources for one to expand their understanding on a given subject. Libraries can also be the setting for any of the stages of the classic, four-stage model of the creative process: preparation, incubation, illumination, and verification. Libraries are also a dwelling for scientists to channel their inner artist.

Continuing onward through the Library Nexus blog series, we have arrived at the intersection among library, scientist and art. The relationship between scientist and artist is one typically understood to be opposing: scientists are boringly methodical and generate facts, whereas artists are passionately creative and generate art. I believe that scientists possess attributes of artists, and artists possess attributes of scientists. Both vocations demand creativity and an open mind. Both vocations ask questions, seek answers, and innovate.

How does a library fit into this pairing of scientist and artist? Art galleries and museums are traditional homes for art. But library collections also encompass different categories of the creative arts, and libraries themselves are works of architectural art. So how does a scientist extract artistic meaning from the collections at a library? For this post I focused on two forms of art offered through libraries that have the potential to shape scientific and creative thought: illustration and poetry.

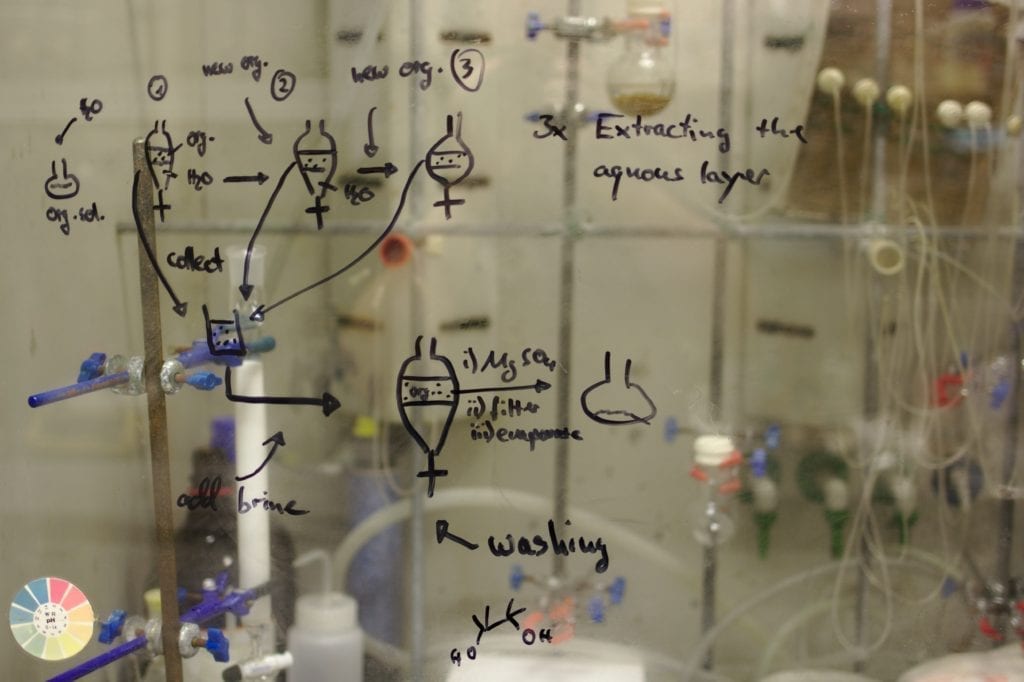

Illustration

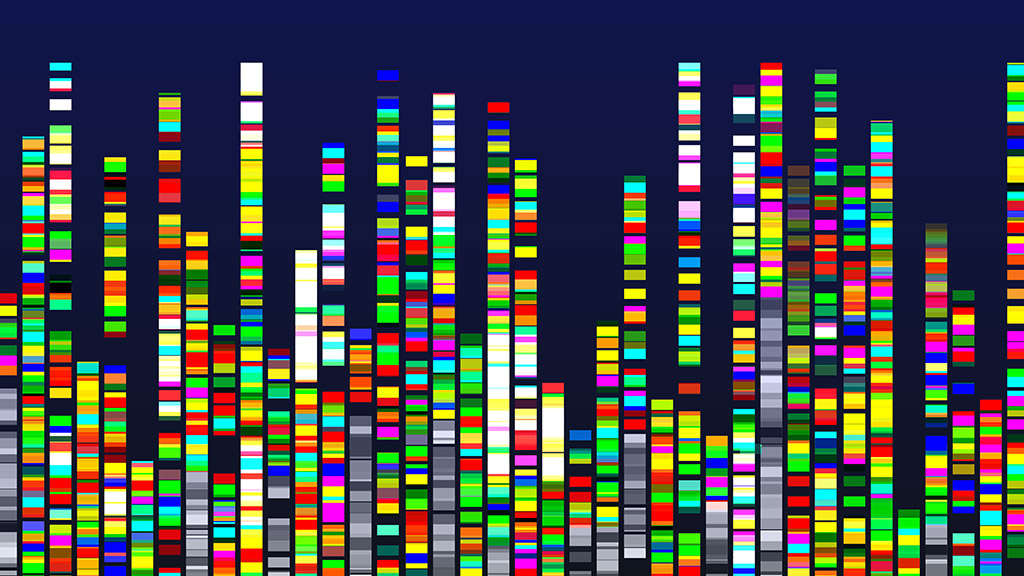

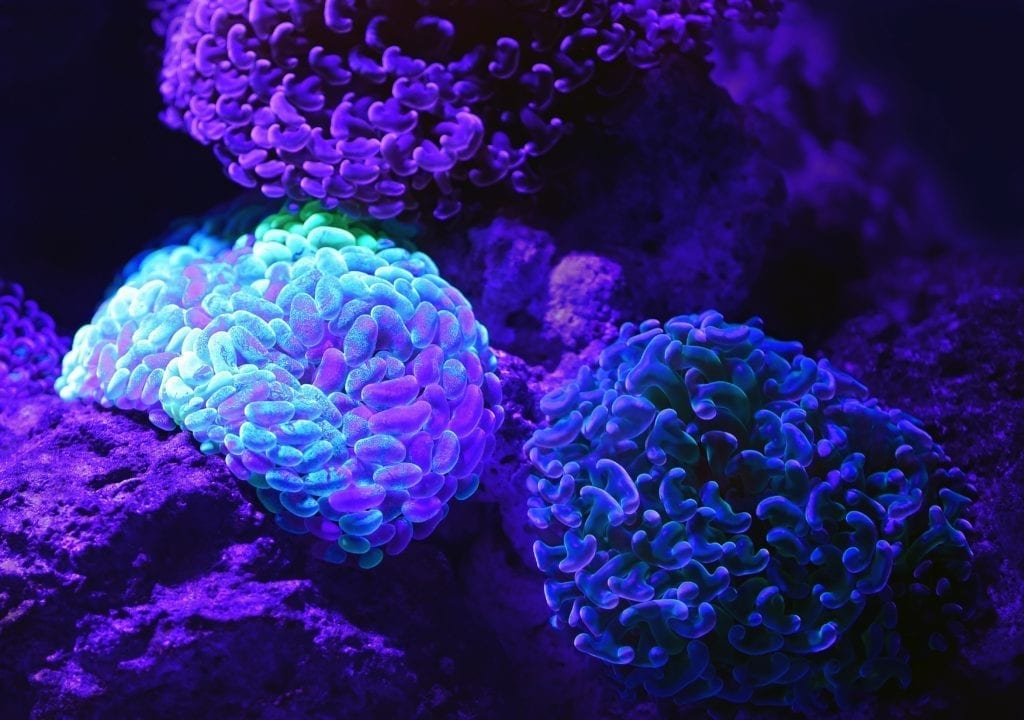

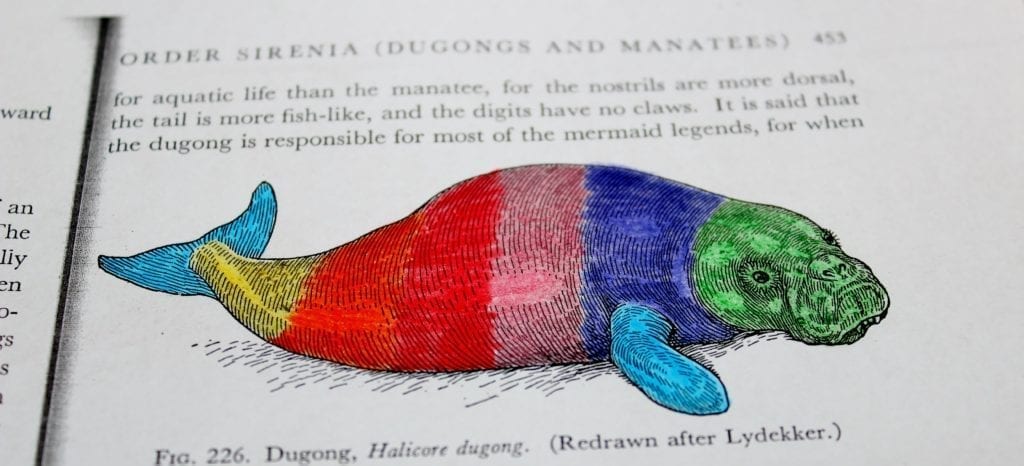

Some time ago Twitter brought to my attention #ColorOurCollections. This #sciart initiative, led by numerous institutions including the New York Academy of Medicine, Biodiversity Heritage Library and Smithsonian Libraries, encourages the colouring of images from library collections. Of course you are not supposed to wreak havoc on the original pages of a library’s stock. The participating institutions provide free, black and white images that you can download, print and colour. Like the objective of this blog series, #ColorOurCollections broadens one’s perception on what a library is and has to offer. Libraries are certainly a “creative resource”, and this notion becomes even more evident when libraries “heighten the visibility of and access to” content that would not normally be browsed by non-specialists.

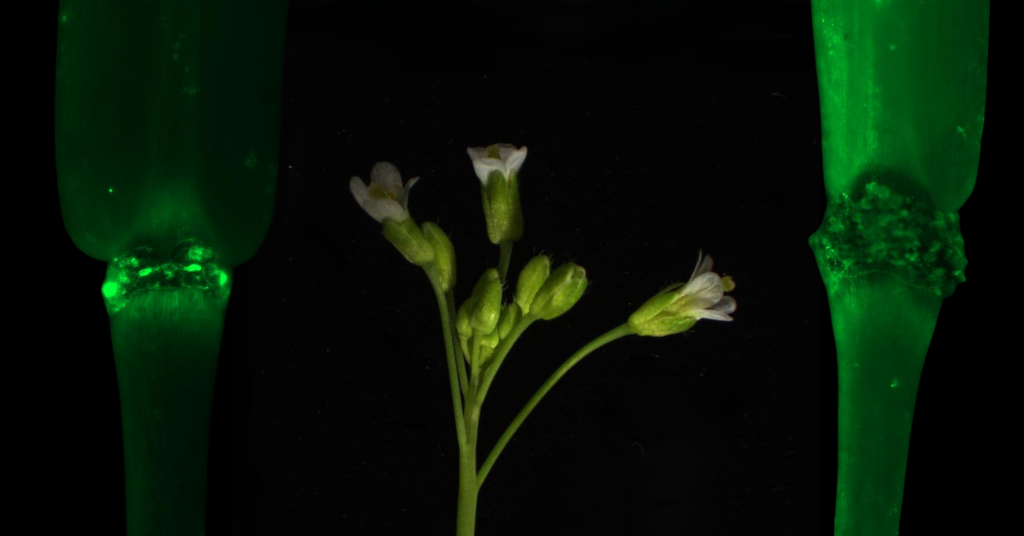

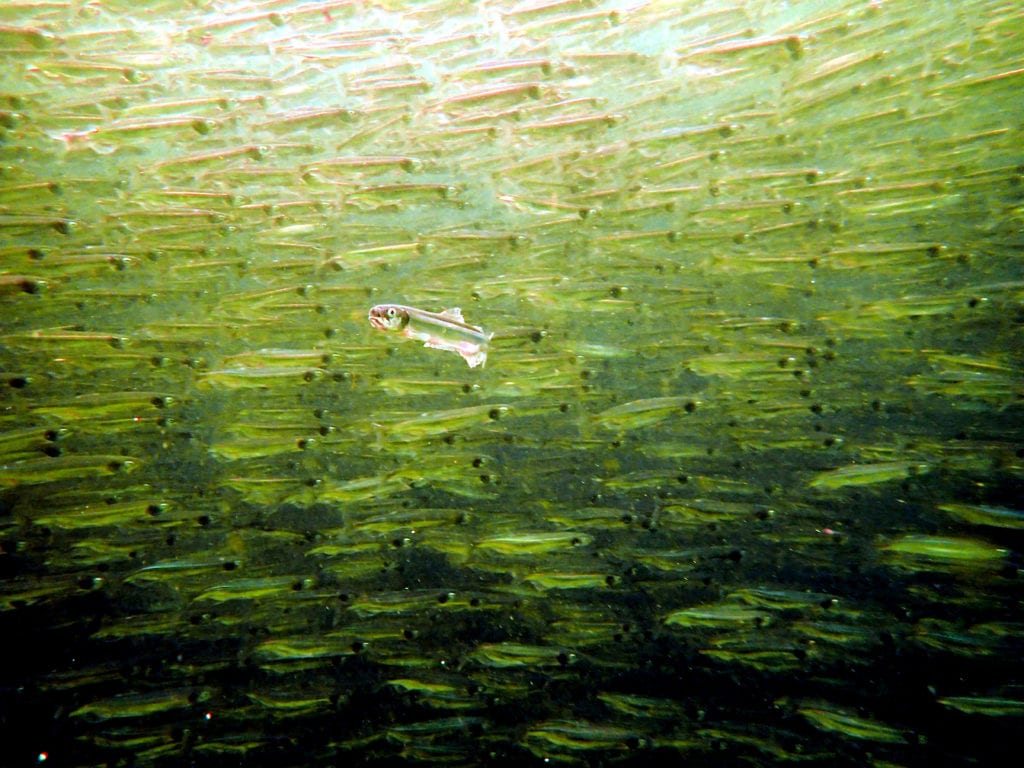

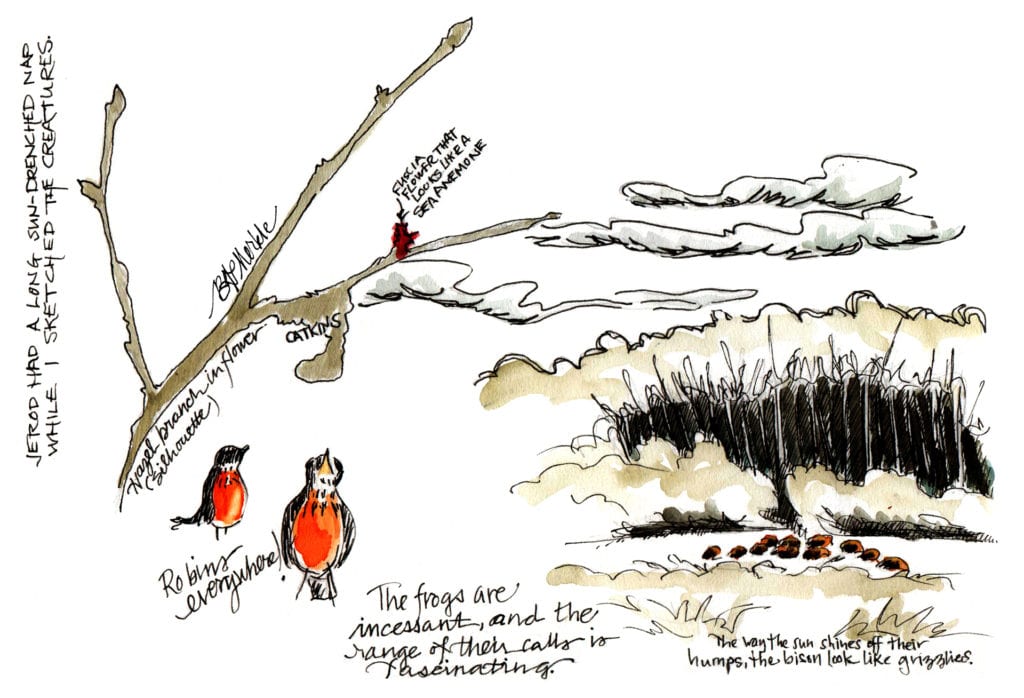

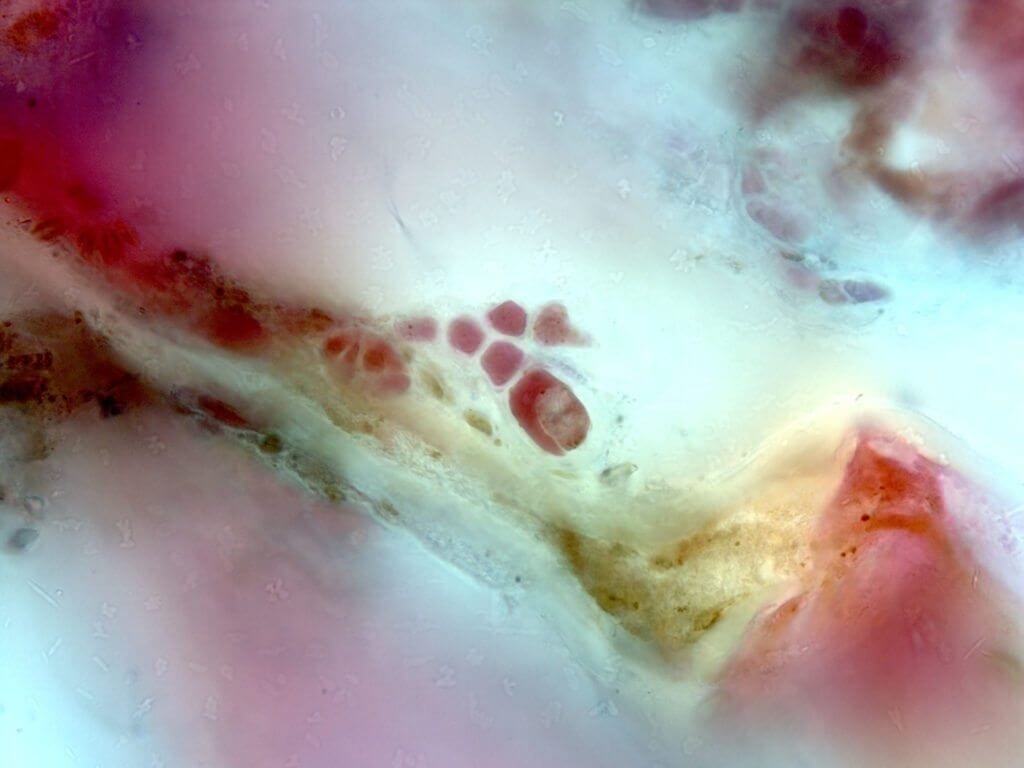

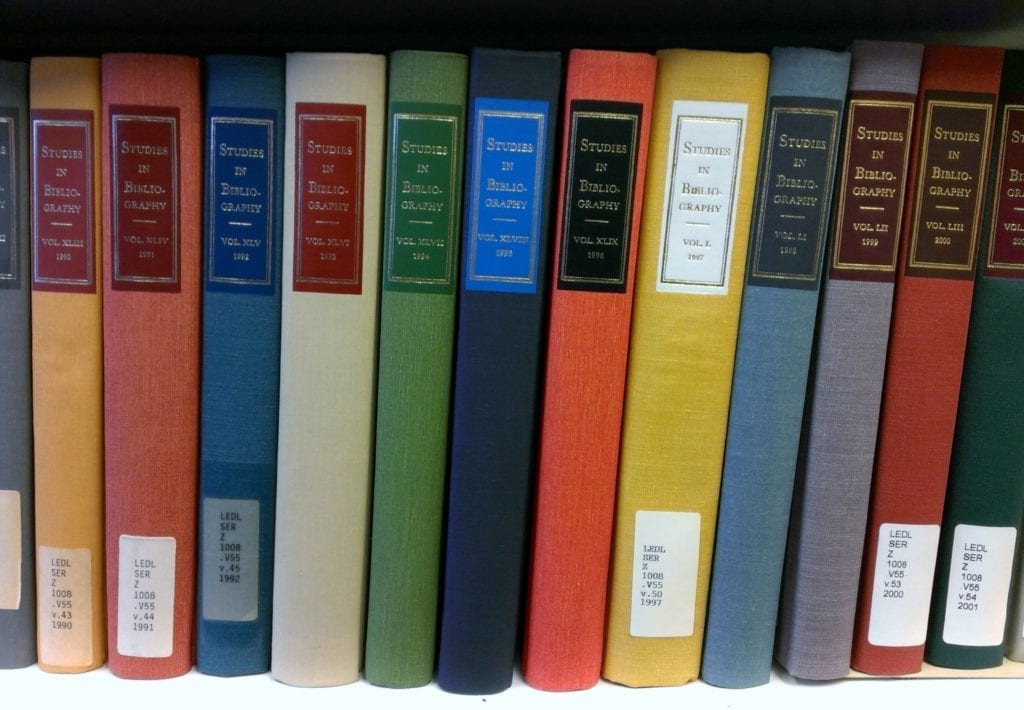

I headed to Leddy to see what colourless images I could find and bring chromaticity to. I made my way to the natural history texts. I skimmed the botanical field guides, which were rich with monochrome images patiently awaiting to be adorned with shades of green.

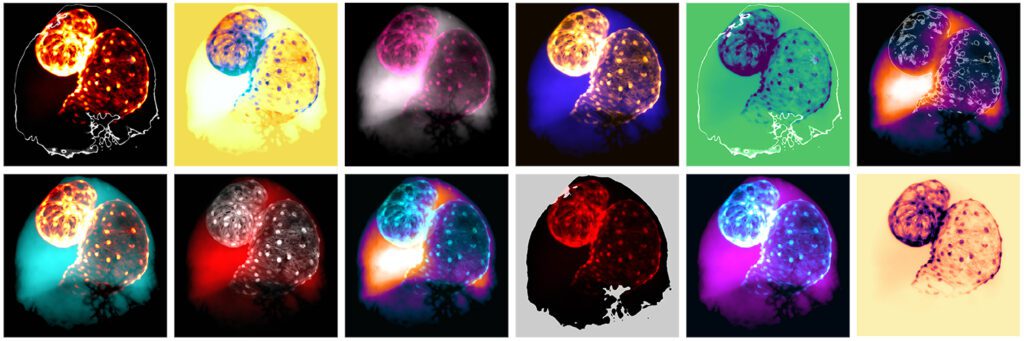

There were drawings in The Fishes of Uganda that I envisioned being drenched in blue. To branch away from my teleost tendencies I selected the 1955 publication, The Natural History of North American Amphibians and Reptiles. There are a series of pie graphs in this text summarizing the diet of mudpuppy, salamanders, frogs, turtles, and snakes. Although generally abhorred by scientists, these pie graphs were clean, whimsical and called to my coloured pencils. I made photocopies of the images, found a sunny spot in Leddy and coloured. Similar to scientific ventures, the technique I employed was refined with repetition. H.H. Newman’s 1939 The Phylum Chordata provided many options to cultivate my colouring style. I was most pleased with a dugong emboldened with rainbow hues. I couldn’t remember the last time I coloured in such a thoughtful manner. I have, to date, avoided purchasing one of the many alluring, adult colouring books.

This colouring session was definitely cathartic. Not necessarily in the way folks praise colouring mandala patterns, but because, as a scientist, I was able to exercise a process familiar to me to create art (albeit art that may appear identical to that which is boxed away under the stairwell of my childhood home): I sought out a primary resource, learned new knowledge and generated a piece of work I would share with others. I was able to exercise my creativity, which is always a good thing.

Grab the highlighters from the desk drawer and head to the campus library for your own colouring sojourn.

Poetry

I am trained as a scientist. I do not have formal training in poetry. I am, however, intrigued by the connections between science and poetry, the influence of science on poetry and explaining science through poetry.

This curiosity was earnestly sparked during my undergrad when a professor shared the abstract of a paper about sibling rivalry in suckling pigs – it was a rhyming poem! I have read enlightening articles online on these connections (e.g., The science of poetry, the poetry of science, The Scientist and the Poet). I had not yet gone to the library to see how these connections were reflected upon in print, and which scientists, poets and poet-scientists aroused this reflection. Leddy Library has aisles upon aisles of poetry. On the influence of science on poetry I found Ralph B. Crum’s book from 1931 “Scientific Thought in Poetry”.

Turns out the interconnectedness of poetry and science has been pondered for some time. In his opening chapter, Crum reviews the co-occurring perspectives on the two disciplines: “science and poetry are mutually exclusive”, “science and poetry are inimical to each other”, science and poetry are “complementary”. I’m in the third camp – the two are complementary. Yes, there are conspicuous differences between poetry and science, for example, diction. But the underlying motivation of the two is shared – to reveal truths about natural phenomena. As Alison Hawthorne Deming succinctly states, poetry and science “are kindred in their creative process.” Other facets of the two I now see on a spectrum. Take open-mindedness and uncertainty – both are entailed of science and poetry, however, the extent to which these states are embraced by peers is conceivably greater in the literary arts.

Crum later introduced me to poet-scientists. Erasmus Darwin, Charles Darwin’s grandpa, was a physician with a green thumb. The latter affection he expressed poetically in “The Loves of the Plants”. Johann Wolfgang Goethe was a poet, and also keenly studied plants, anatomy and colour. According to Goethe, “science has developed out of poetry.” Alfred Tennyson, deemed “the poet of science”, was a poet interested in and also conflicted by the natural sciences. He wrestled his discourse between religion and science, in part, through poetry.

Poetry need not only be a part of the history of science, but also present-day science. I don’t foresee peer-reviewed journals publishing poems but I do think poetry can be an engaging and effective communication medium of science – all of its inspirations, findings and discords. Poetry is already being used to teach science in the classroom. Gatherings of scientists and poets yield bidirectional learning opportunities. These library visits affirmed to me that science and poetry can be, and indeed are, thoughtfully and respectfully coupled.

As the theoretical biologist Arthur Winfree stated in 1964, the “fruitful combination of poetic and scientific outlooks in a single individual was fortuitous in the past, today it urgently needs to be cultivated.” And today, over 50 years later, I agree. Perhaps, instead of reading the Google Scholar emails in our inboxes during breakfast, we can indulge in poetry.

As with my previous visits to Leddy Library, I did not know what to expect heading to the library with a particular writing goal in mind. Yet, each time I left Leddy with new information filling up my brain (a.k.a., my creativity fuel tank), new approaches I wanted to incorporate into my science communication, and ultimately, new reasons to return to the library. As scientists, and humans, we are entrenched with pursuing curiosities of the natural world. When this pursuit is obstructed or grows stagnant, libraries can be a vehicle to move your scientific thought and communications forward.

Scientists, let’s try stepping away from the comfort zone of our offices, the hypnotizing glow of our laptops, and head to the library. Your coffee can come with you too!