Q&A with Bethann Garramon Merkle

When was the last time you exercised your creativity muscles? For me it was coming up with a new way to administer allergy medication to my cat that didn’t end with her defiantly coughing it up. As it turns out, she will happily accept anything coated in coconut oil. Sometimes it’s not obvious when we’re practicing our creativity. But creativity is a practice, according to Bethann Garramon Merkle, Director of the Wyoming Science Communication Initiative and member of the FACETS Editorial Board.

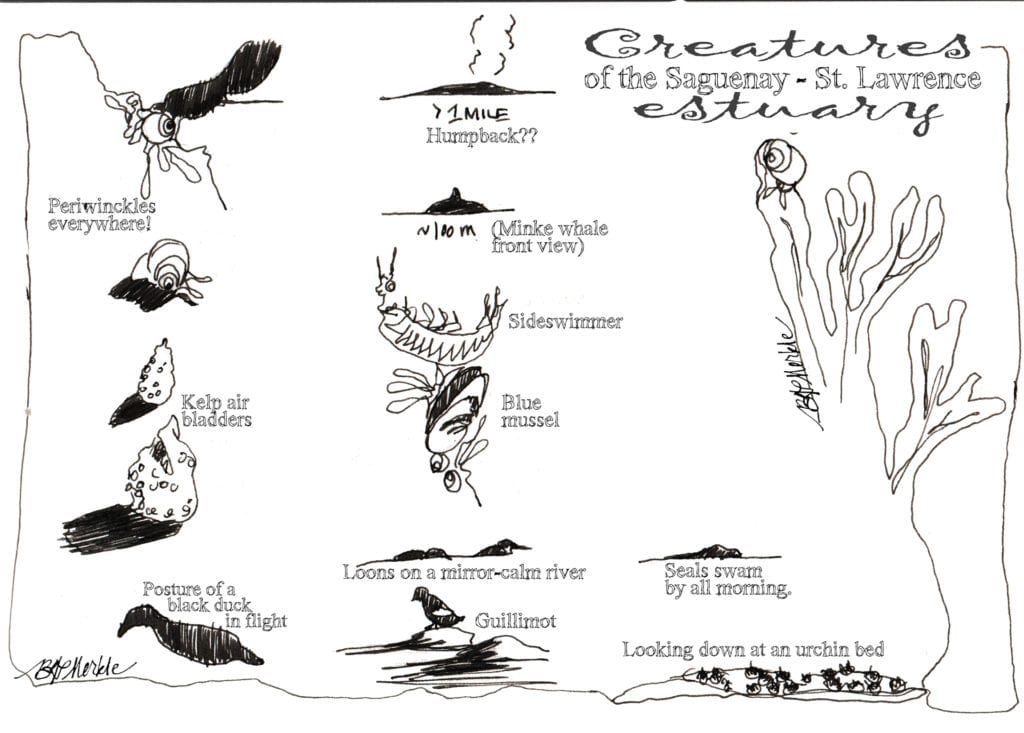

Bethann seamlessly blends art and science in her work with inspiration from notable polymaths and insights from research on creativity, which together advocate for drawing and storytelling as an effective way to learn about science and nature.

Bethann will select finalists for the People’s Choice category for the 2021 Visualizing Science Contest.

What drew you to the field of science communication?

I moved to Quebec City (from Montana) in 2010 with two stipulations on my work visa: nothing with children or food. Having spent the previous phase of my career in nonprofit management, urban sustainability, and conservation education, food and teaching children were core skills. So, I had to reconceptualize what I knew how to do and find a way to do that productively in a new-to-me language environment. I learned French as I transitioned into consulting on communications/nonprofit management. I also started doing freelance journalism and editing science manuscripts for ESL authors.

I learned a huge amount about science writing and editing in the trenches (and from Twitter and the National Association of Science Writing). I was a summer research assistant for my husband’s PhD research (bison in Prince Albert National Park) and tagged along to an Ecological Society of America conference, attending via my press credentials. At that meeting, I met a band of women who were top-notch ecologists also passionate about sharing science. We identified a need for more training (sharing our skillsets with others) within ecology, launched the Communication and Engagement Section of ESA (2014), and never looked back. Now, I realize I’ve done science communication since I first drew aquatic macroinvertebrates for a commission or leading and developing conservation education curricula as a first-gen undergrad. But, I didn’t know to call it that back then.

What is the first thing you recommend to researchers who want to be more creative with how they communicate their work?

Creativity can be practiced and enhanced. We know this from on-going research into how creativity rises in disciplines as seemingly disparate as music performance and theoretical physics. Such practice requires two things: (1) incubation time (time thinking/reflecting, not actively doing or producing) and (b) taking intellectual risks (often in the company of others; often without a concrete objective).

Second, cross-training is essential. Take Einstein for example—he is on record saying most of his major breakthroughs in physics were first conceptualized in musical terms, a process made possible because he was also an accomplished violinist. History is replete with examples of scientists (many Nobel Laureates) who were skilled enough in the arts or humanities that they could have quit their science day jobs and pursued careers as artists, poets, and musicians. Many saw no distinction between their disciplines and fed each with the other.

And third, few innovations happen overnight or solo. We have a counterproductive habit of hailing career-long developments (the lightbulb, telephone, precursors of the internet, penicillin) as a sort of alchemy that emerges from rare genius. But, geniuses are social constructions—their mythologies gloss over deep development of skill, connection of wide-ranging ideas, and rich networks of collaborators and supporters.

What do you think is the most important thing a researcher should consider when creating a scientific illustration?

Audience/stakeholders. Who are you trying to reach? Why? (And that why needs to be driven by what is in it for the viewer, not merely what the researcher thinks someone needs to know about the research.) In a nutshell, that’s what should drive every effort involving science communication, public engagement, community outreach, policy work, or whatever we want to call it. While there are certainly a wide array of graphic design or artistic considerations, no amount of beautiful art or accessible color palette and typeface discussion will salvage a visual communication effort that is developed in an echo chamber.

It is hard work to get this right, because it requires actually engaging with and understanding the values and needs of the target viewer, and many researchers work in academic or industry settings where the incentives and career benchmarks do not encourage authentic stakeholder engagement. But, our conditioning in science is to rely on, and layer on, more and more evidence (the deficit model). However, considerable evidence indicates that people are not persuaded by facts and numbers (but rather by social pressure, convenience, and personal experience). Science visuals must account for this reality just as any other effective science communication effort.

Sketchbook spread with marine wildlife made during a reporting trip in Quebec | Bethann Garramon Merkle