From geography to ecology to epidemiology to sociology and beyond, much of the data we generate has a spatial element – a physical location, distribution patterns, and geographical relationships with other data or variables, for example. The tool of choice for showing those elements? Maps.

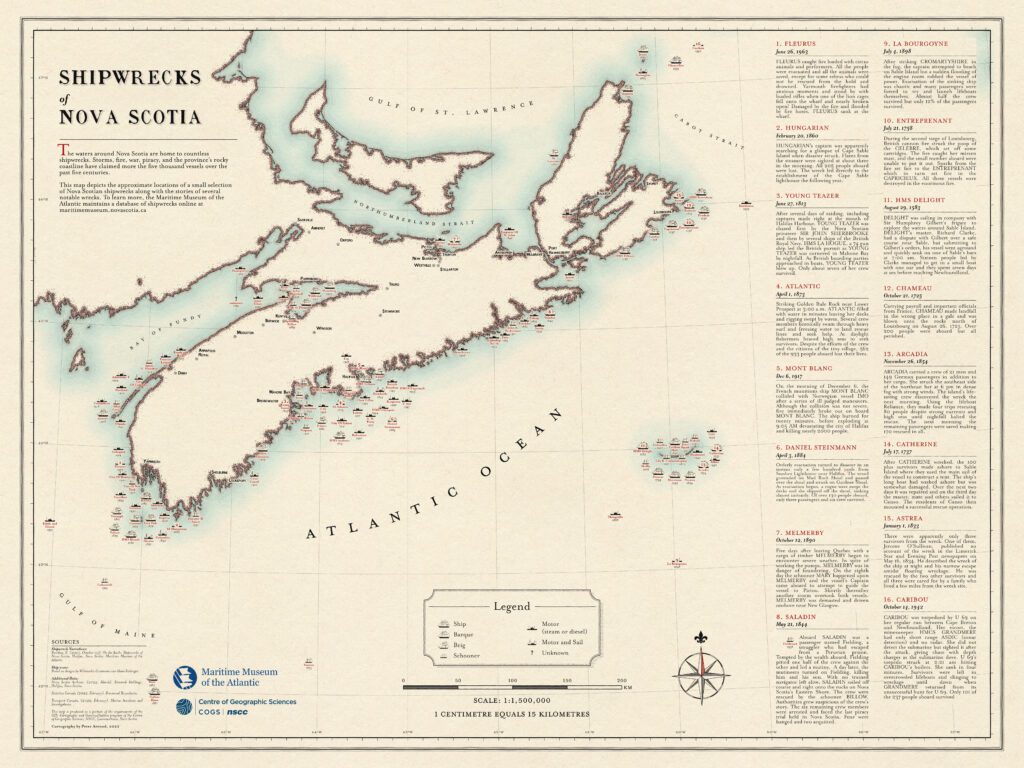

“Maps are an extremely useful tool,” says Thomas Herbreteau, Chair of the Canadian Cartographic Association’s Geovisualization and Map Design Special Interest Group. “They can be leveraged to improve your projects, our cities, and our society. They can save lives. They can also visualize a story like no other medium.”

We asked Herbreteau to share his top tips for not just making a good map to communicate your research, but for making a great map.