Dr. Ursula Franklin was many things: physicist, educator, feminist, holocaust survivor, and peace activist to name a few. To capture her life story in a blog post simply won’t do her justice, but I’m pleased to have the opportunity to write about this eminent physicist.

Ursula Franklin’s love for physics began early in her life, but under trying circumstances. Born into a Jewish family in 1921 in Germany meant that Franklin and her family faced countless trials and persecution leading up to and during World War II. In 1933, when Franklin was only 12, the Nazi government came into power and very quickly put into effect The Nuremberg Laws (in 1935) that stripped Jews of many rights and excluded them from normal life in Germany.

Ursula Franklin’s love for physics began early in her life, but under trying circumstances. Born into a Jewish family in 1921 in Germany meant that Franklin and her family faced countless trials and persecution leading up to and during World War II. In 1933, when Franklin was only 12, the Nazi government came into power and very quickly put into effect The Nuremberg Laws (in 1935) that stripped Jews of many rights and excluded them from normal life in Germany.

It was during this time that Franklin decided she would pursue the sciences.

She once said in an interview in The Atlantic: “When I was a child in school, the fact that the laws of nature seemed to be permanent and immutable, compared to the laws of the state, made science most attractive to me. And I recall as a kid in school, a physics experiment—and my almost mischievous pleasure that even these overwhelming, secular authorities couldn’t change the direction of a beam of electrons. And so I went into science for the fact that this was a career one could pursue with integrity—and that’s very dubious—but it’s what appears to the 13-, 14-year-old.”

Franklin began her undergraduate degree in 1940 in Berlin but was forced out of school during the final 18 months of the war and sent to a labour camp while both of her parents were sent to concentration camps. Miraculously, Franklin and her parents survived and were reunited when the war ended. At that time, Franklin returned to university to finish her PhD studies.

She was perseverant. During an interview with June Callwood, Franklin remarked, “There were so many people who perished. I didn’t.” She went on to say, “How does one conduct a responsible life that really has been given by an accident of history? It could just as well have been given to somebody else, but you have it, and you better do something.”

And so in 1948 she received her PhD in experimental physics from the Technical University of Berlin. At this point her interests had developed particularly in the field of solid-state physics—the study of hard matter that informs the creation of new materials and technologies such as the cell phone in your pocket. In her interview with The Atlantic she described her interest in structure not only applied to physics but also to politics and society. The idea that the properties of a whole are not simply the sum of its smaller parts but something immensely different fascinated her. She became passionate about combining science and society by promoting the use of science for the good of humanity.

With this passion in her heart and the physics degree in hand, she left Germany and moved to Canada in 1949 to begin a Lady Davis Post-Doctoral Fellowship at the University of Toronto. Following that, in 1952, she was offered a research position at the Ontario Research Foundation where she worked for 15 years. During this time, she pioneered the development of archaeometry, the field in which archaeological materials are dated using techniques such as radiocarbon analysis. She used this expertise in the early 1960s to study the levels of strontium-90 in baby teeth, a substance that was present in the fallout from the testing of nuclear weapons, with the intention of showing with scientific proof that it was in the U.S. government’s best interest to pause atmospheric nuclear weapons testing. She succeeded and the government stopped this testing.

In a conversation with Canadian Science Publishing, one of Franklin’s mentees, Dr. Mohammedmoin Sadeq, Associate Professor of History and Archaeology at Qatar University, said “Ursula was very enthusiastic about expressing her opinion against not only producing nuclear weapons but also testing them due to the massive negative health impacts on the human being and on the environment in general.”

She returned in 1967 to the University of Toronto to start a position as an Associate Professor in the Department of Metallurgy and Materials Science. In 1984 she became a full Professor, making her the first woman ever with this title at the University of Toronto.

When asked about this achievement in an interview for the University of Toronto in 2015, Franklin said, “I was very pleased about it. There is such a profound difference in being the first and being the only. If you are the only woman, people can treat you like an oddity; if you are the first, then it is quite different…being the first woman University Professor, I was really happy because it meant there would be others.”

Franklin was truly a pioneer of feminism during her time at the University of Toronto. She was part of the Voice of Women group, a Canadian anti-nuclear organization that encouraged women to work together for peace. She also gave many speeches and wrote articles about feminism that are now documented in The Ursula Franklin Reader, published in 2006.

In her interview for the University of Toronto, Franklin described the feeling of great joy at seeing young women receive more recognition and being offered positions that they deserved and could excel in. Being the first female Professor at the University of Toronto meant that she was an inspiration to many women whom she likely did not even know personally, but who knew of her success and drew courage from it.

Dr. Roberta Bondar for example, Canada’s first female astronaut, spoke on CBC Toronto’s Metro Morning radio show last year about the ways in which she felt inspired by Franklin. Bondar completed her PhD at the University of Toronto in the 1970s and commented on the empowerment she felt from knowing that women like Ursula Franklin were on campus, even though she never personally met Franklin until much later after her degree.

Bondar also talked of the way people perceived Franklin’s charm which came from the marriage of her passions. Though she was immensely successful in her scientific career, she was equally dedicated to peace activism and feminism.

During the rest of her career, Ursula Franklin received many prestigious awards and was appointed to the Order of Ontario, honoured as a companion of the Order of Canada, inducted into the Canadian Science and Engineering Hall of Fame, and presented with over two dozen honorary degrees.

In July of last year Ursula Franklin died at the age of 94, leaving behind a tremendous legacy and an immeasurable influence. She extended her role of scientist to help build more informed, inspired, and peaceful communities, and this will not soon be forgotten.

—

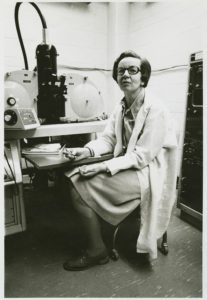

In-text image: The University of Toronto Archives, Ursula Franklin, Professor of Materials Science, A2012-0009/009 (55)