For the first time, researchers have conducted a long-term study documenting the colonization of zebra mussels (Dreissena polymorpha) in a small river system. Researchers from the Canadian Museum of Nature sampled stretches along the iconic Rideau River for over a quarter century to reveal the invasion history in one of Ottawa’s defining landmarks and a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

“What we saw below the surface was just stunning,” said André Martel, one of the lead authors of the study that SCUBA dived in the river. “The progression has been just incredible in terms of biomass of zebra mussels per square meter, increasing in just a few years.”

Zebra mussels clinging to the floor of a lock at Burritts Rapids, Ontario. (Photo | Museum of Nature)

Many residents of Ontario and Quebec have made previous acquaintances with zebra mussels when going for a lakeside dip and emerging from the water with bloodied toes. Zebra mussels cling to the mossy surfaces of rocks and often lacerate the feet of unsuspecting swimmers.

In addition to being a nuisance for summertime cottage dwellers, zebra mussels can have devastating environmental impacts. Their invasion can smother out native species and has led to local extinctions, and their presence can have cascading effects on freshwater ecology.

“What you have is millions of filter-feeding machines extracting all the good plankton, the good diatoms, the good unicellular plants,” said Martel. Zebra mussel colonization may lead to clearer waters, but that can then increase the growth of macrophytes or underwater plants. These macrophytes can then die en masse, leading to lake fouling.

Brought over from Europe in ship ballast waters, zebra mussels were first reported in Canada in 1986 in the Great Lakes. The mussels then spread quickly throughout Ontario and Quebec and have moved as far west as Lake Winnipeg in Manitoba. They were first spotted in the Rideau River system in 1990 on a large steel boat.

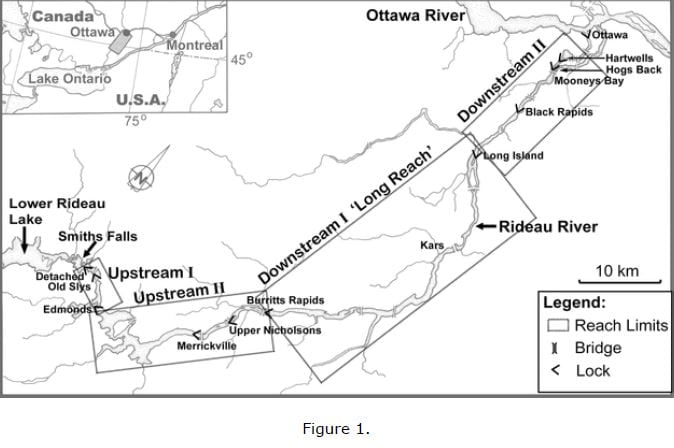

Sampling began in the Rideau River in 1993. A team of researchers, students, and volunteers measured densities per square meter at 13 different locations along the 100 km river, divided into four stretches: Upstream I, Upstream II, Downstream I, and Downstream II.

Map of the Rideau River-Rideau Canal system showing 13 sampling sites where the

zebra mussel (Dreissena polymorpha) was studied during 1990-2015.

Martel described the blitzkrieg downstream zebra mussel colonization as “stunning.”

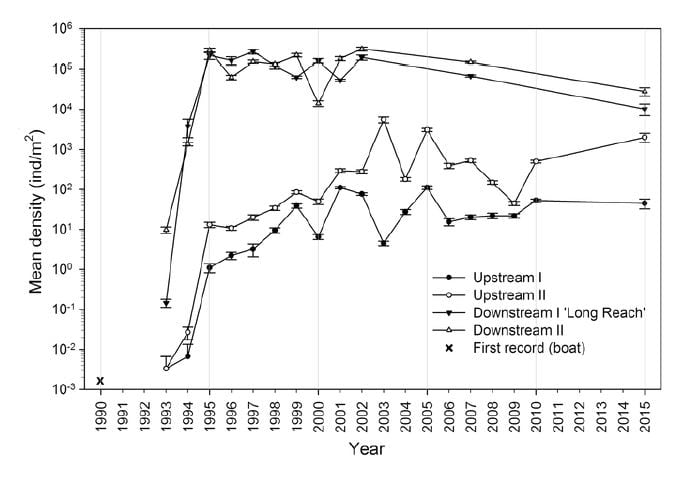

At Mooney’s Bay, an area close to central Ottawa, the average zebra mussel density was 2 per square meter in 1993. By 1995, this had exploded to a density of 296,374. Nearby, Hog’s Back had a similar increase, starting with 4 mussels per square meter in 1993, which grew to 460,960 in 1995. “There was an exponential growth beyond what I would have anticipated,” said Martel. “It was about a 10,000–100,000-fold increase.”

Mean annual density of zebra mussels (Dreissena polymorpha) (mussels per m2)

calculated for four reaches of the Rideau River shown from 1993 to 2015.

Over the 26 years the researchers also found a strong upstream–downstream pattern in which the lower reaches of the river had significantly higher densities than the start of the river near the community of Smiths Falls, Ontario. This result wasn’t entirely surprising, since the current upstream was more rapid and turbulent, while the lower sections of the river widen and have a slower current, more similar to a lake. These calmer conditions give zebra mussel larvae the opportunity to settle and colonize. The upstream–downstream pattern supports the idea that slow-moving, lake-like sections of rivers are important sources for zebra mussel recruitment downstream.

“We had hoped that upstream the impact was going to be very minimal. Unfortunately, that wasn’t so,” said Martel. Despite colonization upstream being much slower, it was still enough to cause a significant environmental impact. By 2015 some sampling sites in the “Upstream II” reaches of the river had reached densities of nearly 2000 zebra mussels per square metre.

“There’s nothing you can do to get it out, just a natural disease or virus or some sort. It’s there to stay, and it’s been like this for over 30 years in the Great Lakes,” said Martel. The researchers worry that the invasive molluscs will spread to the St. John River system, a gateway to the Maritimes and recommended boat owners to clean zebra mussels and debris from their vessels and trailers and drain all bilge water when trailering to prevent any further spread of zebra mussels.

In a future study Martel plans on examining the effects of colonization on native mussel species in the upper reaches of the river, and their current research is being incorporated into a large-scale review of zebra mussel colonization from around the world.

- A native mussel called the Giant Floater on its last leg as the smaller zebra mussels have attached to its shell, preventing it from opening, from normal filter feeding, and from reproducing normally. (Photo | André Martel, Museum of Nature)

- In the fall of 2010, two volunteers count zebra mussels in quadrats (each 0.5 by 0.5m) on the floor of lock 31, at Smiths Falls, Ontario. (Photo | Museum of Nature)

- Jacqueline Madill scraping zebra mussels from a 5 cm by 5 cm quadrat into a small ziplock back at Hog’s Back Falls in Ottawa. (Photo | Museum of Nature)

Read the full paper: Twenty-six years (1990–2015) of monitoring annual recruitment of the invasive zebra mussel (Dreissena polymorpha) in the Rideau River, a small river system in Eastern Ontario, Canada in the Canadian Journal of Zoology.