Northeastern Alberta is a tough place to work. Bitterly cold, dark winters illuminated only by an occasional flash of northern lights. In the summer, fallen trees block trails, and bears wreak havoc on any equipment left unattended. And, of course, there are the biting flies.

But there’s no better place than Wood Buffalo National Park for studying the ecology of its eponymous residents.

“To eat food and/or to be food are the factors typically examined,” says Rob Belanger, lead author in a new paper in the Canadian Journal of Zoology. Belanger, now a resource ecologist for Parks Canada, studied wood bison habitat selection as a graduate student at the University of Alberta.

It seems logical that animals would like places with lots of food and few predators. However, earlier work on bison showed that they avoided food-rich areas, like marshes, during the summer months compared to the winter.

“I wanted to examine why bison might be avoiding these forage-rich areas.”

Belanger focused on two common summertime nuisances for bison—harassment by biting flies and soft footing, which can stop burly bison from making a quick getaway.

Rather than approach a 1,200 kg species at risk and solicit its opinions about Albertan real estate, Belanger and his field assistant, Melissa Dergousoff, systematically scoured their field sites—in both the winter and summer—for bison dung, a sure-fire indicator that the animals had passed through the area.

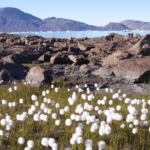

They also recorded the amount of forage (grass) and biting flies as well as soil moisture across four key bison habitats—deciduous forest, marsh, pine forest, and esker, a natural ridge made of gravel or sand.

Back in the lab, and presumably after a long shower, the team crunched the numbers.

“During summer, bison avoid forage rich areas because these areas have great amounts of biting flies and softer footing,” suggests Belanger. The flies are irritating, and the soft ground makes it hard to move around.

Instead of slogging through fly-infested marshes, bison spend their time around eskers, where the prevailing winds keep bugs away. The abundant forage across all habitats affords bison the luxury of being choosy about where they spend their summers.

“During winter, when flies are absent and soils frozen, the distribution of forage significantly influenced selection, with bison selecting areas of dense grasses.”

Bison wait out the worst of the Canadian winter in places where they can find enough to eat, like marshes. At least the cold weather means the flies are gone, and the mud is frozen solid.

All together, Belanger’s work demonstrates that habitat selection is a lot more than finding food and dodging wolves. Bison also avoid irritating neighbours and getting stuck in the mud.

Like their more famous relatives, the plains bison, wood bison were nearly eradicated by hunting in the early 1900s. Careful management allowed the population to grow from a low of 200 individuals in 1957 to a self-sustaining herd of about 3,000 today.

Understanding what kinds of habitats wood bison prefer, and why, is key to conservation of the species.

Read the paper: Evaluating trade-offs between forage, biting flies, and footing on habitat selection by wood bison (Bison bison athabascae) in the Canadian Journal of Zoology.

*Banner image: Wood bison bull | Rob Belanger