Foraging humpback whales are known for incredible above-water theatrics and long sub-surface dives. But how do we know exactly what they’re eating when they do most of their feeding during their long disappearances underwater? Since the 1990s, Dr. Rhonda Reidy has observed the rapid appearance of humpback whales in B.C., for which reliable diet data is unavailable. For her graduate studies, she was drawn to the University of Victoria’s strategic concentration in ocean science and community-based coastal research, particularly the labs of Dr. Francis Juanes and Dr. Laura Cowen, for their collective expertise in fisheries ecology, underwater soundscape ecology, and biostatistics.

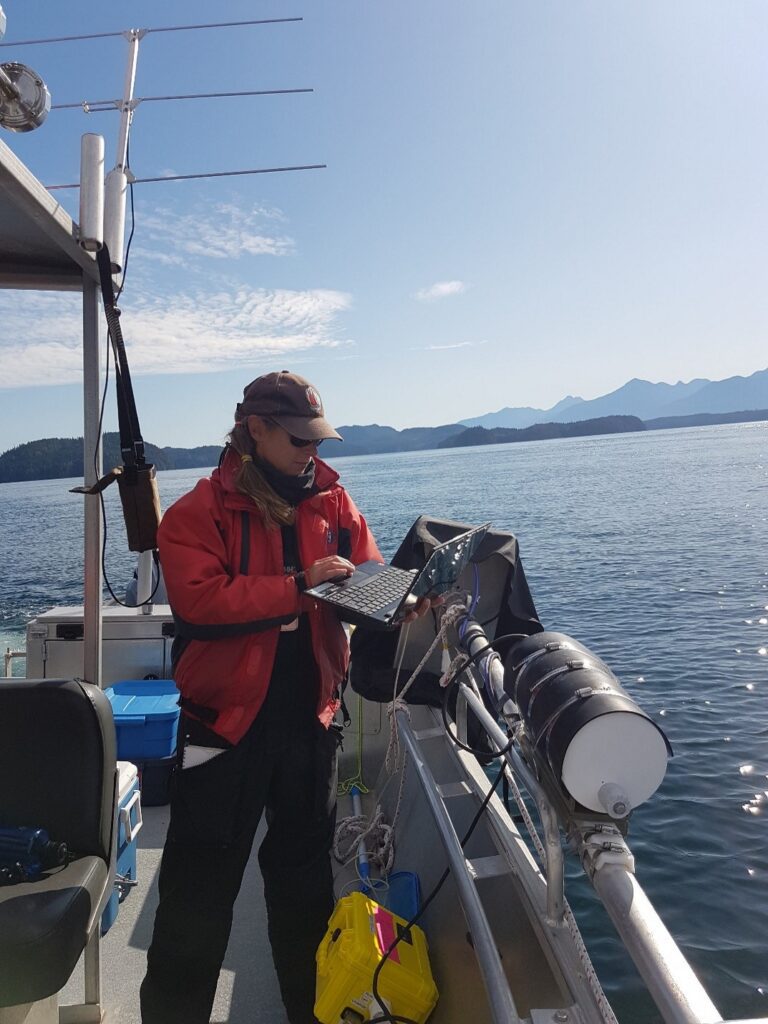

Now a postdoctoral researcher with Environment and Climate Change Canada, Dr. Reidy’s PhD research focused on the foraging ecology of humpback whales off southern and northern Vancouver Island, B.C., which differ in their feeding behaviour; “Critical information about humpback whale prey fields is missing in B.C. because it is extremely challenging to study”, Dr. Reidy explains. Her work is starting to fill in these gaps, using a variety of innovative tools. From pool skimmers and Ziploc bags to sophisticated instruments that dive with the whales, a whale researcher’s toolkit has it all.