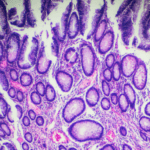

What if the key to preventing chronic disease wasn’t a miracle drug or a groundbreaking surgery but the choices we make every day—what we eat, how we sleep, and how we move? While we often think of nutrition as a simple input-output equation, nutrition scientist Dr. Scott Harding likens it to a tapestry of interactions: our small choices, all enmeshed, create the fabric of our health. But how do these threads connect? And what happens when they start to fray?

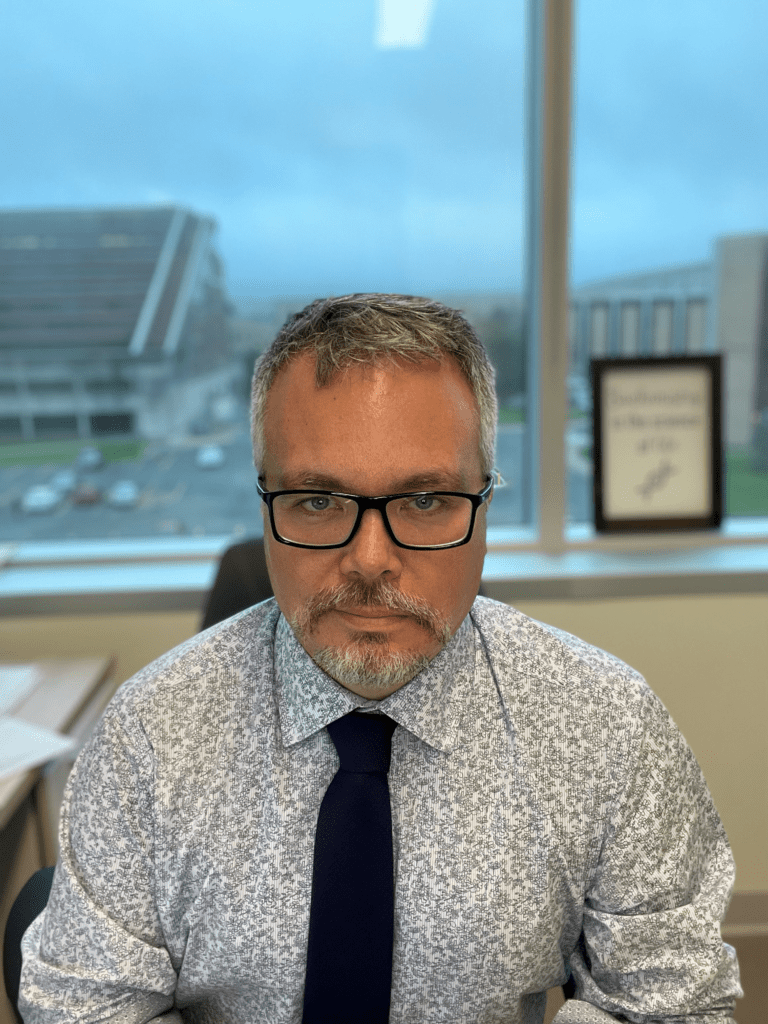

Dr. Harding, the new co-Editor-in-Chief of Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism, and a leader in cardiometabolic research, is on a mission to understand just that. With a focus on glucose metabolism, cholesterol biochemistry, and lifestyle factors like sleep and diet, his work provides a holistic view of health and reveals how subtle adjustments—like adding omega-3 fats to your diet or improving your sleep quality—can transform long-term outcomes. “Chronic diseases don’t develop overnight,” Harding explains. “They’re built over decades of seemingly insignificant choices.”

Dr. Harding, the new co-Editor-in-Chief of Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism, and a leader in cardiometabolic research, is on a mission to understand just that. With a focus on glucose metabolism, cholesterol biochemistry, and lifestyle factors like sleep and diet, his work provides a holistic view of health and reveals how subtle adjustments—like adding omega-3 fats to your diet or improving your sleep quality—can transform long-term outcomes. “Chronic diseases don’t develop overnight,” Harding explains. “They’re built over decades of seemingly insignificant choices.”

Our current choices aren’t doing us many favours. Chronic diseases—such as heart disease, diabetes, and even certain cancers—are rising worldwide and affecting younger people, fueled by poor diets and sedentary lifestyles. Public health policies, like Newfoundland and Labrador’s recent sugar-sweetened beverage tax, aim to tackle these issues, but their success depends on understanding the science behind behaviour change.

Of course, challenges abound. Misinformation about fats, for instance, continues to confuse the public about what’s truly healthy. And how do you convince people to rethink their habits when change feels overwhelming? Through his lab’s work on omega-3s, sleep disruption, and even sea urchins, Dr. Harding demonstrates the power of creative, evidence-based solutions to these complex problems.

In the interview below, Dr. Harding shares how his career journey—from studying the cholesterol-lowering effects of oats on BBC’s Trust Me, I’m a Doctor to exploring the therapeutic potential of sea urchin waste—has shaped his approach to research, public health, and communication. He offers insights into the intersection of science, policy, and outreach, encouraging young researchers to step into the spotlight and make their voices heard.

Ready to hear more? Dive into our Q&A with Dr. Scott Harding to explore the science behind nutrition, the nuances of metabolic health, and how we can all weave healthier habits into our lives.