With the open science movement now sweeping across disciplines, researchers are increasingly creating findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable (FAIR) datasets.

One way data are made discoverable for reuse is with data papers—a thorough description of a dataset(s) deposited in a publicly accessible repository.

Unlike traditional peer-reviewed papers, which focus on original research, data papers undertake no analysis or interpretation. “Data papers are essentially a means of taking detailed stock, or inventory, of data,” explain Drs. Lisa Loseto and Melissa Lafrenière, Editors-in-Chief at Arctic Science, an open access peer-reviewed journal that accepts data papers.

What can data papers do for science?

1. Data papers support scientific discovery

Opportunities to build on existing data multiply “[a]nytime people decide to archive their data and take the time to explain what the data [are],” says Dr. Janet Prevéy, an ecologist with the U.S. Geological Survey and lead author of Arctic Science‘s inaugural data paper The tundra phenology database: more than two decades of tundra phenology responses to climate change.

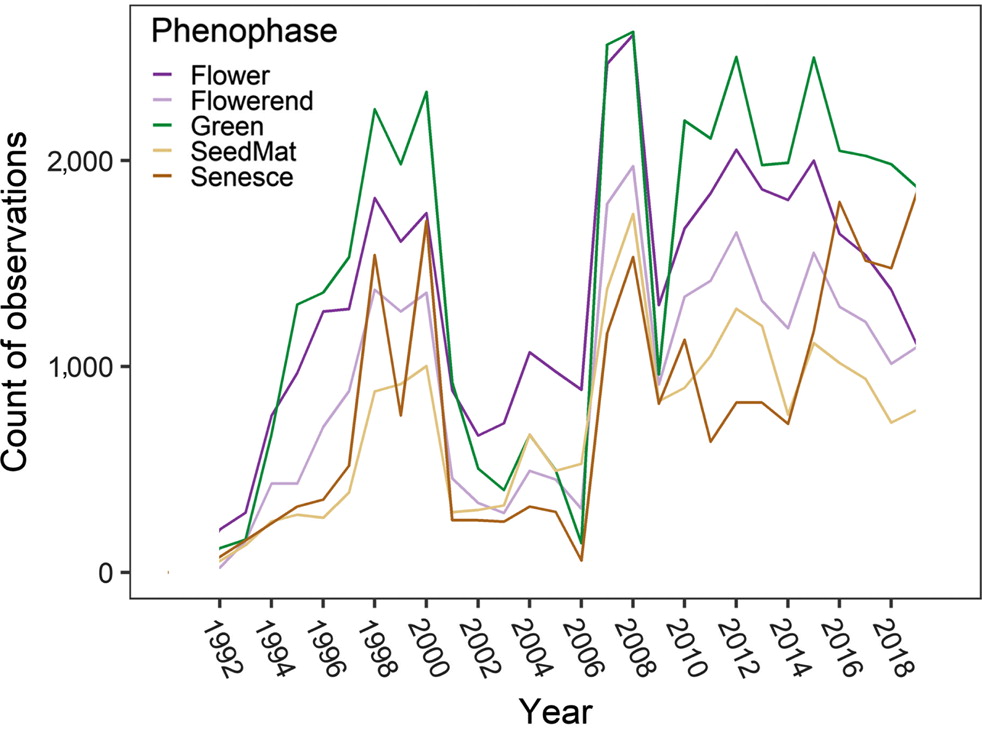

The paper describes plant phenology data collected under the International Tundra Experiment (ITEX). At the time of the paper’s publication, the database contained more than 150,000 observations made by multiple different researchers dating back to 1992, and covered some 278 plant species.

Per year, the total number of phenology observations of each phenophase type across all study areas in the tundra phenology database | Learn more

The phenology database is housed on the online and open-access Polar Data Catalogue. This open nature is a critical component of a data paper. Data collection is a monumental effort. And when the dataset itself is misplaced or not accessible, and consequently underused, “it is a huge loss to science” notes Dr. Heather Lynch, professor of ecology and evolution at Stony Brook University.

Lynch has produced several data papers over the years, including a description of the Mapping Application for Penguin Populations and Projected Dynamics (MAPPPD), an online database which builds on another of Lynch’s data papers describing survey data on breeding birds in the Antarctic.

2. Data papers are collaborative initiatives

“Data papers are most useful when you are in a situation where you have multiple different datasets from a large number of researchers and groups, like with the ITEX network,” says Dr. Ingibjörg Svala Jónsdóttir, professor of ecology at the University of Iceland, member of the Arctic Science editorial board, and co-author of the phenology data paper.

Creating the database requires substantial work. “Everyone has different hypotheses and experimental setups, so people collect data slightly differently at all of their sites,” Prevéy explains. Prevéy and the team had to collect, validate, clean, and organize the data in the same format so observations could be compared and used together. “This was one of those really successful collaborative efforts.”