(A continuación, el blog en español)

Shark spotting is no easy task. Even the most eagle-eyed boater needs to be lucky enough to come across them.

Drones are already used to find other marine animals, typically surface breathers like whales or those living in clear waters, which allows drone cameras to see beneath the sea surface.

However, as Martin Benavides, a PhD student at the University of North Carolina’s Institute of Marine Sciences, points out, sharks don’t need air. Some sharks also live in rather turbid waters.

Thankfully Benavides’ new study, published in the Journal of Unmanned Vehicle Systems, offers some hope for murky-water shark researchers; mid-day sunshine and little wind doesn’t only make for pleasant weather—it may also be better for drone-based shark photography.

Benavides’ study focused on bonnethead sharks that frequent North Carolina’s estuaries; they are easily identifiable from their scallop-shaped head.

Over multiple days, Benavides flew a fixed-wing drone equipped with cameras over the Newport River Estuary.

Thirty drone flights later, a team of volunteers were tasked with spotting sharks in the photos Benavides captured with the drone. Rather than search for real sharks, Benavides had the shark spotters look for decoys of bonnetheads and the more generic-looking Atlantic sharpnose shark that he planted in the estuary.

By knowing where the decoys were and the conditions on the day of the flight, Benavides was able to calculate when the shark spotters were best able to find and correctly identify bonnetheads.

Although drones can be easily purchased, decoys cannot. While considering how to fashion realistic decoys, an unusual opportunity emerged. The aquarium that funded Benavides’ work had to perform a necropsy on a bonnethead; “We asked if we could trace the shark,” Benavides said. “I put the shark on top of a big piece of paper and traced around the outline [of the shark]… cut out the outline, and then traced the shape onto wood and cut it out,” noting that it was also a rather smelly affair.

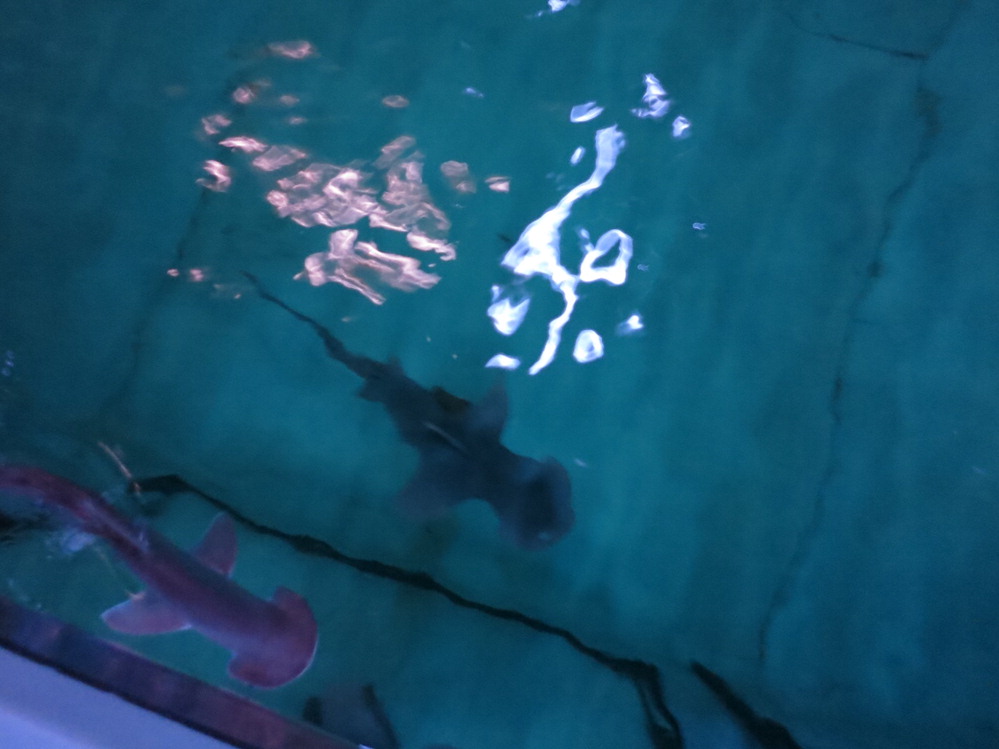

Live bonnethead (bottom left corner) and bonnethead decoy (slightly off-center).

Benavides found the likelihood of shark spotters seeing a decoy increased when the decoys were in shallow depths (generally less than 0.7 m), on days with low wind speed and little to no cloud cover, and from photos taken around midday.

The latter condition came as a surprise because that’s when the sun is highest in the sky; “If we have the sun overhead and we’re taking pictures overhead, we’re going to get glare off of the water that could block detection,” Benavides explained.

As it turns out, “it’s better to have more light penetrating the water column then to be worried about glare”. When the volunteers found a decoy, they were largely successful at being able to tell if it was a bonnethead or not, regardless of conditions.

Benavides still encourages researchers to consider their own local conditions before embarking on drone-based surveys. For example, turbidity, which influences the maximum depth at which sharks can be spotted, changes seasonally with tides and with location even within a single estuarine system.

“We have to test the technology out in different habitats, different environments, and really start to understand where we can and make conclusions [on how efficient drones are for shark detection studies].”

Read the paper: Shark detection probability from aerial drone surveys within a temperate estuary in the Journal of Unmanned Vehicle Systems.

*Banner image: Drone photograph of estuary | Martin Benavides

*Translation provided by Martin Benavides