Dr. Anderson has collaborated with scientists at the NASA Ames Research Centre and her research “has taken [her] to 5000 m.a.s.l. in the Nepalese Himalaya, to the alpine meadows of Monte Bondone in Italy, the Majadas in Spain, the desolate peatlands of Exmoor, and the beautiful coastline of Cornwall.”

And in the remote sense (pun intended) to Canada as co-Editor-in-Chief at Drone Systems and Applications, published by us—Canadian Science Publishing.

Please join us in welcoming Dr. Anderson and get to know her in this Q&A.

1. We stopped ourselves from Googling “what is remote sensing”? How do you explain this concept to the students you teach?

Remote sensing is an amazing interdisciplinary subject which requires engagement with a wide range of subjects from physics (i.e. understanding measurement of light), to computing (i.e. extracting information from the data) and finally to the environmental science applications that use it. I love that intersection between the pure sciences and more applied aspects.

2. What first inspired you to learn remote sensing?

I first learned what remote sensing is at university and was lucky to be taught by an incredible scientist, Prof. Ted Milton at [the University of] Southampton in the UK. He really inspired me to develop my curiosity for the subject and I ended up studying for my PhD under his supervision. I really attribute my love of the subject to his brilliant teaching—and I still use the techniques I learned from him in my everyday job. The photograph below shows me using one of his handheld ‘Milton Multiband Radiometers’ on a recent fieldtrip to Nepal for measuring the reflectance of plants in visible and near infra-red regions of the spectrum.

The “Milton Multiband Radiometer” at work in Nepal | Karen Anderson

3. What is something often misunderstood about remote sensing?

Most of the time, remote sensing systems are measuring indirect proxies for the parameters that scientists are really interested in. [For example,] canopy chlorophyll concentration is inferred from a measurement of reflectance, or tree height is determined using a precisely timed laser pulse. Relating the desired parameters to the remotely sensed measurements relies on careful calibration and validation and often, just as much time (sometimes more time) is spent on the ground gathering measurements to compare to the remote sensing data, as is spent at the computer looking at image data.

4. What is your favourite application of remote sensing?

The thing I always love to teach is optical/infra-red remote sensing of vegetation. I find it amazing that we can see the impacts of sub-cellular chemicals and leaf structures in a vegetation spectrum. It never gets old!

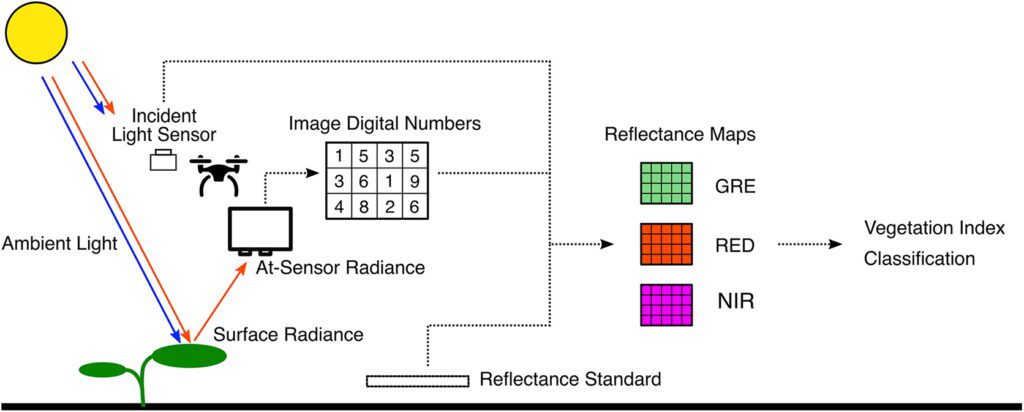

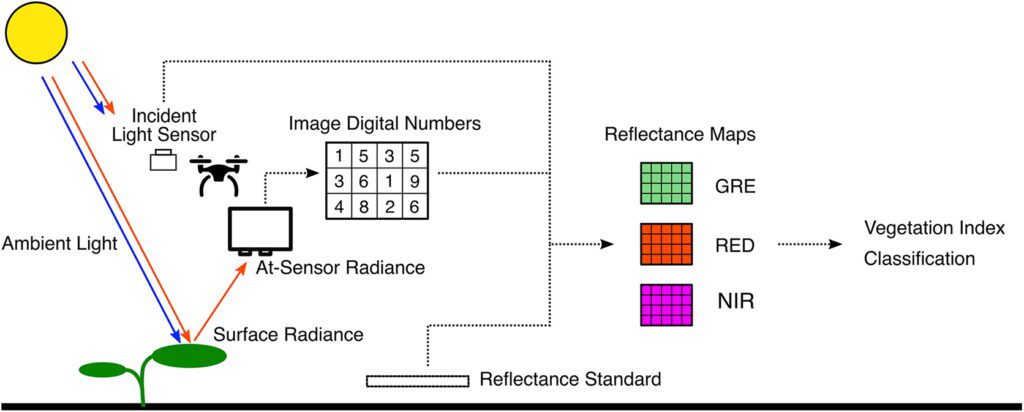

Multispectral drones can sense information from surface radiance to reflectance maps, enabling further calculation and classification | Assmann et al. https://doi.org/10.1139/juvs-2018-0018

5. In 2013 you published on how lightweight UAVs would “revolutionize spatial ecology”. Nearly a decade later, how has the field of spatial ecology advanced because of UAVs?

When we wrote that paper, the field of digital photogrammetry was just starting to be tested by ecologists. It’s been amazing to see how that’s developed over the past decade—we now know that it is possible to use structure-from-motion photogrammetry to measure the shape and size of desert plants, submerged corals, and even animals! This means that non-destructive sampling of species allometry can be undertaken using overlapping photographs captured from a drone. I think that’s a big step forward.

6. What’s been the most unexpected development of UAVs in the last decade?

From a user perspective—and perhaps this is not ‘unexpected’ but it’s certainly helpful—it is that the systems have evolved from ‘build-your-own’ to out-of-the-box ready-to-fly systems. Ten years ago we were soldering wires into autopilots and using piano wires to buffer vibrations between drones and camera mounts. Now, we can open a box and be in the air within five minutes. Surveys just got way easier as a result of that. The second thing that is unrecognizable now compared to ten years ago is battery technology. Smart batteries make the flying experience less stressful and more predictable.

7. Your lab’s long-term monitoring of peatlands in Exmoor National Park is helping inform restoration practices. How else are UAVs helping communities and countries achieve sustainability goals?

It’s been really good to track the restoration efforts from above using our drones on Exmoor. I think elsewhere, drones are a really flexible tool for conservation—they can provide video footage to highlight the plight of an area or species, they can be used in active protection of lands, and they are being put to great use in understanding the behavior of at-risk species like orangutans. I think the work done by people like Serge Wich and Lian Pin Koh at Conservation Drones is really amazing in this regard.

We are thrilled to introduce you to Dr. Karen Anderson, co-Editor-in-Chief at Drone Systems and Applications, an open access journal for developments in unoccupied vehicle systems.

We are thrilled to introduce you to Dr. Karen Anderson, co-Editor-in-Chief at Drone Systems and Applications, an open access journal for developments in unoccupied vehicle systems.