Have you ever found yourself wishing you could make an impact on how scientific discoveries and innovations are ultimately used?

Or be in the room when governments are reviewing policy to help make sure decisions are based on the best available evidence?

If this sort of applied science communication appeals to you, a career in policy advising is worth considering.

Science policy advisors act as liaisons between researchers and those who make policy, helping them to understand complex scientific findings quickly and having the salient points at hand when making decisions based on evidence. Policy advisors work both inside government and through extra-governmental organizations.

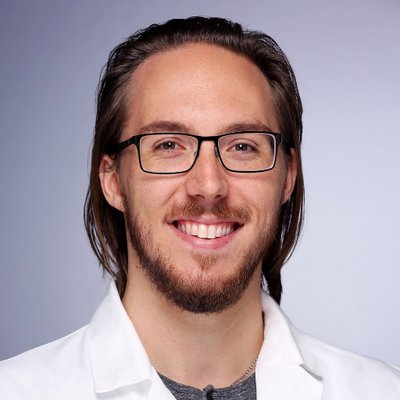

To better understand what it is to be a science policy advisor in Canada, I spoke with Dr. Kimberly Girling, the Research and Policy Director with the non-profit organization Evidence for Democracy (E4D), which promotes the transparent use of evidence in government decisions, and Dr. Shawn McGuirk, Senior Policy Advisor for the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC). Both are former STEM graduates who earned their PhDs in neuroscience and biochemistry, respectively.